“It was said that on a certain night of heavy down pouring rain – the lightning struck its wrathful flashes into the sky – the thunder pounded with all its might – the stormy wind veered every which way – the red water churned in the streams.” (Poepoe, Ahlo)

The child born that night was of royal blood, and was destined to become not only the king of Hawaiʻi, but the conqueror and sovereign of the group.

They say the child was poʻolua, “that is, a child of two fathers, (it) was considered a great honor by chiefs of that period.” (Luomala) Some say that his mother, Kekuʻiapoiwa (married to Keōua,) had a liaison with Kahekili (ruler of Maui.)

Though Kahekili was thought to possibly be his biological father, he was raised by his parents (and was considered the son of Kekuʻiapoiwa and Keōua.)

The exact year of his birth is not known; different historians/writers place the year of his birth from about 1736 to 1759.

He was said to be born at Kokoiki (”little blood,” referring to the first signs of childbirth – Kokoiki is one of the star names listed in the Kumulipo chant.)

Another notes, “(A) bright and beautiful star, appeared at Kokoiki on the night before the child was born and is hence called Kokoiki.” (Kūʻokoʻa Home Rula, Ahlo) (Scientific study places Halley’s Comet in the same relative position in the Hawaiian sky on December 1, 1758. (Ahlo))

Keʻāulumoku predicted that he “would triumph over his enemies, and in the end be hailed as the greatest of Hawaiian conquerors.” (Kalākaua)

Word went out to find and kill the baby, but the Kohala community conspired to save him.

“A numerous guard had been set to wait the time of birth. The chiefs kept awake with the guards (for a time,) but due to the rain and the cold, the chiefs fell asleep, and near daybreak Kekuʻiapoiwa went into the house and, turning her face to the side of the house at the gable end, braced her feet against the wall.”

“A certain stranger (Naeʻole) was outside the house listening, and when he heard the sound of the last bearing-down pain (kuakoko), he lifted the thatch at the side of the house, and made a hole above.”

“As soon as the child was born, had slipped down upon the tapa spread out to receive it, and Kekuʻiapoiwa had stood up and let the afterbirth (ewe) come away, he covered the child in the tapa and carried it away.” (Kamakau)

The young child, Kamehameha, was carried on a perilous journey through Kohala and Pololū Valley to Awini. (KamehamehaDayCelebration)

Hawi, meaning ”unable to breathe,” was where the child, being spirited away by a servant, required resuscitation and nursing. Kapaʻau, meaning ”wet blanket,” was where heavy rain soaked the infant’s kapa (blanket.) Halaʻula (scattered blood) was the town where soldiers were killed in anger. (Sproat – (Fujii, NY Times)) Some believe Kamehameha also spent much of his teen years in Pololū (long spear.)

“Kamehameha (Kalani Pai‘ea Wohi o Kaleikini Keali‘ikui Kamehameha o ‘Iolani i Kaiwikapu Kaui Ka Liholiho Kūnuiākea) was a man of tremendous physical and intellectual strength. In any land and in any age he would have been a leader.” (Kalākaua, ROOK)

While still in his youth, Kamehameha proved his right to rule over all the islands by lifting the Naha Stone at Pinao Heiau in Pi‘ihonua, Hilo (c. 1773.) (ROOK)

By the time of Cook’s arrival (1778,) Kamehameha had become a superb warrior who already carried the scars of a number of political and physical encounters. The young warrior Kamehameha was described as a tall, strong and physically fearless man who “moved in an aura of violence.” (NPS)

The impress of his mind remains with his crude and vigorous laws, and wherever he stepped is seen an imperishable track. He was so strong of limb that ordinary men were but children in his grasp, and in council the wisest yielded to his judgment. He seems to have been born a man and to have had no boyhood. (Kalākaua)

He was always sedate and thoughtful, and from his earliest years cared for no sport or pastime that was not manly. He had a harsh and rugged face, less given to smiles than frowns, but strongly marked with lines indicative of self-reliance and changeless purpose. (Kalākaua)

He was barbarous, unforgiving and merciless to his enemies, but just, sagacious and considerate in dealing with his subjects. He was more feared and admired than loved and respected; but his strength of arm and force of character well fitted him for the supreme chieftaincy of the group, and he accomplished what no one else could have done in his day. (Kalākaua)

In 1790 (at the same time that George Washington was serving as the US’s first president,) the island of Hawaiʻi was under multiple rule; Kamehameha (ruler of Kohala, Kona and Hāmākua regions) successfully invaded Maui, Lanai and Molokai.

He sent an emissary to the famous kahuna (priest, soothsayer,) Kapoukahi, to determine how he could conquer all of the island of Hawaiʻi. According to Thrum, Kapoukahi instructed Kamehameha “to build a large heiau for his god at Puʻukoholā, adjoining the old heiau of Mailekini.”

