by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

Did the Missionaries Really Stop Surfing in Hawaiʻi?

Open any book or read any article about surfing in Hawaiʻi and invariably there is a definitive statement that the missionaries “banned” and/or “abolished” surfing in Hawaiʻi.

OK, I am not being overly sensitive, here (being a descendent of Hiram Bingham, the leader of the first missionary group to Hawaiʻi;) actually, I believed the premise in the first line for a long time.

However, in taking a closer look into the matter, I am coming to a different conclusion.

First of all, the missionaries were guests in the Hawaiian Kingdom; they didn’t have the power to ban or abolish anything – that was the prerogative of the King and Chiefs.

Anyway, I agree; the missionaries despised the fact that Hawaiians typically surfed in the nude. They also didn’t like the commingling between the sexes.

So, before we go on, we need to agree, the issue at hand is surfing – not nudity and interactions between the sexes. In keeping this discussion on the sport and not sexuality, let’s see what the missionaries had to say about surfing.

I first looked to see what my great-great-great-grandfather, Hiram Bingham, had to say. He wrote a book, A Residence of Twenty-One Years in the Sandwich Islands, about his experiences in Hawaiʻi.

I word-searched “surf” (figuring I could get all word variations on the subject.) Here is what Bingham had to say about surfing (Bingham was leader of the 1st Company of missionaries to Hawaiʻi, arriving in 1820 – these are his words:)

“(T)hey resorted to the favorite amusement of all classes – sporting on the surf, in which they distinguish themselves from most other nations. In this exercise, they generally avail themselves of the surf-board, an instrument manufactured by themselves for the purpose.” (Bingham – page 136)

“The inhabitants of these islands, both male and female, are distinguished by their fondness for the water, their powers of diving and swimming, and the dexterity and ease with which they manage themselves, their surf-boards and canoes, in that element.” (Bingham – pages 136-137)

“The adoption of our costume greatly diminishes their practice of swimming and sporting in the surf, for it is less convenient to wear it in the water than the native girdle, and less decorous and safe to lay it entirely off on every occasion they find for a plunge or swim or surf-board race.” (Bingham – page 137)

“The decline or discontinuance of the use of the surf-board, as civilization advances, may be accounted for by the increase of modesty, industry or religion, without supposing, as some have affected to believe, that missionaries caused oppressive enactments against it. These considerations are in part applicable to many other amusements. Indeed, the purchase of foreign vessels, at this time, required attention to the collecting and delivering of 450,000 Ibs. of sandal-wood, which those who were waiting for it might naturally suppose would, for a time, supersede their amusements.” (Bingham – page 137)

Most people cite the first sentence in the above paragraph as admission by Bingham that the missionaries were the cause, but fail to quote the rest of the paragraph. In the remaining sentences of the same paragraph Bingham notes that with the growing demand to harvest sandalwood, there is less time for the Hawaiians to attend to their “amusements,” including surfing. These later words change the context of the prior.

Here is a bit of poetic support Bingham shows for the sport, “On a calm and bright summer’s day, the wide ocean and foaming surf, the peaceful river, with verdant banks, the bold cliff, and forest covered mountains, the level and fertile vale, the pleasant shade-trees, the green tufts of elegant fronds on the tall cocoanut trunks, nodding and waving, like graceful plumes, in the refreshing breeze; birds flitting, chirping, and singing among them, goats grazing and bleating, and their kids frisking on the rocky cliff, the natives at their work, carrying burdens, or sailing up and down the river, or along the sea-shore, in their canoes, propelled by their polished paddles that glitter in the sun-beam, or by a small sail well trimmed, or riding more rapidly and proudly on their surf-boards, on the front of foaming surges, as they hasten to the sandy shore, all give life and interest to the scenery.” (Bingham – pages 217-218)

Likewise, I did a word search for “surf” in the Levi Chamberlain journals and found the following (Chamberlain was the mission quartermaster in the 1830s:)

“The situation of Waititi (Waikīkī) is pleasant, & enjoys the shade of a large number of cocoanut & kou trees. The kou has large spreading branches & affords a very beautiful shade. There is a considerable extension of beach and when the surf comes in high the natives amuse themselves in riding on the surf-board.” (Chamberlain – Vol 2, page 18)

“The Chiefs amused themselves by playing on surfboards in the heart of Lahaina.” (Chamberlain – Vol 5, page 36)

Another set of Journals, belonging to Amos S. Cooke, also notes references to surfing (Cooke was in the 8th Company of missionaries arriving in 1837:)

“After dinner Auhea went with me, & the boys to bathe in the sea, & I tried riding on the surf. To day I have felt quite lame from it.” (Cooke – Vol 6, page 237) (Missionaries and their children also surfed.)

