“(He) was most emphatic in his conviction – the conviction of personal experience, that Sherman’s verdict, ‘War is Hell’ is the nearest thing to an adequate characterization of it that can happen.”

“‘In all reverence, War is hell – nothing else, and no effort to prevent war can be too assiduous or too costly. The supreme effort of every people should be not to get out of war, but to keep out; – not to win a war, but to prevent it.’” (Spalding, The Garden Island, June 1, 1920)

Colonel Zephaniah (Zeph) Swift Spalding fought in the US Civil War. “The Colonel was in command of the famous Seventh New York Regiment, which was the second to reach Washington, even before the regular mobilization of the union troops. … “

“They found that Washington was practically a Southern city in sentiment and population – there were more Southerners than Union men there…” (The Garden Island, June 1, 1920)

Spalding first enlisted in the 7th New York City Regiment. Within forty days, he had received a commission as a major in the 27th Ohio Regiment and held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in that regiment at conclusion of that war.

It was reported that, because of his service record with the 27th Ohio during that war, he gained the favor and recommendation of Ohio Governor, David Todd, and, in 1867 was appointed by President Andrew Johnson to serve as American Consul to the Kingdom Hawaiʻi in Honolulu.

Spalding, born at Warren, Ohio, near Akron, September 2, 1837, was son of Rufus Paine Spalding – Representative and Speaker of the House of the Ohio Legislature, Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of Ohio and member of the US Congress. Spalding was named after his father’s mentor, Zephaniah Swift, Chief Justice of Connecticut, whose daughter, Lucretia, was Zeph’s mother.

Shortly after the war, Zeph was tasked by Secretary of State William H Seward to serve as a ‘secret agent’ in Hawaiʻi (December 1867) to gauge “what effect the reciprocity treaty would have on future relations of the United States and Hawaiʻi.” (They were weighing reciprocity versus annexation.)

His mission was said to have been known only to his father, Congressman RP Spalding, to Secretary Seward and to Senator Grimes of Iowa. His reports were made in the form of letters to his father, who delivered them to Seward.

Spalding was strongly opposed to the reciprocity treaty, and was in favor of annexation, which he thought would be hastened by rejection of the treaty. (Kuykendall) That treaty, under consideration over 3-years (1867-1870) failed to pass.

On July 25, 1868 Andrew Johnson in a message to the US Senate nominated “Zephaniah S. Spalding, of Ohio, to be consul of the United States at Honolulu, in place of Morgan L. Smith, resigned.” (US Senate Journal) He served as such until June 1, 1869, when President Ulysses S Grant suspended Spalding and nominated Thomas Adamson, Jr to replace him.

Soon after leaving the consulate in Honolulu, Spalding associated himself with Kamehameha V, Minister Hutchison and Captain James Makee in a sugar venture on the island of Maui.

Spalding’s association and work with the West Maui Sugar Association apparently caused a personal change of heart, transforming him into a strong supporter of reciprocity, and, in 1870, he wrote to President Grant suggesting …”

“… ‘to admit duty free Sugar’ and other articles from Hawaiʻi, in exchange that the Hawaiian Government grant or lease “sufficient land and water privileges upon the Island of Oahu near the port of Honolulu … to establish a Naval Depot”. (Papers of Ulysses S Grant, September 27, 1870)

On July 18, 1871, Spalding married Wilhelmina Harris Makee, first-born daughter of Captain James Makee, at McKee’s Rose Ranch in Ulupalakua, Maui. In that same year, Makee’s eldest son, Parker, took over management of the West Maui Sugar Association.

Zephaniah and Wilhelmina had five children: Catharine “Kitty” Lucretia Spalding; Rufus Paine Spalding; Julia “Dudu” Makee Spalding; Alice “Flibby” Makee Spalding and James “Jimmy” Makee Spalding.

The Treaty of Reciprocity finally passed in 1875, eliminating the major trade barrier to Hawai‘i’s closest and major market. The US negotiated an amendment to the Treaty of Reciprocity in 1887 giving the US exclusive right to establish and maintain a coaling and repair station at Pearl Harbor.

In 1876, Captain Makee and Col. ZS Spalding purchased Ernest Krull’s cattle ranch in Kapaʻa, intending to start a sugar plantation and mill. After a brief stay in San Francisco (1875-1878) Spalding returned to the Islands, living on Kauai. Where Makee was already operating the Makee Sugar Company and mill at Kapaʻa.

King Kalākaua and others formed a hui (partnership) to raise cane. About the first of August, 1877, members of Hui Kawaihau moved to Kauai. Makee had an agreement to grind their cane.

Upon Makee’s death in 1879, Spalding took over management of the new sugar venture. Spalding also started the neighboring Keālia Sugar Plantation, in which King Kalākaua had a 25% interest. The Kapaʻa mill was closed in 1884, and all processing was done at Keālia. (In 1916, Colonel Spalding sold a majority of his holdings to the Līhuʻe Plantation Company, which kept the Keālia mill in operation until 1934, when it was dismantled and sent by rail to Lihue to become Mill “B”.)

In the 1880s, Spalding built the “Valley House,” a Victorian-style wooden mansion, one of the finest on the island.

From 1877 to 1881, Hui Kawaihau was one of the leading entities on the eastern side of the Island of Kauaʻi, growing sugar at Kapahi, on the plateau lands above Kapaʻa. (In 1916, Colonel Spalding sold his holdings to the Līhuʻe Plantation Company.)

On October 30, 1889, having traveled to Paris as the appointed representative of the Hawaiian Government, Spalding was presented the French order and ribbon of the Legion of Honor (Chevalier) during 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris.

Prior to the turn of the 19th century, Spalding had already developed a unique diffusion process for the refining of sugar at the Keālia Mill and was processing 24-hours a day. In 1900, with the construction of a new mill from Australia, sugar production was greatly increased.

Spalding expanded his business interests in Hawaiʻi, US and Europe. In 1895, the idea of a Pacific communication cable caught his interest.

He formed the Pacific Cable Company of New Jersey and on August 12, 1895, he entered into agreement with the Republic of Hawaiʻi “to construct or land upon the shores of the Hawaiian group a submarine electric telegraph cable or cables to or from any point or points on the North American Continent or any island or islands contiguous thereto.” (Congressional Record)

However, a rival company, Pacific Cable Company of New York formed to compete with him. Congress split its support, the Senate favored Spalding and the House favored his rival. In the end the two projects killed each other off. (Pletcher)

“I tried to bring it about some years ago. We had a concession from the Hawaiian Government which we proposed to turn over to any company that might be formed under the auspices of the United States, but we could not get the aid of the United States in building the cable, and, of course, there was not enough business to attempt it without that.” (Congressional Record)

(Ultimately, in 1902, the first submarine cable across the Pacific was completed (landing in Waikīkī at Sans Souci Beach; the first telegraph message carried on the system was sent from Hawaiʻi and received by President Teddy Roosevelt on January 2, 1903 (that day was declared “Cable Day in Hawaiʻi.”))

Spalding expanded his business interests in Hawaiʻi, US and Europe. During part of this time, Spalding moved his family to Europe to provide his children with a European education and Wilhelmina, “an accomplished musician,” who had suffered a debilitating stroke, with access to “concerts, opera and other musical events.” (Diffley)

In 1924, due to his failing health, Spalding left Kauai for California, to live with his son, James Makee Spalding, in the family home on Grand Avenue in Pasadena. The last few years of his life were spent in California due to failing health, and he died in Pasadena on June 19, 1927 at the age of 89.

On the afternoon of April 20, 1930, a monument was dedicated to Col ZS Spalding, built by his Keālia Japanese friends. It is located at the corner of what was then known as Main Government Road and Valley House Road, a high point within the lands of the Makee Sugar Plantation. (Garden Island April 22, 1930) (Lots of information also from Tyler.)

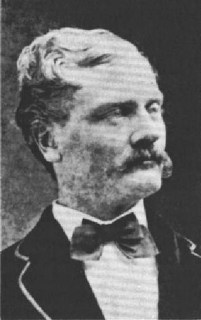

The image shows Zephaniah Swift Spalding. In addition, I have included more related images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+