Nowhere on the island of Hawaiʻi do the palms grow taller than in the valleys of Waipiʻo, and nowhere is the foliage greener, for every month in the year they are refreshed with rains, and almost hourly cooled in the shadows of passing clouds. (Kalākaua)

Waipi‘o (“curved water”) is one of several coastal valleys on the north part of the Hāmākua side of the Island of Hawaiʻi. A black sand beach, three-quarters of a mile long, fronts the valley, the longest on the Big Island.

For two hundred years or more, Waipiʻo Valley was the Royal Center to many of the rulers on the Island of Hawaiʻi, including Pili lineage rulers – the ancestors of Kamehameha – and continued to play an important role as one of many royal residences until the era of Kamehameha. (UH DURP)

Royal Centers were where the aliʻi resided; aliʻi often moved between several residences throughout the year. The Royal Centers were selected for their abundance of resources and recreation opportunities, with good surfing and canoe-landing sites being favored.

The Hawaiian court was mobile within the districts or kingdom the aliʻi controlled. A paramount’s attendants might consist of as many as 700 to 1000-followers made of kahuna and political advisors (including geologists, architects, seers, messengers, executioner, etc.); servants which included craftsmen, guards, stewards; relatives and numerous hangers-on (friends, lovers, etc.).

Although thinly populated now, Waipiʻo was for many generations in the past a place of great political and social importance, and the tabus of its great temple were the most sacred in all Hawaiʻi. It was the residence of the kings of that island, and was the scene of royal pageants, priestly power and knightly adventure, as well as of many sanguinary battles. (Kalākaua)

Waipiʻo valley was first occupied as a royal residence by Kahaimoelea, near the middle or close of the thirteenth century, and so continued until after the death of Līloa, about the end of the fifteenth century. (Kalākaua)

Līloa, the son of Kiha and father of ʻUmi, had become the peaceful sovereign of Hawaiʻi; Kahakuma, the ancestor of some of the most distinguished families of the islands, held gentle and intelligent sway in Kauai; Kawao still ruled in Maui, and Piliwale in Oʻahu. (Kalākaua)

The reign of Kiha was long and peaceful. He was endowed not only with marked abilities as a ruler, but with unusual physical strength and skill in the use of arms. In addition to these natural advantages and accomplishments, which gave him the respect and fear of his subjects. (Kalākaua)

The reign of his son Līloa was as peaceful as that of Kiha, his distinguished father (Līloa ruled about the same time that Columbus crossed the Atlantic.) He did not lack ability, either as a civil or military leader.

Līloa’s wife, Pinea, was the younger sister of his mother from a line of chiefs on O‘ahu. They had a son, Hākau. From another wife, Haua, a Maui chiefess, he had a daughter, Kapukini. Both of these marriages established ties between high-ranking families outside the Kingdom of Hawai‘i Island. (MalamaWaipio)

Līloa was much given to touring through the districts of his kingdom, by which means he acquainted himself with the needs of his people and was able to repress the arbitrary encroachments of the chiefs on the rights of the land-holders under their authority. In this way he gained popularity with the common people. (Malo)

The story of another of Līloa’s sons, ʻUmi, suggests that while Līloa was on a journey across Hāmākua he met a beautiful woman, Akahiakuleana (Akahi.) They spend the night together and conceive a child. Līloa told Akahi that if she has a son, to name him ʻUmi.

Līloa left his malo (loincloth), his niho-palaoa (whale-tooth necklace) and laʻau palau (club) to be given to the child as proof of ancestry. ʻUmi later united with Līloa and ultimately ruled the Island of Hawaiʻi (he moved the Royal Center from Waipiʻo to Kailua (Kona.))