It is estimated that the human chain from Pololū Valley to Puʻukohola had somewhere between 10,000-20,000 men carrying stones from Pololū Valley to Kawaihae. (NPS)

After completing the heiau in 1791, Kamehameha invited Keōua to come to Kawaihae to make peace. However, as Keōua was about to step ashore, he was attacked and killed by one of Kamehameha’s chiefs.

With Keōua dead, and his supporters captured or slain, Kamehameha became King of Hawaiʻi island, an event that according to prophesy eventually led to the conquest and consolidation of the islands under the rule of Kamehameha I.

It was the koa (warriors) of Hilo who supported Kamehameha in his early quest to unite Moku O Keawe. After gaining control of Moku O Keawe, Kamehameha celebrated the Makahiki in Hilo in 1794. (ROOK)

The village and area of Hilo was named by Kamehameha after a special braid that was used to secure his canoe. Kamehameha and Keōpūolani’s son, Liholiho (Kamehameha II) was born in Hilo (1797.) (ROOK)

Kamehameha’s great war fleet, Peleleu, that was instrumental in Kamehameha’s conquest, was built and based at Hilo (1796-1801). After uniting all of the islands under his rule in 1810, Hilo became Kamehameha’s first seat of government. (ROOK)

It was in Hilo that Kamehameha established his greatest law, the Kānāwai Māmalahoe (Law of the Splintered Paddle). (ROOK) Kamehameha’s Law of the Splintered Paddle of 1797 is enshrined in the State constitution, Article 9, Section 10: “Let every elderly person, woman and child lie by the roadside in safety”.

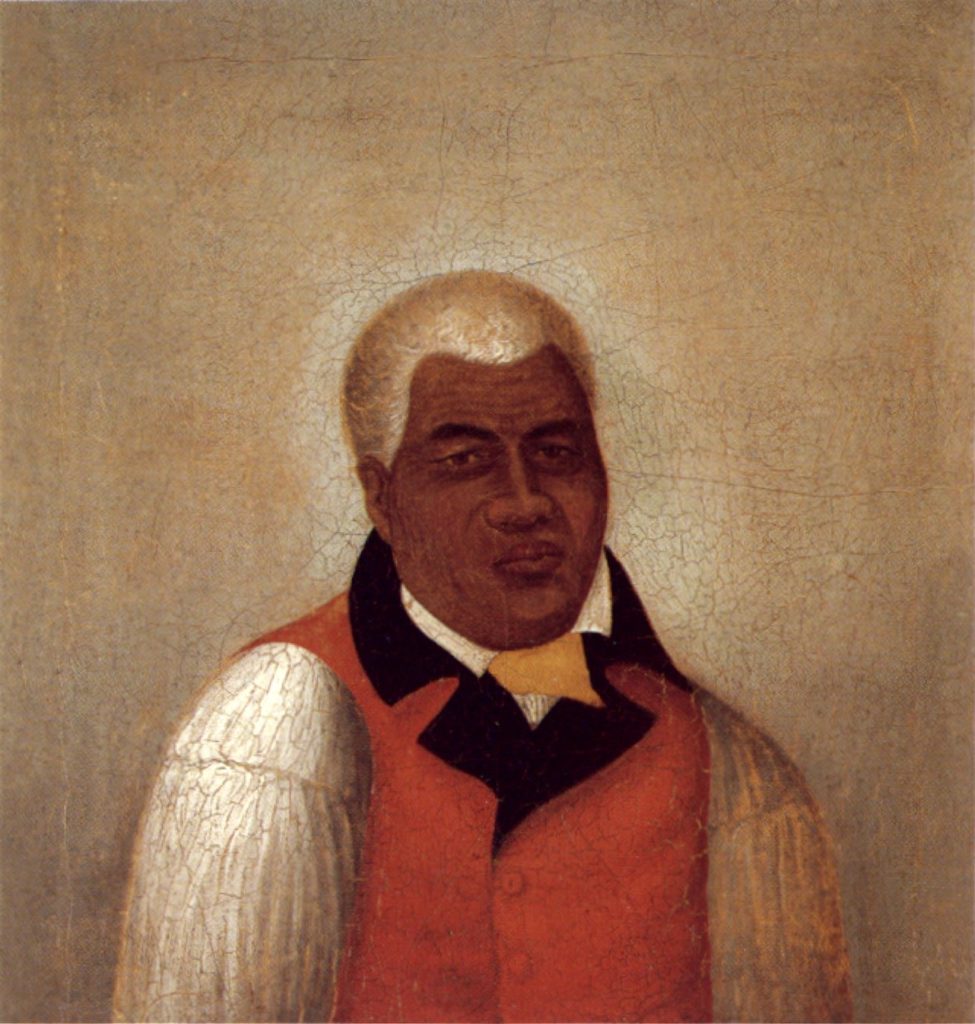

It has become a model for modern human rights law regarding the treatment of civilians and other non-combatants. Kānāwai Māmalahoe appears as a symbol of crossed paddles in the center of the badge of the Honolulu Police Department. The image shows Kamehameha as a young warrior (HerbKane.)