James was son of William and Martha (Adams) Campbell, descended from the Scottish Campbell clan, the eighth child in the family of eight boys and four girls (born in Ireland, February 4, 1826.) His father was a carpenter who operated a furniture and cabinet shop adjacent to the home where he and his wife raised their family.

With limited opportunities on that island, at the age of 13, he stowed away on a schooner for Canada and later wound up on a whaler out of New Bedford and was bound for the Pacific. He survived a shipwreck in the South Pacific (Tuamotus) on the way.

He and two shipmates immediately were seized by the Islanders and bound to trees to await their fate. After Campbell fixed the chief’s broken musket, they were freed and accepted as members of the community. A few months later Campbell left the Island by drifting out to a passing schooner that took him to Tahiti, and later (1850) he went to Hawaiʻi.

He settled in Lāhainā, Maui and honed his skill as a carpenter in building and repairing boats and constructing homes. He boarded with a European named Barla and married Barla’s only child, Hannah. There were no children of this marriage, which ended with the death of young Hannah Barla Campbell in 1858.

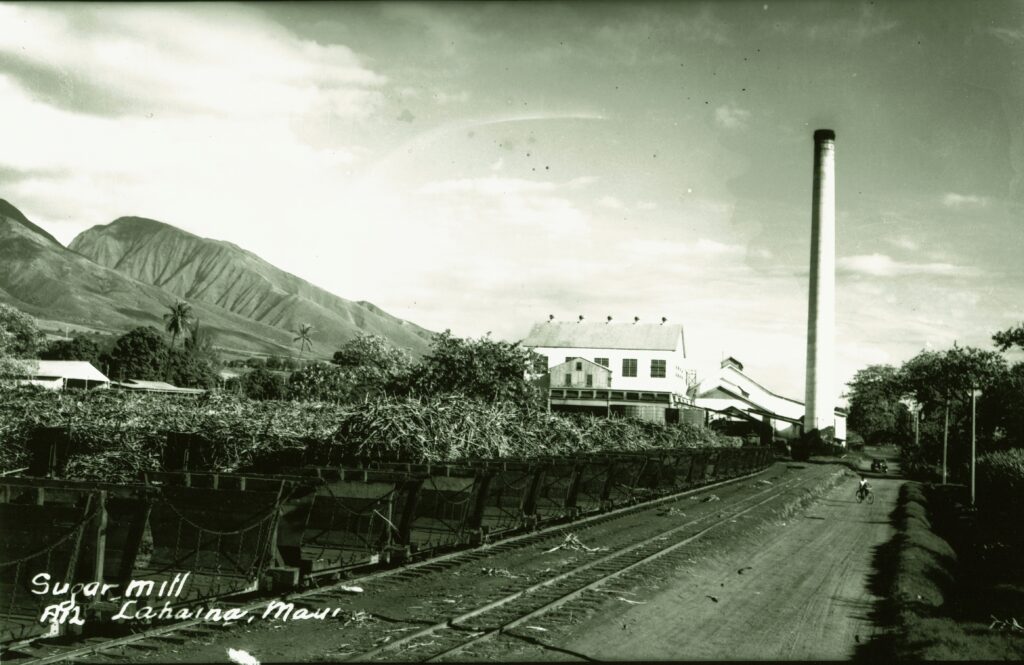

He expanded beyond carpentry and ventured into the Islands’ fledgling sugar industry. In 1860, Campbell, with Henry Turton and James Dunbar, established the Pioneer Mill Company (Dunbar later left;) they not only invested capital in the business, they also worked alongside employees in the field and mill.

When Campbell and Turton were starting the plantation, the small sugar mill consisted of three wooden rollers set upright, with mules providing the power to turn the heavy rollers. The cane juice ran into a series of boiling kettles that originally had been used on whaling ships.

By 1876, the annual production had increased to 1,708-tons of raw sugar and the World’s Fair in Philadelphia awarded Pioneer Mill a prize for its fine quality sugar that year. In 1882, Honolulu Iron Works built an iron three-roller mill for the factory and soon there were six boilers generating steam power to drive the machinery.

Pioneer Mill Company not only survived but thrived and enabled Campbell to build a palatial home in Lāhainā. Despite his success in sugar, his interests turned to other matters, primarily ranching and real estate and he started to acquire lands in Oʻahu, Maui and the island of Hawaiʻi.

In 1876, he purchased approximately 15,000-acres at Kahuku on the northernmost tip of Oʻahu from HA Widemann and Julius L Richardson. In 1877, he acquired from John Coney 41,000-acres of ranch land at Honouliuli.

In 1877, he sold his interest in Pioneer Mill Company to his partner, Turton; he married Abigail Kuaihelani Maipinepine (age 19) and soon after moved to a home on Emma Street in Honolulu, which Campbell purchased from Archibald S Cleghorn in 1878. (Now the site of the Pacific Club.)

Princess Kaʻiulani, daughter of the Cleghorns, was born there in 1875. The Campbells’ first daughter, Abigail Wahiikaahuula, later Princess Abigail Kawānanakoa, was born in the same room as Princess Kaʻiulani. (Other children included Alice, Beatrice and Muriel; four other children were born to the couple but died in infancy.)

In 1883 he built the Campbell Block Building at the corner of Merchant and Fort Streets, Honolulu, where he established his office. (This building was headquarters for the Campbell Estate until 1967, when the Estate constructed the modern James Campbell Building at this site to house its offices.)

In 1885, Pioneer Mill Company, cultivating about 600 of its 900 acres of land and producing about 2,000 tons of sugar a year, encountered difficulties and Turton declared bankruptcy. To protect his mortgage, Campbell, with financial partner Paul Isenberg of Hackfeld and Company, acquired all the stock and Campbell again took on management of the operation.

With major interests on Maui and Oʻahu, Campbell split his time between the Islands. He was a member of the House of Nobles representing Maui, Molokai and Lānaʻi in the special session of 1887 and the regular session of 1888.

Back on Oʻahu, critics scoffed at the doubtful value of Campbell’s purchase of Honouliuli. But he envisioned supplying the arid area with water and commissioned California well-driller James Ashley to drill a well on his Honouliuli Ranch. In 1879, Ashley drilled Hawaiʻi’s first artesian well; Campbell’s vision had made it possible for Hawaiʻi’s people to grow sugar cane on the dry lands of the ʻEwa Plain.

In 1889, Campbell leased about 40,000-acres of land for fifty years to BF Dillingham (of Oʻahu Railway and Land Co;) after several assignments and sub-leases, about 7,860-acres of Campbell land ended up with Ewa Planation.

(ʻEwa Plantation was considered one of the most prosperous plantations in Hawaiʻi and in 1931 a new 50-year lease was executed, completing the agreement with Oʻahu Railway and Land Company and beginning an association with Campbell Estate. The ʻEwa mill closed in the mid-1970s; the mill was demolished in 1985.)

After a lengthy illness, Campbell died on April 21, 1900, in his Emma Street home. On the afternoon of his funeral the banks and most of the large business houses closed. (In January of 1902, Abigail Campbell married Colonel Sam Parker.)

“We knew him then as a very capable and industrious mechanic at Lahaina. By hard work and sound judgment, twenty years later he had built up a valuable sugar plantation in Lahaina. From that beginning of wealth he became the possessor of more than three millions of property, all of it, to the best of our knowledge, honestly gained without detriment to others.”

“Mr. Campbell was a good citizen, although not a religious man. He was remarkable for sound business judgment, capacity for hard persistent effort, and for great personal courage, qualities very commonly accompanying Scotch descent.” (The Friend, May 1, 1900)

When Campbell died, the Estate of James Campbell was created as a private trust to administer his assets for the benefit of his heirs (in 2007, the James Campbell Company succeeded the Estate of James Campbell.) The Estate played a pivotal role in Hawaiʻi history, from the growth of sugar plantations to the growing new City of Kapolei.

Over the years, Campbell became known by the Hawaiians as “Kimo Ona-Milliona” (James the Millionaire.) Campbell himself said that the principle upon which he had accumulated his wealth was in always living on less than he made. (Lots of information here from Campbell Estate publications.)