Waialua (two waters) may refer to the two large stream drainages (Anahulu and Helemano-Poamoho-Kaukonahua) that were once used to irrigate extensive taro fields in the ahupua‘a of Kamananui, Pa‘ala‘a and Kawailoa, the more populous ahupua‘a on the eastern side of the district. The ahupua‘a of Keālia, Kawaihāpai, and Mokulē‘ia, on the western side of the district, were more arid, and were not as well-watered as the three eastern ahupua‘a. (Cultural Surveys)

In 1813, Waialua was described by John Whitman, an early missionary visitor, as: “…a large district on the NE extremity of the island, embracing a large quantity of taro land, many excellent fishing grounds and several large fish ponds one of which deserves particular notice for its size and the labour bestowed in building the wall which encloses it.” (Cultural Surveys)

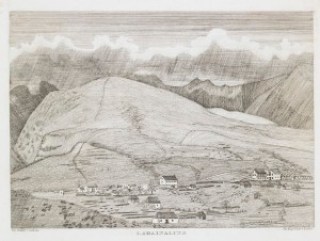

Later (1826,) Levi Chamberlain noted, “The whole district of Waialua is spread out before the eye with its cluster of settlements, straggling houses, scattering trees, cultivated plats & growing in broad perspectives the wide extending ocean tossing its restless waves and throwing in its white foaming billows fringing the shores all along the whole extent of the district.” (Cultural Surveys)

In 1865, Levi and Warren Chamberlain started a sugar plantation in Waialua that ultimately failed, and Robert Halstead bought the Chamberlain plantation in 1874 under the partnership of Halstead & Gordon.

Gordon died in 1888, and the plantation was managed by the Halstead Brothers, Robert and his two sons, Edgar and Frank. In 1898, Castle & Cooke formed the Waialua Agricultural Company and purchased the plantation from the Halstead Brothers. (The mill stayed in operation up until 1996.)

By 1898, the OR&L railroad was constructed along the coast through the Waialua District, with stations in both Kawaihāpai and Mokulēʻia. By the early-1900s, sugarcane plantations and large ranches came to dominate the lands of western Waialua.

“Waialua is reached either by railroad, a distance from Honolulu of 58 miles, or wagon road, 28 miles. The plantation lands extend along the seacoast 15 miles and 10 miles back toward the mountains. The plantation has a good railway system.” (Louisiana Planter, 1910)

To serve the growing population, in 1914, Waialua had a one room school known as Mokulēʻia School with Miss Eva Mitchell as principal. The school served students from Waialua, Haleiwa, Mokulēʻia, Pupukea and Kawailoa. Then, on May 1, 1924, Waialua Agricultural Co. donated five-acres of land where six new classrooms were built.

In 1927, the school was renamed the Andrew E Cox School (Intermediate) in memory of the benefactor who gave the 15-acre tract of land on which Waialua High and Intermediate now stands.

When the County governance structure was adopted in the Territory of Hawaiʻi (1905,) Cox was the first member of the County Board of Supervisors, representing Waialua. He also served as Deputy Sheriff. (Andrew Cox died January 29, 1921 after an illness of several years at the age of 53.)

For a while, Leilehua High School was the only high school in this part of the Island had. Then, in 1936, the Cox Intermediate School was enlarged to include a high school division and the school was renamed Waialua High and Intermediate School.

Charles Nakamura attended Waialua Elementary, Andrew E. Cox Intermediate, and Waialua High Schools. He was Waialua High’s first student body president and member of its first graduating class in 1939. (UH)

Waialua resident Charles Nakamura said high school graduation has been a major event in the Oʻahu community of fewer than 4,000 since the first commencement at the old Andrew E. Cox Auditorium on June 7, 1939. (Honolulu Advertiser)

By 1950, the school enrollment reached 745 students, with a staff of 30 teachers. Today, enrollment is approximately 600 (grades 7-12.)

Waialua High School is an accredited school and offers a curriculum comparable to any high school in the island. Students who are preparing for college have courses such as physics, chemistry, biology, plain and solid geometry, trigonometry, algebra and three language courses to choose from.

For students who are interested in entering the business field, the school offers courses such as shorthand, typing, business math, bookkeeping, office practice and general business. If a student is interested in the technical or vocational field, he/she has shop, agriculture and homemaking to help further his studies.

Waialua High and Intermediate is recognized nationally as one of 11-medal-winning schools from Hawaiʻi (recognized by US News, for performing well on state exit exams, based on students’ mastery of college-level material – all 11-schools received Bronze medals.)

For the last dozen+ years, Waialua has had an award winning robotics team (Na Keiki O Ka Wa Mahope (The Children of the Future) aka Hawaiian Kids.) The team motto is “It’s not about winning … It’s about teamwork, commitment and responsibility.”

The image shows Waialua High and Intermediate School logo. In addition, I have added other images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook