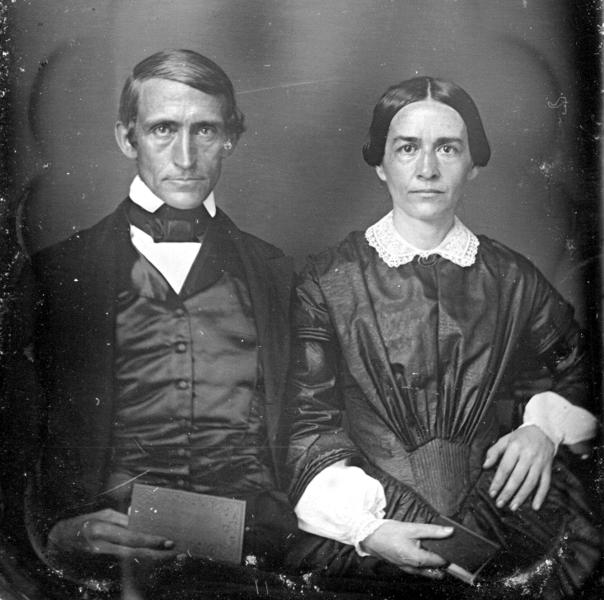

Daniel Dole was born in Bloomfield (now Skowhegan,) Maine, September 9, 1808. He graduated from Bowdoin College in 1836 and Bangor Theological Seminary in 1839, and then married Emily Hoyt Ballard (1807-1844,) October 2, 1840 in Gardiner, Maine.

The education of their children was a concern of missionaries. There were two major dilemmas, (1) there were a limited number of missionary children and (2) existing schools (which the missionaries taught) served adult Hawaiians (who were taught from a limited curriculum in the Hawaiian language.)

During the first 21-years of the missionary period (1820-1863,) no fewer than 33 children were either taken back to the continent by their parents. (Seven-year-old Sophia Bingham, the first Caucasian girl born on Oʻahu, daughter of Hiram and Sybil, was sent to the continent in 1828. She is my great-great-grandmother.)

On July 11, 1842, fifteen children met for the first time in Punahou’s original E-shaped building. The first Board of Trustees (1841) included Rev. Daniel Dole, Rev. Richard Armstrong, Levi Chamberlain, Rev. John S Emerson and Gerrit P Judd. (Hawaiian Gazette, June 17, 1916)

By the end of that first year, 34-children from Sandwich Islands and Oregon missions were enrolled, only one over 12-years old. Tuition was $12 per term, and the school year covered three terms. (Punahou)

By 1851, Punahou officially opened its doors to all races and religions. (Students from Oregon, California and Tahiti were welcomed from 1841 – 1849.)

December 15 of that year, Old School Hall, “the new spacious school house,” opened officially to receive its first students. The building is still there and in use by the school.

“The founding of Punahou as a school for missionary children not only provided means of instruction for the children, of the Mission, but also gave a trend to the education and history of the Islands.”

“In 1841, at Punahou the Mission established this school and built for it simple halls of adobe. From this unpretentious beginning, the school has grown to its present prosperous condition.” (Report of the Superintendent of Public Education, 1900)

The curriculum at Punahou under Dole combined the elements of a classical education with a strong emphasis on manual labor in the school’s fields for the boys, and in domestic matters for the girls. The school raised much of its own food. (Burlin)

Some of Punahou’s early buildings include, Old School Hall (1852,) music studios; Bingham Hall (1882,) Bishop Hall of Science (1884,) Pauahi Hall (1894,) Charles R. Bishop Hall (1902,) recitation halls; Dole Hall and Rice Hall (1906,) dormitories; Cooke Library (1908) and Castle Hall (1913,) dormitory.

Dole Street, laid out in 1880 and part of the development of the lower Punahou pasture was named after Daniel Dole (other nearby streets were named after other Punahou presidents.)

Emily died on April 27, 1844 in Honolulu; Daniel Dole married Charlotte Close Knapp (1813-1874) June 22, 1846 in Honolulu, Oʻahu.

Daniel Dole resigned from Punahou in 1855 to become the pastor and teacher at Kōloa, Kauai. There, he started the Dole School that later became Kōloa School, the first public school on Kauai. Like Punahou, it filled the need to educate mission children.

The first Kōloa school house was a single room, a clapboard building with bare timbers inside and a thatched roof. Both missionary children as well as part-Hawaiian children attended the school. (Joesting)

Due to growing demand, the school was enlarged and boarding students were admitted. Reverend Elias Bond in Kohala sent his three oldest children to the Kōloa School, as did others from across the islands. (Joesting)

Charlotte died on Kauai in 1874 and Daniel Dole died August 26, 1878 in Kapaʻa, Kauai. Dole’s sons include Sanford Ballard Dole (President of the Republic of Hawaiʻi and 1st Territorial Governor of Hawaiʻi.) Daniel Dole was great uncle to James Dole, the ‘Pineapple King.’