Ka niu peʻahi kanaka o Kaipalaoa.

The man-beckoning coco palms of Kaipalaoa.

(The swaying palms that once grew at Kaipalaoa, Hilo, seemed to wave an invitation. ʻŌlelo Noʻeau #1502)

Hilo is likely to have been one of the first Polynesian settlement areas on Hawai‘i Island; oral history and local legend indicate that Polynesians first settled Hilo Harbor around 1100 AD.

Early accounts of Hilo Bay describe a long black sand beach stretching along present day Bay Front from the Wailuku River to the Wailoa River.

Many heiau (temples) attested to the prosperity of Hilo. Kaipalaoa (Sea Whale) Heiau sat on the southern banks. The village at Kaipalaoa was a major trade center, where people from the northern districts met the people of the southern portions of Hilo and Puna.

Kamehameha was familiar with the Hilo district from his youth. Kaipalaoa, across the Wailuku River from Pu`u`eo was a favorite surfing area, and at least eight excellent breaks could be found from Pu‘u‘eo to Waiākea. (Yuen)

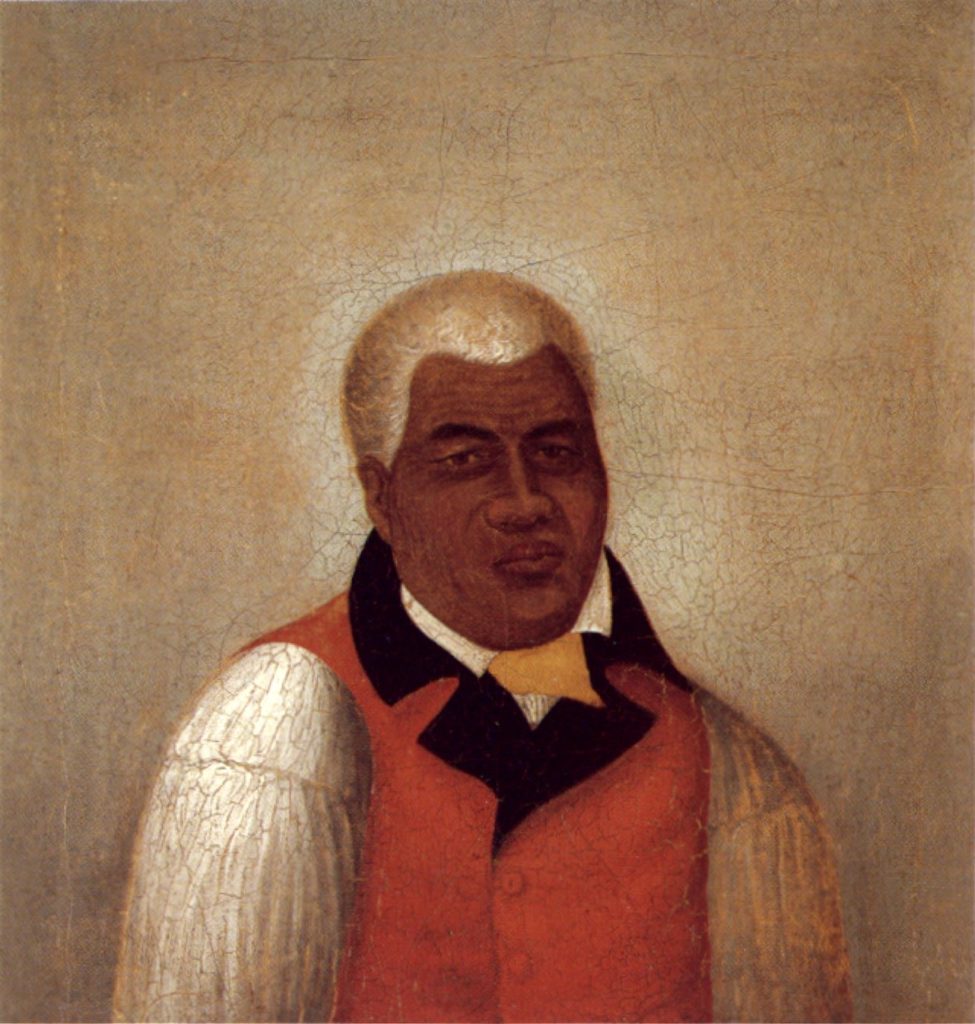

Kamehameha I began a war of conquest, winning his first major skirmish in the battle of Mokuʻōhai (a fight between Kamehameha and Kiwalaʻo in July, 1782 at Keʻei, south of Kealakekua Bay on the Island of Hawaiʻi.) Kiwalaʻo was killed.