“This evening I have been reading to the smaller children from “Rollo at Play”–“The Freshet”. The older children are still reading “Robinson Crusoe”. Since school the boys have been to Waikiki to swim in the surf & on surf boards. They reached home at 7 o’clk. Last evening they went to Diamond Point – & did not return till 7 1/2 o’clock.” (Cooke – Vol 7, page 385)

“After dinner about three o’clock we went to bathe & to play in the surf. After we returned from this we paid a visit to the church which has lately been repaired with a new belfry & roof.” (Cooke – Vol 8, page 120)

James J Jarvis, in 1847, notes “Sliding down steep hills, on a smooth board, was a common amusement; but no sport afforded more delight than bathing in the surf. Young and old high and low, of both sexes, engaged in it, and in no other way could they show greater dexterity in their aquatic exercises. Multitudes could be seen when the surf was highest, pushing boldly seaward, with their surf-board in advance, diving beneath the huge combers, as they broke in succession over them, until they reached the outer line of breakers; then laying flat upon their boards, using their arms and legs as guides, they boldly mounted the loftiest, and, borne upon its crest, rushed with the speed of a race-horse towards the shore; from being dashed upon which, seemed to a spectator impossible to be avoided.” (Jarvis – page 39)

In 1851, the Reverend Henry T. Cheever observed surfing at Lāhaina, Maui and wrote about it in his book, Life in the Hawaiian Islands, The Heart of the Pacific As it Was and Is, “It is highly amusing to a stranger to go out to the south part of this town, some day when the sea is rolling in heavily over the reef, and to observe there the evolutions and rapid career of a company of surf-players. The sport (of surfing) is so attractive and full of wild excitement to the Hawaiians, and withal so healthy, that I cannot but hope it will be many years before civilization shall look it out of countenance, or make it disreputable to indulge in this manly, though it be dangerous, exercise.” (Cheever – pages 41-42)

Even Mark Twain notes surfing during his visit in 1866, “In one place we came upon a large company of naked natives, of both sexes and all ages, amusing themselves with the national pastime of surf-bathing. Each heathen would paddle three or four hundred yards out to sea, (taking a short board with him), then face the shore and wait for a particularly prodigious billow to come along; at the right moment he would fling his board upon its foamy crest and himself upon the board, and here he would come whizzing by like a bombshell! It did not seem that a lightning express train could shoot along at a more hair-lifting speed. I tried surf-bathing once, subsequently, but made a failure of it. I got the board placed right, and at the right moment, too; but missed the connection myself.–The board struck the shore in three quarters of a second, without any cargo, and I struck the bottom about the same time, with a couple of barrels of water in me..” (Mark Twain, Roughing It, 1880)

Obviously, surfing was never “banned” or “abolished” in Hawaiʻi.

These words from prominent missionaries and other observers note on-going surfing throughout the decades the missionaries were in Hawaiʻi (1820 – 1863.)

Likewise, their comments sound supportive of surfing, at least they were comfortable with it and they admired the Hawaiians for their surfing prowess (they are certainly not in opposition to its continued practice) – and Bingham seems to acknowledge that he realizes others may believe the missionaries curtailed/stopped it.

So, Bingham, who was in Hawaiʻi from 1820 to 1841, makes surprisingly favorable remarks by noting that Hawaiians were “sporting on the surf, in which they distinguish themselves from most other nations”. Likewise, Chamberlain notes they “amuse themselves in riding on the surf-board.”

Missionary Amos Cooke, who arrived in Hawaiʻi in 1837 – and was later appointed by King Kamehameha III to teach the young royalty in the Chief’s Childrens’ School – surfed himself (with his sons) and enjoyed going to the beach in the afternoon.

In the late-1840s, Jarvis notes, “Multitudes could be seen when the surf was highest, pushing boldly seaward, with their surf-board in advance”.

In the 1850s, Reverend Cheever notes, surfing “is so attractive and full of wild excitement to the Hawaiians, and withal so healthy”.

