Today, you don’t necessarily use the words ʻEwa and Kalo in the same sentence – we tend to think of the ʻEwa district as dry and hot, not as a wetland taro production region. Some early written descriptions of the place also note the dry ʻEwa Plains.

In 1793, Captain George Vancouver described this area as desolate and barren: “From the commencement of the high land to the westward of Opooroah (Puʻuloa – Pearl Harbor) was … one barren rocky waste, nearly destitute of verdure, cultivation or inhabitants, with little variation all to the west point of the island. …”

In 1839, Missionary EO Hall described the area between Pearl Harbor and Kalaeloa as follows: “Passing all the villages (after leaving the Pearl River) at one or two of which we stopped, we crossed the barren desolate plain”. (Robicheaux)

However, not only was ʻEwa productive, its taro was memorable.

Ua ʻai i ke kāī-koi o ‘Ewa.

He has eaten the kāī-koi taro of ‘Ewa.

Kāī is O‘ahu‘s best eating taro; one who has eaten it will always like it. Said of a youth or maiden of ‘Ewa, who, like the Kāī taro, is not easily forgotten. (ʻŌlelo Noʻeau, 2770, Pukui)

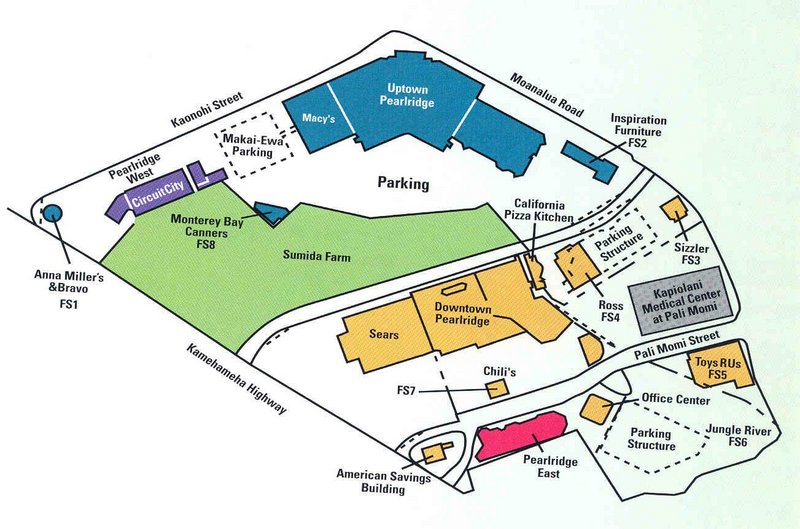

The island of Oʻahu is divided into 6 moku (districts), consisting of: ‘Ewa, Kona, Koʻolauloa, Koʻolaupoko, Waialua and Waiʻanae. These moku were further divided into 86 ahupua‘a (land divisions within a moku.)

‘Ewa was divided into 12-ahupua‘a, consisting of (from east to west): Hālawa, ‘Aiea, Kalauao, Waimalu, Waiau, Waimano, Mānana, Waiʻawa, Waipi‘o, Waikele, Hōʻaeʻae and Honouliuli.

‘Ewa was at one time the political center for O‘ahu chiefs. This was probably due to its abundant resources that supported the households of the chiefs, particularly the many fishponds around the lochs of Puʻuloa (“long hill,) better known today as Pearl Harbor. (Cultural Surveys) ʻEwa was the second most productive taro cultivation area on Oʻahu (just behind Waikīkī.) (Laimana)

The salient feature of ‘Ewa, and perhaps its most notable difference, is its spacious coastal plain, surrounding the deep bays (“lochs”) of Pearl Harbor, which are actually the drowned seaward valleys of ‘Ewa’s main streams, Waikele and Waipi‘o…The lowlands, bisected by ample streams, were ideal terrain for the cultivation of irrigated taro. (Handy, Cultural Surveys)

‘Ewa was known for a special and tasty variety of kalo (taro) called kāī which was native to the district. There were four documented varieties; the kāī ʻulaʻula (red kāī), kāī koi (kāī that pierces), kāī kea or kāī keʻokeʻo (white kāī), and kāī uliuli (dark kāī.) (Handy)

Handy says about ‘Ewa: “The lowlands, bisected by ample streams, were ideal terrain for the cultivation of irrigated taro. The hinterland consisted of deep valleys running far back into the Koʻolau range.”

“Between the valleys were ridges, with steep sides, but a very gradual increase of altitude. The lower parts of the valley sides were excellent for the culture of yams and bananas. Farther inland grew the ‘awa for which the area was famous.”