Captain George Vancouver, an early European explorer who met with Kamehameha at Hilo Bay in 1794, recorded that Kamehameha was there preparing for his invasion of the neighbor islands, and that Hilo was an important center because his canoes were being built there.

Desha wrote that “It is thought that there were as many as seven mano [twenty eight thousand] people who gathered at the shore at Kaipalaoa when the ali‘i landed”. The people of Hilo had long prepared for Kamehameha’s arrival and collected a large number of hogs and a variety of plant foods, to feed the ruler and his warriors.

Kelly surmised that the people of Hilo had actually prepared for a year prior to Kamehameha’s visit and expanded their fields into the open lands behind Hilo to accommodate the increased number of people that would be present.

Kelly also speculated that many of the fishponds in Waiākea were created to feed Kamehameha, his chiefs, and craftsmen. The area at Hilo Bay that housed Kamehameha’s canoe fleets continues to be the site of canoeing, both recreational and competitive. (Rechtman)

By 1795, having fought his last major battle at Nuʻuanu on O‘ahu with his superior use of modern weapons and western advisors, he subdued all other chiefdoms (with the exception of Kauai).

However, after a short time, another chief entered into a power dispute with Kamehameha; his name was Nāmakehā (the brother of Kaʻiana, a chief of Kauai who had been killed in the Battle of Nuʻuanu.)

Previously, Kamehameha asked Nāmakehā (who lived in Kaʻū, Hawai‘i) for help in fighting Kalanikūpule and his Maui forces on O‘ahu, but Nāmakehā ignored the request.

Kamehameha, on Oʻahu at the time, returned to his home island of Hawaiʻi with the bulk of his army to suppress the rebellion. The battle took place at Kaipalaoa, Hilo. Kamehameha defeated Nāmakehā.

This was the final battle fought by Kamehameha to unite the archipelago. (Kamehameha negotiated a settlement with King Kaumualiʻi for the control of Kauai and Niʻihau, in 1810.)

Although Kamehameha’s warriors had won the battle over Nāmakehā, they then turned their rage upon the villages and families of the vanquished. It was about the same time and place of the Nāmakehā Rebellion that Kamehameha decreed Ke Kānāwai Māmalahoe (The Law of the Splintered Paddle.)

When Liholiho was born at Hilo in November 1797, he was immediately taken from his mother and given to the guardianship of Kaahumanu. (Sinclair) The first-born child of Keōpūolani and Kamehameha, his piko was ceremonially cut at Kaipalaoa, at the heiau of the same name. (Correa)

Stokes included descriptions of Kaipalaoa heiau as: “Probably located just west of Isabelle Point. The native name of this point is Kaipalaoa”. (Scheffel)

Kaipalaoa Point is now known as Cocoanut Point. “The native name of [Isabelle Point] is Kaipalaoa.” (Stokes) Isabel and Kaipalaoa points are separated by only about three hundred feet. (Hawaiian Place Names)

“The site of Kai-palaoa Heiau was on the land of Kai-palaoa, and lay just seaward, and a little toward Wai-anuenue St, from the site of the Hilo Armory at the upper end of the short street from the shore to Ke-awe St, and on the side toward the river a little below the bridge to Pu-u-eo, near the Library.”

“The Armory site was formerly occupied by the royal residence of King Ka-mehameha I, which was named Ka-hale-‘ilio-‘ole – The House Without Rats (or, commoners).” (Kekahuna)

Kaipalaoa heiau is “Near armory site, Hilo; of pookanaka class; the heiau at which Umi’s life was threatened, and the place where Kamehameha is said to have proclaimed his Māmalahoe law (Law of the Splintered Paddle). Destroyed in the time of Kuakini’s governorship of Hawaii.” (Hawaiian Place Names)

Between 1863 and 1890 a landing wharf and US Coast Guard lighthouse were built at the foot of Waiānuenue Avenue. Passengers and freight were transported to steamers anchored in the bay. (HHF & Cultural Surveys)

By 1870, three heiau in Hilo – Kaipalaoa, Kanowa/Kanoa, and Honokawailani – were described as already being “ruins”. Lydgate describes the Hilo bay front area as it looked in 1873:

“The sea at that time came right up to the bank edge of Front street, so that in heavy weather the spray blew more or less up into the street. Along Front street tall coconut trees of great age towered up over the street.”

“From the foot of Church street extending along the beach it was open country, with the exception of one Hawaiian home, one canoe-builder’s workshop – or halau, as it is called by the Hawaiians – and a tumbled down little blacksmith shop some distance farther on.” (Hawaii County)