Most writers romanticize the “ahupua‘a system” solely in the context of ecology and resource management – there is minimal (almost no) discussion that the sociological aspect of the separation and distribution of people may have also played a part in the ahupua‘a.

“(I)n the earliest times all the people were alii … it was only after the lapse of several generations that a division was made into commoners and chiefs” (Malo)

Kamakau noted, in early Hawaiʻi “The parents were masters over their own family group … No man was made chief over another.” Essentially, the extended family was the socio, biological, economic and political unit.

“In very ancient times, the lands were not divided and an island was left without divisions such as kalana, ʻokana, ahupuaʻa, and ʻili, but in the time when the lands became filled with people, the lands were divided, with the proper names for this place and that place so that they could be known.” (Kamakau)

As the population increased and wants and needs increased in variety and complexity (and it became too difficult to satisfy them with finite resources,) the need for chiefly rule became apparent.

The arrival of Pā‘ao from Tahiti in about the thirteenth century resulted in the establishment (or, at least expanded upon) a religious and political code in old Hawai`i, collectively called the kapu system.

Pā‘ao reportedly initiated a lineage of kings, starting with Pili Ka‘aiea (the 1st “Aliʻi ʻAimoku” for the Big Island – the first ruler (sometimes called the “king”) of the island.)

“The common people were called the maka‘ainana, literally ‘on-the-land [folk] .’ According to native genealogical history, they were of the same stock as the ali‘i but without claim to noble status or rank. This was because no strict rules governed their unions, as in the case of the nobility, with respect to genealogical equality or precedence.”

“They were the planters, the fishermen, and the craftsmen. Whether they were planters or fishers, they were tenants, not freeholders. As long as they were loyal to the ali‘i on whose land they dwelt, their land holdings, homesites, and fishing rights were secure.”

“Theirs was the right, if they pleased, to leave their home district or island and settle elsewhere under another chief.” (Pukui and Handy)

Life in the ahupua‘a was not idyllic … “The condition of the common people was that of subjection to the chiefs, compelled to do their heavy tasks, burdened and oppressed, some even to death. The life of the people was one of patient endurance, of yielding to the chiefs to purchase their favor. The plain man (kanaka) must not complain.”

“If the people were slack in doing the chief’s work they were expelled from their lands, or even put to death. For such reasons as this and because of the oppressive exactions made upon them, the people held the chiefs in great dread and looked upon them as gods.”

“Only a small portion of the kings and chiefs ruled with kindness; the large majority simply lorded it over the people.”

“It was from the common people, however, that the chiefs received their food and their apparel for men and women, also their houses and many other things. When the chiefs went forth to war some of the commoners also went out to fight on the same side with them.”

“It was the makaainanas also who did all the work on the land; yet all they produced from the soil belonged to the chiefs; and the power to expel a man from the land and rob him of his possessions lay with the chief.” (Malo)

As populations grew, so did potential for rivalry amongst family and Chiefs.

Just as the ‘divide and rule’ (or, divide and conquer) strategy to create physical divisions among the subjects to prevent alliances that could challenge the ruler helped rulers across the globe centuries prior, it s plausible that was also part of the motivation in dividing the Hawai‘i lands and dispersing the people.

As chiefdoms developed, the simple pecking order of titles and status likely evolved into a more complex and stratified structure. The actual number of chiefs was few, but their retainers attached to the courts (advisors, konohiki, priests, warriors, etc) were many.

In addition to the expanded demand to provide food for the courts, commoners were also obliged to make new lines of products for the chiefs – feather cloaks, capes, helmets, images and ornaments.

Likewise, as challenges were made between chiefly realms, warfare and the resultant demand for services in combat increased. “Maka‘āinana … certainly did march with chiefly retinues on some occasions. The degree to which maka‘āinana were mobilised varied according to the nature of the undertaking, or the seriousness of the threat posed.”

“Kamakau relates that, when an O‘ahu army invaded Moloka‘i in the mid-part of the 18th century, it was not until the fifth day of fighting that every able-bodied man within range of the battlefield came out of his house to fight.”

“Maka‘āinana levies were almost certainly more useful defending their own localities than bolstering forces invading other polities or other islands for logistical reasons. Practice varied.” (D’Archy)

When you look at it (without the influence of the repeated/glamorized descriptors, i.e., it’s all (and only) about resource protection) you can see that the ahupua‘a may also be about sociology (not just ecology).

