In 1837, Samuel Northrup Castle arrived in Honolulu as a missionary. He left Hawaiʻi for a short time, then returned as a businessman for the mission.

With Amos Cooke, he founded Castle & Cooke Company, in 1851 – it grew into being one of Hawaiʻi’s “Big Five” companies.

One of his ten children would surpass him as a businessman; James Bicknell Castle was born November 27, 1855 in Honolulu to Samuel and Mary (Tenney) Castle.

Harold Kainalu Long Castle was born July 3, 1886 in Honolulu, son of wealthy landowner James Bicknell Castle and Julia White, and grandson of Castle & Cooke founder Samuel Northrop Castle.

In 1917, Harold Castle purchased about 9,500-acres of land on the windward side of Oʻahu, in what became Kāneʻohe Ranch. Later acquisitions added several thousand acres of land, with holdings from Heʻeia to Waimanalo. The Castle fortune was built on ranching and dairying.

The family had land in Waikīkī, as well; it was formerly called Kalehuawehe. The surf break ‘Castles’ is named after the Castle family’s three-story beachfront home; they called it Kainalu. They later sold it to the Elks Club, who now use part of the site and lease the rest to the Outrigger Canoe Club.

With the widening and paving of Old Pali Road in 1921 (which helped to initiate the suburban commute across the Koʻolau,) the Castles realized that the Windward side of the island of Oʻahu was a beautiful place to live and could become a vibrant community. (The Pali Highway and its tunnels opened in 1959.)

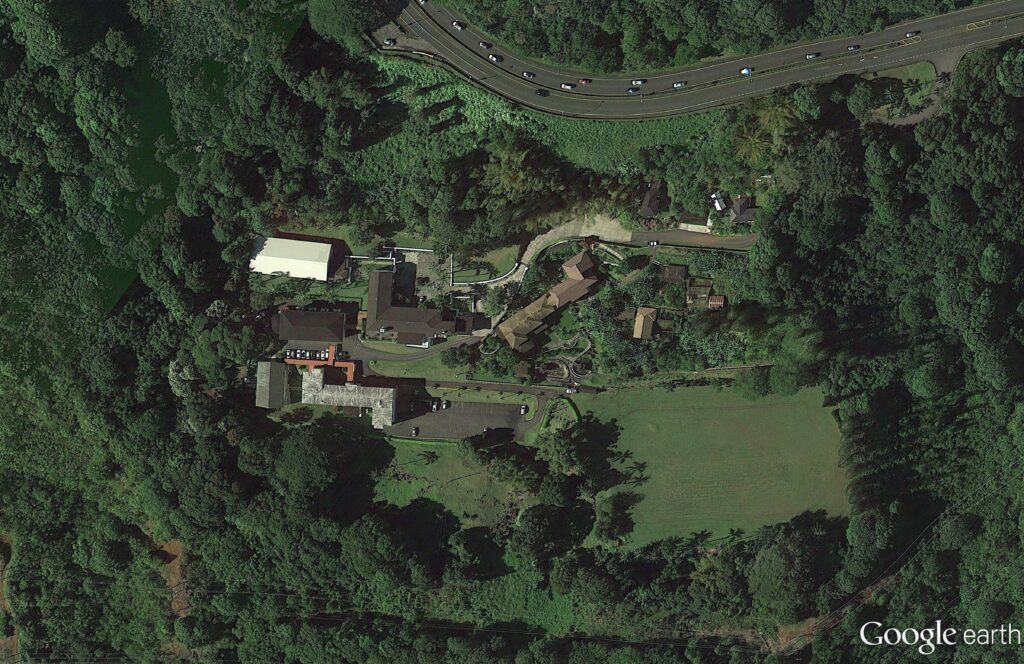

In 1927, Harold and his wife Alice Hedemann Castle built a home for themselves that overlooked much of their land holdings. It was just below the hairpin turn, below the Pali.

They called the home Palikū (Lit., vertical cliff.)

Architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue designed it (Goodhue’s other work included Los Angeles Central Public Library, the Nebraska State Capitol and Saint Thomas Church, New York City;) there were 27 rooms with ornamental ironwork, redwood beams, plumbing and electricity – one of the first buildings on the windward side of the island to have those amenities. (Brennan, Honolulu Advertiser)

In 1946, the Castles sold the 22-acre Palikū to the Catholic Church for the Saint Stephen Seminary (the seminary closed in 1970; it’s now the St. Stephen’s Diocesan Center (the driveway is makai, just below the scenic lookout at the hairpin turn.))

St. Stephen’s Seminary was shut down for a time after a mysterious occurrence in October 1946.

Some suggest the seminary was haunted; when one night there were methodical clicking and tapping sounds; invisible pressure on a person in bed; dishes, pots and pans strewn all over – they suggest it was “diabolical obsession.” Later, “I understand there was some kind of a blessing done,” said Bishop Joseph Ferrario, the retired bishop of Honolulu. (honoluluadvertiser)

After the seminary’s ultimate closure, the facility was transformed into a diocesan center housing various offices of the diocesan curia (a diocesan center (chancery) is the branch of administration which handles all written documents used in the official government of a Roman Catholic diocese.)

The former Castle home also serves as the residence of the Bishop of Honolulu, Clarence Richard Silva, popularly known as Larry Silva (born August 6, 1949), bishop of the Roman Catholic Church. He is the fifth Bishop of Honolulu, appointed by Pope Benedict XVI on May 17, 2005.

In 1962, Castle founded the Harold KL Castle Foundation. On his death in 1967, he bequeathed a sizeable portion of his real estate assets to the Foundation.

Throughout his life, Castle donated land for churches of all different denominations because he felt that churches would bring congregations, congregations would bring stability, and that would benefit the community that was growing around them.

Mr. Castle also donated land and money to Hawaii Loa College, Castle Hospital, ʻIolani School, Castle High School, Kainalu Elementary School and the Mōkapu peninsula land, which would become the Kāneʻohe Marine Corps Base.

His foundation has annually provided millions of dollars in support to worthy causes, a good chunk of it going to the windward side of Oʻahu.