In the mid-1860s Mark Twain notes, the Hawaiians were “amusing themselves with the national pastime of surf-bathing. Each heathen would paddle three or four hundred yards out to sea, (taking a short board with him), then face the shore and wait for a particularly prodigious billow to come along; at the right moment he would fling his board upon its foamy crest and himself upon the board, and here he would come whizzing by like a bombshell!”

Throughout the decades, Hawaiians continued to surf and, if anything, the missionaries and others at least appreciated surfing (although they vehemently opposed nudity – likewise, today, nudity is frowned upon.)

And, using Cooke as an example, it is clear some of the missionaries and their families also surfed.

Of course, not everyone tolerated or supported surfing. Sarah Joiner Lyman notes in her book, “Sarah Joiner Lyman of Hawaii–her own story,” “You have probably heard that playing on the surf board was a favourite amusement in ancient times. It is too much practised at the present day, and is the source of much iniquity, inasmuch as it leads to intercourse with the sexes without discrimination. Today a man died on his surf board. He was seen to fall from it, but has not yet been found. I hope this will be a warning to others, and that many will be induced to leave this foolish amusement.” (Lyman – pages 63-63 – (John Clark))

“No Ka Molowa. Ua ’kaka loa ka molowa. Eia kekahi, o ka lilo loa o na kanaka i ka heenalu a me na wahine a me na keiki i ka lelekawa i ka mio.” (Ke Kumu Hawaii – January 31, 1838 – page 70 – (John Clark))

“Laziness. It is clear that they were lazy. The men would spend all their time surfing, and the women and children would spend all their time jumping and diving into the ocean.”

“No Ka Palaka. No ka palaka mai ka molowa, ka nanea, ka lealea, ka paani, ka heenalu,ka lelekawa, ka mio, ka heeholua, ka lelekowali; ka hoolele lupe, kela mea keia mea o ka palaka, oia ka mole o keia mau hewa he nui wale.” (Ke Kumu Hawaii – January 31, 1838 – page 70 – (John Clark))

“Indifference. Indifference is the source of laziness, relaxation, enjoyment, play, surfing, cliff jumping, diving, sledding, swinging, kite flying, and all kinds of indifferent activities; indifference is the root of these many vices.”

Let’s look some more – could something else be a cause for the apparent reduction of surfers in the water? What about affects the socio-economic and demographic changes may have had on the peoples’ opportunity to surf?

Remember, in 1819, prior to the arrival of the missionaries, Liholiho abolished the kapu system. This effectively also cancelled the annual Makahiki celebrations and the athletic contests and games associated with them.

Likewise, the Chiefs were distracted by new Western goods and were directing the commoners to work at various tasks that took time away from other activities, including surfing.

Between 1805 and 1830, the common people were displaced from much of their traditional duties (farming and fishing) and labor was diverted to harvesting sandalwood.

Between 1819 and 1859, whaling was the economic mainstay in the Islands. Ships re-provisioned in Hawaiʻi, and Hawaiians grew the crops for these needs: fresh vegetables, fresh fruit, cattle, white potatoes and sugar.

With the start of a successful sugar plantation in 1835, Hawai‘i’s economy turned toward sugar and saw tremendous expansion in the decades between 1860 and 1880.

From the time of contact (1778,) Hawaiians were transitioning from a subsistence economy to a market economy and the people were being employed to work at various industries. (Even today’s surfers prefer to surf all the time, but in many cases obligations at work means you can’t surf all the time.)

In light of the demands these industries have in distracting people away from their recreational pursuits, let’s look at the Hawaiian population changes.

Since contact in 1778, the Hawaiian population declined rapidly after exposure to a host of diseases for which they had no immunity. In addition, many Hawaiians moved away or worked overseas.

The Hawaiian population in 1778 is estimated to have been approximately 300,000 (estimates vary; some as high as 800,000 to 1,000,000; but many writers suggest the 300,000 estimate – a higher 1778 estimate more dramatically illustrates the change in population.)

Whatever the ‘contact’ starting point, by 1860 the Islands’ population drastically declined to approximately 69,800. Fewer people overall means fewer people in the water and out surfing.

My immediate reaction in reading what the missionaries and others had to say is that the purported banning and/or opposition to surfing may be more urban legend, than fact.

It is easy to blame the missionaries, but there doesn’t seem to be basis to do so.