“The length or depth of the valleys and the gradual slope of the ridges made the inhabited lowlands much more distant from the wao, or upland jungle, than was the case on the windward coast. Yet the wao here was more extensive, giving greater opportunity to forage for wild foods in famine time. (Handy)

Earlier this century, a few fishermen and some of their families built shanties by the shore where they lived, fished and traded their catch for taro at ‘Ewa. Their drinking water was taken from nearby ponds, and it was so brackish that other people could not stand to drink it. (Maly)

An 1899 newspaper account says of the kāī koi, “That is the taro that visitors gnaw on and find it so good that they want to live until they die in ‘Ewa. The poi of kai koi is so delicious”. (Ka Loea Kalai ʻĀina 1899, Cultural Surveys) So famous was the kāī variety that ‘Ewa was sometimes affectionately called Kāī o ‘Ewa.

“I think it (wetlands) went all the way behind the Barbers Point beach area. … We’d go swim in the ponds back there, it was pretty deep, about two feet, and the birds were all around. … It seems like when there were storms out on the ocean, we’d see them come into the shore, but they’re not around anymore.”

“The wet land would get bigger when there was a lot of rain, and we had so much fun in there, but now the water has nearly all dried up. They even used to grow wet-land taro in the field behind the elementary school area when I was young. (Arline Wainaha Pu‘ulei Brede-Eaton, Maly Interview)

”… Bountiful taro fields covered the plain and countless coconut palms, with several huts in their shade beautified the country side. … The taro fields, the banana plantations, the plantations of sugar cane are immeasurable.” (A Botanist’s Visit to Oahu in 1831, Journal of Dr FJF Meyen, Maly)

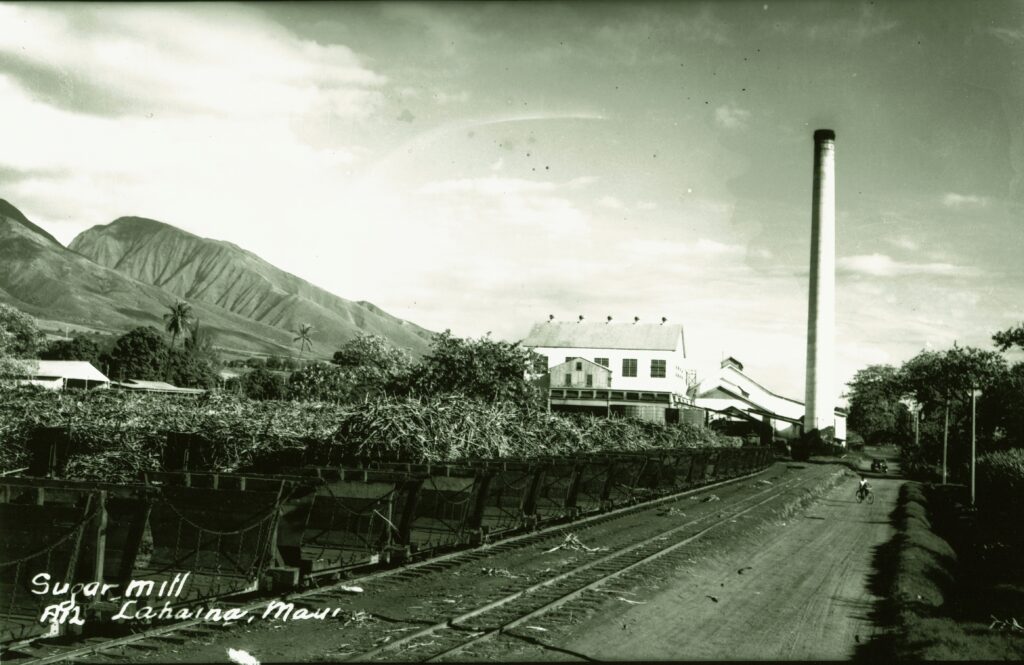

“This district, unlike others of the island, is watered by copious and excellent springs that gush out at the foot of the mountains. From these run streams sufficient for working sugar-mills. In consequence of this supply, the district never suffers from drought, and the taro-patches are well supplied with water by the same means.” (Commander Charles Wilkes, 1840-1841, Maly)

“Rev. Artemas Bishop, in the summer of 1836, removed with his wife and two children from Kailua, Hawaii, to Ewa, Oahu. … Throughout the district of Ewa the common people were generally well fed. Owing to the decay of population, great breadths of taro marsh had fallen into disuse, and there was a surplus of soil and water for raising food.” (SE Bishop, The Friend, May 1901)

As in other areas, kalo loʻi converted to rice patties. “These days at ‘Ewa, the planting of rice is spreading among the Chinese and the Hawaiians, from Hālawa to Honouliuli and beyond. There will come a day when the mother food, taro, shall not be seen on the land.” (Ka Lahui Hawaii, May 3, 1877, Maly)

Of course, in our discussion of the ʻEwa Moku, we need to remember that it ran from Hālawa to Honouliuli and circled Pearl Harbor. Much of the watered wetland taro was produced off of streams from the Koʻolau; however, there is considerable mention of the wetland taro of Honouliuli (what we generally refer to today as ʻEwa.)