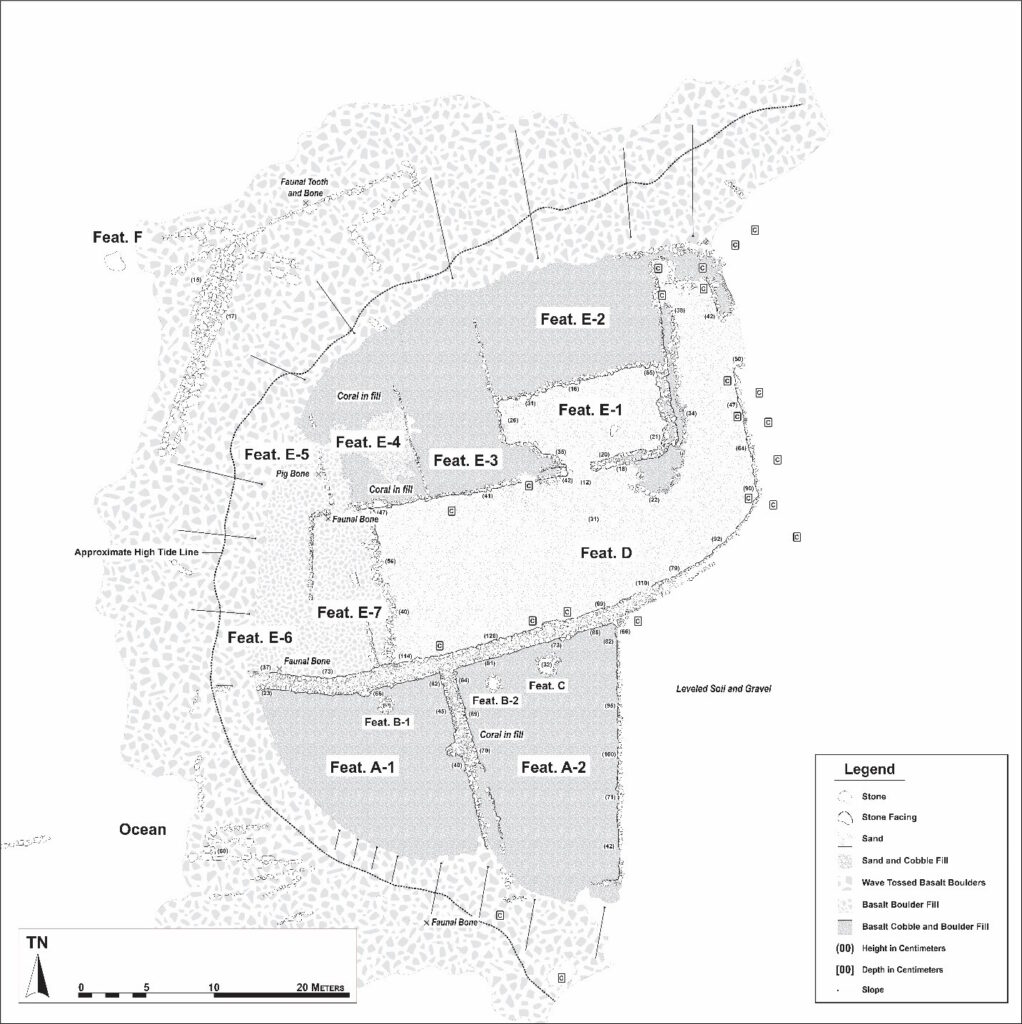

At Waipiʻo, Pakaʻalana was the name of Līloa’s heiau. It is not known by whom the Pakaʻalana heiau was built, but it existed before Kiha’s time and so did the sacred pavement leading to the enclosure where the chief’s Royal Center – called Haunokamaahala – stood, though its name has come down to our days as Paepae-a-Liloa. (Fornander)

“It was a large enclosure, less extensive, however, than that at Honaunau….In the midst of the enclosure, under a wide-spreading pandanus, was a small house, called Ke Hale o Riroa (The House of Līloa), from the circumstance of its containing the bones of a king of that name…..”

“We tried, but could not gain admittance to the pahu tabu, or sacred enclosure. We also endeavored to obtain a sight of the bones of Riroa, but the man who had charge of the house told us we must offer a hog before we could be admitted”. (Ellis 1826)

Līloa carried a long stone on his shoulder and placed it at the side door of his house. He called this stone “The Sacred Slab of Līloa,” (Ka paepae kapu o Līloa). No one, not even a chief was allowed to stand or walk on this stone. Only two people were allowed to step on “The Sacred Slab of Līloa:” Līloa, the ruler, and Chief Laea-nui-kau-manamana. (Williams)

“The expression ‘Ka Paepae Kapu a Liloa’ as at present used, whether in speaking or writing, refers to the reigning sovereign as to the sacredness of trust imposed upon and reposed to him, and as to the dignity and honour of the position where no intruders are supposed to trespass. It also refers to the pavement and the way that leads up to royalty, and as to the footstool of sovereignty and power.” (Bacchilega)

Although the glory of the old capital departed with its abandonment as the royal residence, the tabus of its great temple of Pakaʻalana continued to command supreme respect until as late as 1791, when the heiau was destroyed, with all its sacred symbols and royal associations, by the confederated forces of Maui and Kauai in their war with Kamehameha I. (Kalakaua)

“There are many references to this famous place (Pakaʻalana) … the tabus of its (Waipi‘o) great heiau were the most sacred on Hawaiʻi, and remained so until the destruction of the heiau and the spoliation of all the royal associations in the valley of Waipi‘o by Kāʻeokūlani, king of Kauai, and confederate of Kahekili, king of Maui, in the war upon Kamehameha I, in 1791 …” (Stokes)

King Kalākaua moved the slab (Ka Paepae Kapu a Liloa) to Honolulu. It sits silently and often unnoticed, outside the Archives Building on the grounds of ʻIolani Palace. The stone holds the historical and cultural significance of a Royal Center in Waipiʻo associated with Līloa; he was “sacred in the eyes of his people for his many good qualities.” (Bacchilega)

An ancient chant, later put to music, notes: Aia i Waipiʻo Pākaʻalana e; Paepae kapu ʻia o Līloa e (There at Waipiʻo is Pākaʻalana; And the sacred platform of Līloa.)

The March 10, 1899 issue of the Hawaiian Gazette noted that Līloa (1500s,) Lonoikamakahiki (late-1500s) and Alapaʻi (1700s) are among the reburied at Mauna ʻAla.

It is believed that the corner stones used in the construction of Mokuaikaua Church (1837) and Hulihee Palace (1838) were Līloa and ʻUmi stones.