Rather, I tend to agree with what my relative, missionary Hiram Bingham, had to say (rather poetically, to my surprise,) “On a calm and bright summer’s day, the wide ocean and foaming surf … the green tufts of elegant fronds on the tall cocoanut trunks, nodding and waving, like graceful plumes, in the refreshing breeze … the natives … riding more rapidly and proudly on their surf-boards, on the front of foaming surges … give life and interest to the scenery.”

Surf’s up – let’s go surfing!

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of American Protestant missionaries from the northeast US set sail on the Thaddeus for the Sandwich Islands (now known as Hawai‘i.) There were seven American couples sent by the ABCFM in this first company.

These included two Ordained Preachers, Hiram Bingham and his wife Sybil and Asa Thurston and his wife Lucy; two Teachers, Mr. Samuel Whitney and his wife Mercy and Samuel Ruggles and his wife Mary; a Doctor, Thomas Holman and his wife Lucia; a Printer, Elisha Loomis and his wife Maria; and a Farmer, Daniel Chamberlain, his wife and five children.

By the time the Pioneer Company arrived, Kamehameha I had died and the centuries-old kapu system had been abolished; through the actions of King Kamehameha II (Liholiho,) with encouragement by former Queens Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani (Liholiho’s mother,) the Hawaiian people had already dismantled their heiau and had rejected their religious beliefs.

One of the first things the missionaries did was begin to learn the Hawaiian language and create an alphabet for a written format of the language. Their emphasis was on teaching and preaching.

The first mission station was at Kailua-Kona, where they first landed in the Islands, then the residence of the King (Liholiho, Kamehameha II;) Asa and Lucy Thurston manned the mission, there.

Liholiho was Asa Thurston’s first pupil. His orders were that “none should be taught to read except those of high rank, those to whom he gave special permission, and the wives and children of white men.”

James Kahuhu and John ʻlʻi were two of his favorite courtiers, whom he placed under Mr. Thurston’s instruction in order that he might judge whether the new learning was going to be of any value. (Alexander, The Friend, December 1902)

In 1820, Missionary Lucy Thurston noted in her Journal, “The king (Liholiho, Kamehameha II) brought two young men to Mr. Thurston, and said: ‘Teach these, my favorites, (John Papa) Ii and (James) Kahuhu. It will be the same as teaching me. Through them I shall find out what learning is.’”

“To do his part to distinguish and make them respectable scholars, he dressed them in a civilized manner. They daily came forth from the king, entered the presence of their teacher, clad in white, while his majesty and court continued to sit in their girdles.”

“Although thus distinguished from their fellows, in all the beauty and strength of ripening manhood, with what humility they drank in instruction from the lips of their teacher, even as the dry earth drinks in water!”

“After an absence of some months, the king returned, and called at our dwelling to hear the two young men, his favorites, read. He was delighted with their improvement, and shook Mr. Thurston most cordially by the hand – pressed it between both his own – then kissed it.” (Lucy Thurston)

Kahuhu was among the earliest of those associated with the chiefs to learn both spoken and written words. Kahuhu then became a teacher to the chiefs.

In April or May 1821, the King and the chiefs gathered in Honolulu and selected teachers to assist Mr Bingham. James Kahuhu, John ʻĪʻi, Haʻalilio, Prince Kauikeaouli were among those who learned English. (Kamakau)

On October 7, 1829, it seems that Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) set up a legislative body and council of state when he prepared a definite and authoritative declaration to foreigners and each of them signed it. (Frear – HHS) Kahuhu was one of the participants.

King Kamehameha III issued a Proclamation “respecting the treatment of Foreigners within his Territories.” It was prepared in the name of the King and the Chiefs in Council: Kauikeaouli, the King; Gov. Boki; Kaʻahumanu; Gov. Adams Kuakini; Manuia; Kekūanāoʻa; Hinau; ʻAikanaka; Paki; Kīnaʻu; John ʻIʻi and James Kahuhu.

In part, he states, “The Laws of my Country prohibit murder, theft, adultery, fornication, retailing ardent spirits at houses for selling spirits, amusements on the Sabbath Day, gambling and betting on the Sabbath Day, and at all times. If any man shall transgress any of these Laws, he is liable to the penalty, – the same for every Foreigner and for the People of these Islands: whoever shall violate these Laws shall be punished.”

It continues with, “This is our communication to you all, ye parents from the Countries whence originate the winds; have compassion on a Nation of little Children, very small and young, who are yet in mental darkness; and help us to do right and follow with us, that which will be for the best good of this our Country.”

