Kapa‘a was the final home of the legendary chief Mō‘īkeha. Born at Waipi‘o on the island of Hawai‘i, Mō‘īkeha sailed to Kahiki (Tahiti), the home of his grandfather, Maweke, after a disastrous flood. On his return to Hawai‘i, he settled at Kapa‘a, Kauai.

Kila, Mō‘īkeha’s favorite of three sons by the Kauai chiefess Ho‘oipoikamalanai, was born at Kapa‘a and was considered the most handsome man on the island. It was Kila who was sent by his father back to Kahiki to slay his old enemies and retrieve a foster son, the high chief La‘amaikahiki.

Mō‘īkeha’s love for Kapa‘a is recalled in the ‘olelo no‘eau: Ka lulu o Mo‘ikeha i ka laulã o Kapa‘a “The calm of Mō‘īkeha in the breadth of Kapa‘a ” (Pukui 1983: 157) (McMahon)

The sugar industry came to the Kapa‘a region in 1877 with the establishment of the Makee Sugar Company and subsequent construction of a mill near the north end of the present town. Cane was cultivated mainly in the upland areas on former kula lands

The first crop was planted by the Hui Kawaihau, a group composed of associates of King Exploration Associates Ltd. David Kalākaua. The king threw much of his political and economic power behind the project to ensure its success.

The Hui Kawaihau was originally a choral society begun in Honolulu whose membership consisted of many prominent names, both Hawaiian and haole.

It was Kalākaua’s thought that the Hui members could join forces with Makee, who had previous sugar plantation experience on Maui, to establish a successful sugar corporation on the east side of Kauai. Captain Makee was given land in Kapa‘a to build a mill and he agreed to grind cane grown by Hui members.

Kalākaua declared the land between Wailua and Moloa‘a, the Kawaihau District, a fifth district and for four years the Hui attempted to grow sugar cane at Kapahi, on the plateau lands above Kapa‘a.

Kapa‘a town was founded by immigrant sugar workers who left their sugar mill towns and set up small private businesses. It is one of only two towns on Kauai that sprang up independent of sugar production.

Pineapple became the next largest commercial enterprise in the region. In the early 1900s, to help with the growing plantation population, government lands were auctioned off as town lots in Kapa‘a.

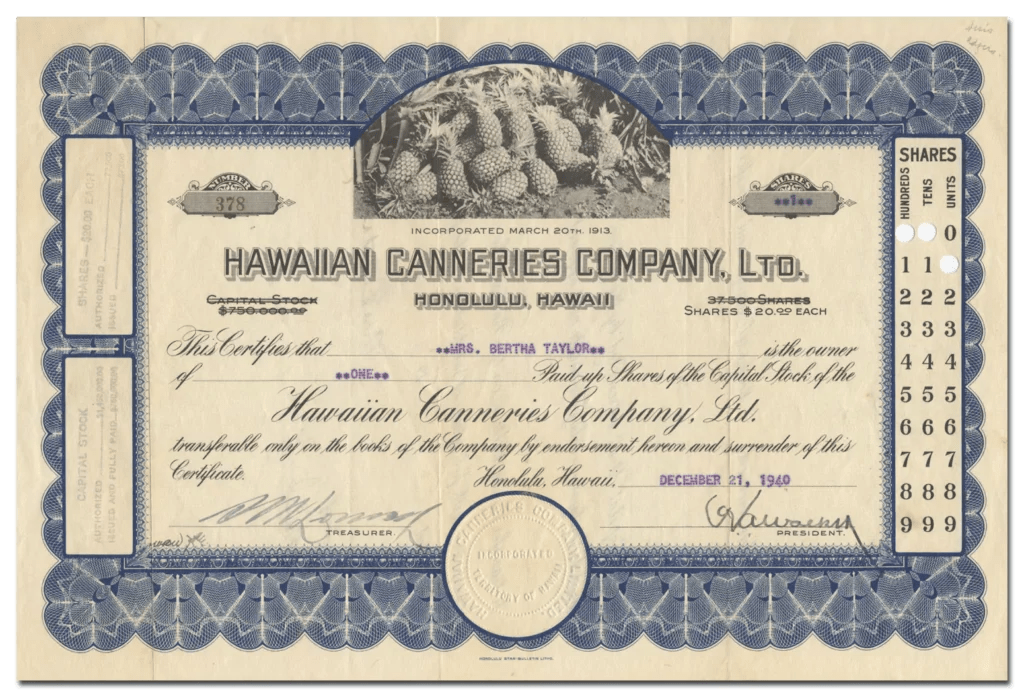

The first pineapple company on the island of Kauai was established in 1906. In 1913, Hawaiian Canneries Company, Ltd opened in Kapa‘a. Through the Hawaiian Organic Act, Hawaiian Canneries purchased land they were leasing, approximately 8.75 acres, in 1923.

Hawaiian Canneries Co. cultivated pineapple scattered over 35 miles from Hanamaulu to Hanalei and processed and canned its pineapple at Kapa‘a canneries (now the site of Pono Kai Resort). (McMahon)

The Kapa‘a Cannery provided employment for many Kapa‘a residents. By 1960, 3400 acres were in pineapple and there were 250 full time employees and 1000 seasonal employees for the Kapa‘a Cannery.

On August 21, 1929, a US trademark registration was filed for ‘Pono’ by Hawaiian Canneries. The description provided to the trademark for Pono is ‘canned sliced and crushed pineapple and pineapple juice used for food-flavoring purposes’. (Trademarkia) By 1956, the cannery was producing 1.5 million cases of pineapple.

Factory by-products – the crowns & skins from the processed pineapples – were loaded onto train carts and hauled up the coast to a pier. The pineapple rubbish was then dumped into the ocean from the end of the pier. (Kauai Path)

As canned pineapple from other countries began filling the market, Hawaiian canneries began to close and plantations, once located on Maui, Oahu, Molokai, Lanai, and Kauai, began to shrink.

In 1962, Hawaiian Canneries went out of business due to foreign competition. (Exploration) Other smaller Kauai and Maui pineapple companies closed in the late-1960s.

In 1969, Hawaiian Fruit Packers (which was formed in 1937 by the reorganization of a company initially started by a group of ethnic Japanese growers) on Kauai, the last cannery remaining there, announced plans to cease planting. The cannery was closed in October 1973. (Bartholomew etal)

Del Monte cannery closed in 1985, and Dole cannery in Iwilei closed in 1991. The Kahului cannery of Maui Land and Pineapple Company was the last remaining pineapple cannery in Hawai‘i.

The Hawaiian pineapple industry has gone from its early days as a primarily fresh product, through most of the 20th century as principally a canned product and a major supplier of the worlds canned pineapple market, to the 21st century when it is once again grown mostly for fresh consumption. (HAER)