As molten lava flows, its surface cools; the lava then flows underground, forming tubes. When the eruption stops, lava drains from the tube, leaving it an open chamber. Sea caves also can form with openings in the roof.

Near the ocean, this can form a blowhole. As waves rush toward the rock, the water is compressed as it moves upward, erupting into a spray of water, not unlike a small geyser.

Blowholes are sometimes called “spouting horns” because of the loud roaring noises created by the rushing air and water coming up the chimney.

Hālona Blowhole on Oʻahu’s eastern coastline has a narrow opening, but then it opens up about eight-feet below the surface. The waves crashing against the shoreline rush through, sending a spout of water and spray up to 30-feet into the air.

Ha-Lo-Na is literally saying – See The Foundation Breathe or Look At The Breath Of The Foundation. Ancient Hawaiians may have found it – just like us – to be a marvel and entertaining to watch – and perhaps as stupid as some to challenge it. (Yardley)

It is one of Oʻahu’s busiest brief stops, for residents and visitors alike.

It gained attention years ago, and a lookout was initially built in the early-1950s; railings were added in 1971.

In 2008, a $1-million renovation project replaced a lower viewing platform that collapsed in 1997, added stainless-steel railings and a sitting area. An expanded 42-stall parking lot, including two bus spots, was repaved, and an accessible sidewalk was added.

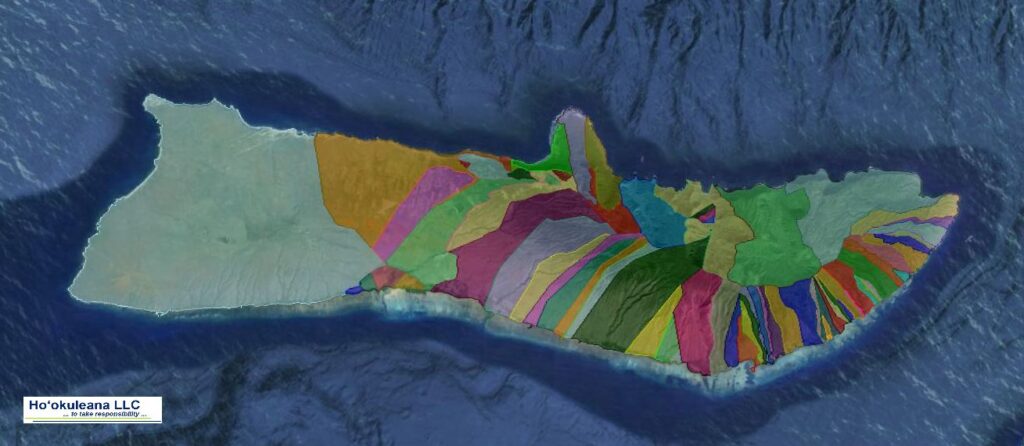

Viewing is not limited to the blowhole; on a clear day, the islands of Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi and Maui can be seen from the lookout (an etched compass of Oʻahu and a map shows the island locations.)

It is not safe to go down to the blow hole. Numerous signs warn of the hazards of getting too close. However, that doesn’t seem to stop people from trying (and dying.)

Since 1927, four people have been swept into the blowhole; three men have died in 1969, 1986 and 2002, one man survived in 1967.

Likewise, a list of SCUBA fatalities since 1971 shows that more fatalities occur at Hālona Blow Hole than any other dive site in the state. (shorediving)

The sea cliffs that make this stretch of shoreline so great for diving also preclude any easy exit sites. This, coupled with the strong current, slippery rocks, waves on the ledges and lack of lifeguards makes this coast one of the most hazardous on the island.

Nearby is Hālona Cove (to the right as you look out,) it’s a small pocket of sand that has a history of its own.

It was here, in the 1953 film ‘From Here to Eternity,’ that Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster shared the kiss as a wave rolled in. The location also served as a scene in the ‘Pirates of the Caribbean IV,’ ’50 First Dates’ and Nikki Minaj’s ‘Starships.’