Yes … because the population was distributed around each of the islands and not concentrated into villages, impacts to the resources are minimized. However, because of the dispersal of people, that also meant potential opponents had a harder time organizing dispersed people against you.

It was not always a peaceful time. Island rulers, Aliʻi or Mōʻī, typically ascended to power through familial succession and warfare. In those wars, Hawaiians were killing Hawaiians; sometimes the rivalries pitted members of the same family against each other.

Going back to Pi‘ilani (generally, about the time Columbus was sailing across the Atlantic) … Pi‘ilani died at Lāhainā and the kingdom of Maui passed to his son, Lono-a-Piʻilani. Pi‘ilani had directed that the kingdom go to Lono, and that Kiha-a-Piʻilani (Lono’s brother) serve under him. In the early years of Lono-a-Piʻilani’s reign all was well; that changed.

Lono-a-Piʻilani became angry, because he felt Kiha-a-Piʻilani was trying to seize the kingdom for himself. Lono sought to kill Kiha; so Kiha fled in secret to Molokaʻi and later to Lānaʻi. When Kiha, with chiefs, warriors and a fleet of war canoes, made their way to attack Lono; Lono trembled with fear of death, and died. (Kamakau)

The same happened when Liloa from Waipio died; Liloa named his son Hakau as heir to his kingdom, Umi, Liloa’s other son was given the Hawaiian god of war Kūkaʻilimoku. The brothers didn’t get along and Umi killed Hakau and took control of the kingdom.

Fast forward to Kamehameha’s time, sibling (and cousin) rivalries continued … Following Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s death in 1782, the kingship was inherited by his son Kīwalaʻō; Kamehameha (Kīwalaʻō’s cousin) was given Kūkaʻilimoku.

Dissatisfied with subsequent redistricting of the lands by district chiefs, civil war ensued between Kīwalaʻō’s forces and the various chiefs under the leadership of his cousin Kamehameha.

In the first major skirmish, in the battle of Mokuʻōhai (a fight between Kamehameha and Kiwalaʻo in July, 1782 at Keʻei, south of Kealakekua Bay on the Island of Hawaiʻi,) Kiwalaʻo was killed by Kamehameha’s forces.

With the death of his cousin Kiwalaʻo, the victory made Kamehameha chief of the districts of Kona, Kohala and Hāmākua, while Keōua, the brother of Kiwalaʻo, held Kaʻū and Puna, and Keawemauhili declared himself independent of both in Hilo. (Kalākaua) Keōua was later killed by Kamehameha Chiefs.

“It is supposed that some six thousand of the followers of this chieftain (Kamehameha,) and twice that number of his opposers, fell in battle during his career, and by famine and distress occasioned by his wars and devastations from 1780 to 1796.”

“However, the greatest loss of life according to early writers was not from the battles, but from the starvation of the vanquished and consequential sickness due to destruction of food sources and supplies – a recognized part of Hawaiian warfare.” (Bingham)

And, shortly after Kamehameha’s death … King Kamehameha II (Liholiho) declared an end to the kapu system. Kekuaokalani, Liholiho’s cousin, opposed the abolition of the kapu system and assumed the responsibility of leading those who opposed its abolition. These included priests, members of his court and the traditional territorial chiefs of the middle rank.

After attempts to settle peacefully, the two powerful cousins engaged at the final battle of Kuamoʻo Liholiho had more men, more weapons and more wealth to ensure his victory. He sent his prime minister, Kalanimōku, to defeat his cousin. Kekauaokalani was killed, as was his wife Manono and his forces were routed.

