John Adams Kuakini Cummins was born March 17, 1835 in Honolulu. He was a namesake of island governor John Adams Kuakini (1789–1844), who had taken the name of John Quincy Adams when Americans first settled on the islands in the 1820s.

His father was Thomas Jefferson Cummins (1802–1885) who was born in Lincoln, England, raised in Massachusetts and came to the Hawaiian Islands in 1828. His mother was High Chiefess Kaumakaokane Papaliʻaiʻaina (1810–1849) who was a distant relative of the royal family of Hawaiʻi.

In the 1840s, his father first developed a cattle ranch and horse ranch. Facing diminishing returns in the cattle market, in the 1880s, John began to grow sugar cane in place of cattle. This plantation was known as the Waimanalo Sugar Company.

He married Rebecca Kahalewai (1830–1902) in 1861, also considered a high chiefess, and had five children with her, four daughters and one son.

Cummins was elected to the House of Representatives in the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1874. King Kalākaua appointed him to the Privy Council on June 18, 1874 shortly after Kalākaua came to the throne.

Even though Cummins voted against former Queen Emma in the election, she asked him to manage a trek for her around the islands in November 1875.

He had staged a similar grand tour the year before for Kalākaua. Emma was not disappointed.

Although many ancient Hawaiian customs had faded (due to influence of conservative Christian missionaries, for example), Cummins staged great revivals of ceremonies such as traditional hula performance.

In the legislature he advocated for the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 with the United States, which helped increase profits in the sugar industry, and his fortunes grew.

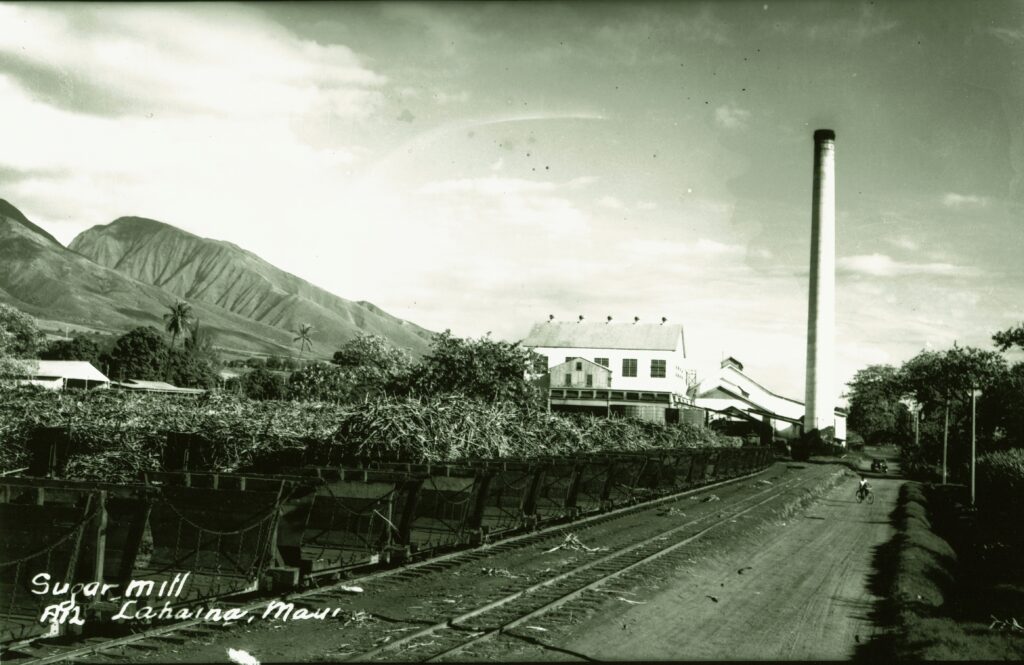

The sugar industry became a huge success and gave way to other innovations in the area. For instance, the use of railway tracks and locomotive were due to the boom of the sugar business.

Cummins left the sugar business to William G Irwin, agent of Claus Spreckles, and developed a commercial building called the Cummins Block at Fort and Merchant streets in Downtown Honolulu.

In 1889, he represented Hawaiʻi at the Paris exposition known as Exposition Universelle. On June 17, 1890 Cummins became Minister of Foreign Affairs in Kalākaua’s cabinet and thus was in the House of Nobles of the legislature for the 1890 session.

When Kalākaua died and Queen Liliʻuokalani came to the throne in early 1891, she replaced all her ministers. Cummins resigned February 25, 1891. He was replaced by Samuel Parker who was another part-Hawaiian.

Cummins was elected to the 1892 session of the House of Nobles, on the Hawaiian National Reform Party ticket. He also organized a group called the Native Sons of Hawaii which supported the monarchy.

After the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in early 1893, Liliʻuokalani asked Cummins to travel to the continent to lobby for its help in restoration of the monarchy.

The task, which included Parker and Hermann A Widemann, ended in failure. However, on the voyage to the west coast, William T Seward, a former Major in the American Civil War who worked for Cummins and lived in one of his homes, smuggled guns and ammunition for the failed 1895 counter-revolution.

Thomas Beresford Walker, Cummins’ son-in-law (married to his eldest daughter Matilda,) was also implicated in the plot. Cummins was arrested, charged with treason and convicted. He was sentenced to prison, but released after paying a fine and agreeing to testify against the ones actively involved in the arms trading.

He died on March 21, 1913 from influenza after a series of strokes and was buried in Oʻahu Cemetery. Well liked, even his political opponents called him “the playmate of princes and the companion and entertainer of kings”. The territorial legislature had tried several times to refund his fine, but it was never approved by the governor.

His funeral was a mix of mostly traditional symbols of the Hawaiian religion, with a Christian service in the Hawaiian language, attended by both royalists and planners of the overthrow.

Cummin’s great-grandson (through his daughter Jane Piikea Merseberg) was Mayor Neal Blaisdell.