Dividing the Land

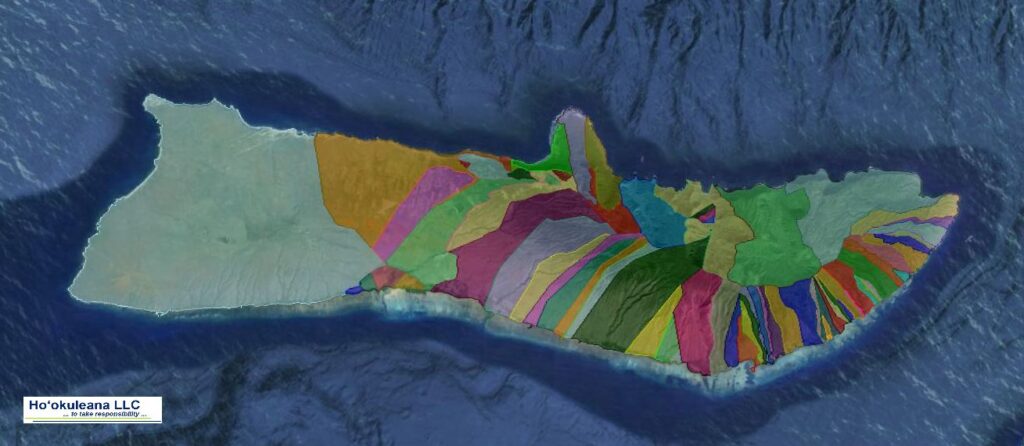

“According to Hawaiian traditions, the system of ahupua‘a divisions was created by rulers who unified or centralized governance of their respective islands, such as Ma‘ilikukahi on O‘ahu and ‘Umi on Hawai‘i Island.” (Gonschor and Beamer)

On Maui, Kalaihaʻōhia, a kahuna (priest, expert,) is credited with the division of Maui Island into districts (moku) and sub-districts, during the time of the aliʻi Kakaʻalaneo at the end of the 15th century or the beginning of the 16th century. (McGerty)

“The people of old gave names for the island’s different parts through their observing until their ideas became clear and precise, there are two names used on an island, moku is a name, ‘aina is another name, lands that were separated by the sea were called moku, lands where people resided were called moku.”

“The island (moku that is surrounded by water) is the main division, like, Hawai‘i, Maui and the rest of the island chain. (Islands) were divided up into sections inside of the island, called moku o loko, like such places as Kona on Hawai‘i island, and Hana on Maui island, and such divisions on these islands.”

“There sections were further divided into subdivision called ‘okana, or kalana; a poko is a subdivision of a ‘okana. These sections were further divided into smaller divisions called Ahupua’a, and sections smaller than an Ahupua‘a were called ‘ili ‘aina.”

“Divisions smaller than ‘ili ‘aina were mo‘o ‘aina and pauku ‘aina, and smaller than a pauku ‘aina was a kihapai, at this section the smaller divisions would be multiple Ko‘ele, Hakuone, and kuakua.” (Malo)

“An ali‘i nui (high chief) ruled the mokupuni. He appointed an ali‘i ‘ai moku (lower chief) to rule each moku. The ali‘i ‘ai moku chose a chief of lesser rank, an ali‘i ‘ai ahupua‘a, to rule the ahupua‘a. Often the ali‘i ‘ai ahupua‘a was not a resident of the ahupua‘a when selected and the title was not hereditary.”

“Sometimes the ali‘i ‘ai ahupua‘a also served as the konohiki (headman) and ran the day-to-day operations of the ahupua‘a. The konohiki managed land use, assisted by luna who were experts in different specialties.” (Kamehameha Schools Press)

The ahupua‘a narrative doesn’t match reality … Look at ahupua‘a mapping and you will see that the ‘watershed’ ‘from the mountain to the sea’ divisions are really anomalies and not the norm for the ahupua‘a in the islands.

“One of the most persistent myths in popular narratives is the idea that ahupua‘a are usually stream drainages bounded by watersheds. Equating ahupua‘a to watersheds is problematic … Furthermore, empirical evidence clearly shows that most ahupua‘a do not correspond to a watershed.” (Gonschor and Beamer)

“Even if applying the most liberal interpretation of the concept, only 98 ahupua‘a (5.4%) can be regarded as bounded by watersheds. Of these there are none on Hawai‘i Island, 15 on Maui, i.e. 2.4% of Maui’s total of 636 ahupua‘a, and 8 of a total of 85 (9.4%) on Moloka‘i.”

“Only O‘ahu with 46 out of a 100 total ahupua‘a (46.0%) and Kaua‘i with 28 out of 82 (34.1%) have significant percentages of watershed-ahupua‘a. The vast majority of ahupua‘a throughout the islands, are regularly shaped (mauka to makai) but not watershed-bounded.” (Gonschor and Beamer)

“We caution … against generalizing the theory of economic self-sufficiency as well. Some, if a relatively small percentage, of the ahupua‘a could clearly not sustain themselves economically but would need to trade with neighboring ahupua‘a, for example, for fish and other marine materials in the landlocked ahupua‘a, and for agricultural products and possibly even fresh water in some of the smaller-sized ahupua‘a in leeward areas.” (Gonschor and Beamer)

So, maybe it’s not all about ecology; maybe sociology played a role, as well.