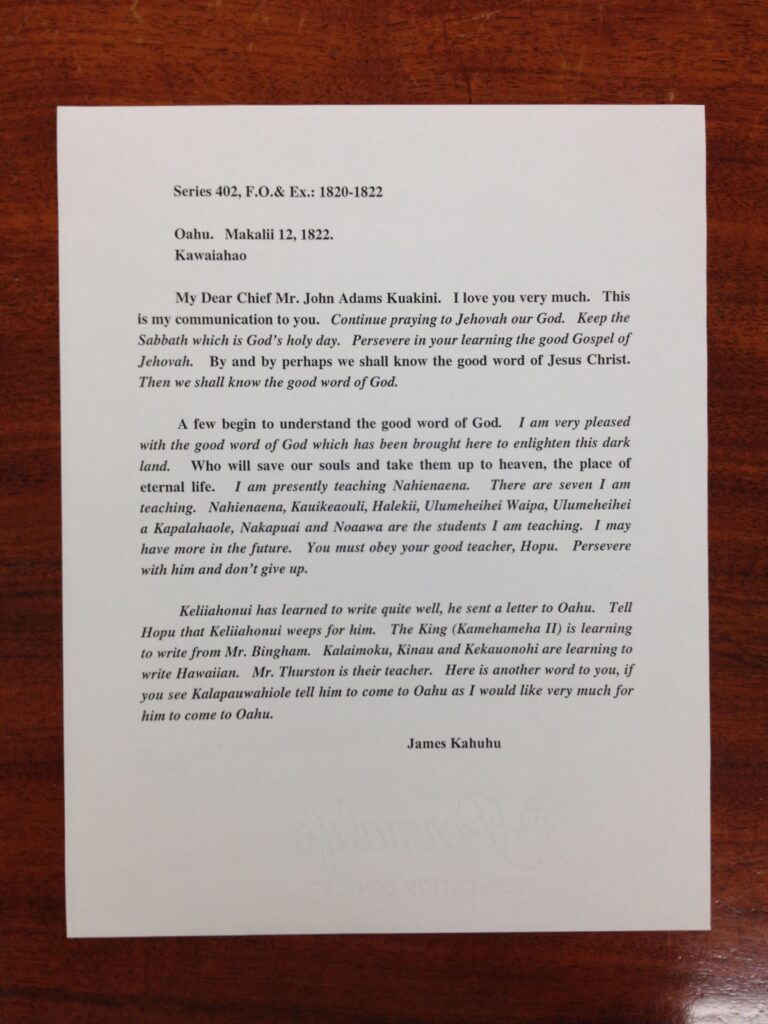

The Hawaiʻi State Archives is the repository of significant historic documents for Hawaiʻi; reportedly, the oldest Hawaiian language document in its possession is a letter written by James Kahuhu.

Writing to Chief John Adams Kuakini, Kahuhu’s letter was partially in English and partially Hawaiian (at that time, Kuakini was learning both English and written Hawaiian.)

Below is a transcription of Kahuhu’s letter. (HSA)

Oahu. Makaliʻi 12, 1822.

Kawaiahaʻo.

My Dear Chief Mr. John Adams Kuakini. I love you very much. This is my communication to you. Continue praying to Jehovah our God. Keep the Sabbath which is God’s holy day. Persevere in your learning the good Gospel of Jehovah. By and by perhaps we shall know the good word of Jesus Christ. Then we shall know the good word of God.

A few begin to understand the good word of God. I am very pleased with the good word of God which has been brought here to enlighten this dark land. Who will save our souls and take them up to heaven, the place of eternal life. I am presently teaching Nahiʻenaʻena. I am teaching seven of them. Nahienaena, Kauikeaouli, Halekiʻi, Ulumāheihei Waipa, Ulumāheihei a Kapalahaole, Nakapuai and Noaʻawa are the students I am teaching. I may have more in the future. You must obey your good teacher, Hopu. Persevere with him and don’t give up.

Keliʻiahonui has learned to write quite well, he sent a letter to Oahu. Tell Hopu that Keliʻiahonui misses him. The King is learning to write from Mr. Bingham. Kalanimōku, Kīnaʻu and Kekauōnohi are learning to write Hawaiian. Mr. Thurston is their teacher. Here is another word to you, if you see Kalapauwahiole tell him to come to Oahu as I would like very much for him to come to Oahu.

James Kahuhu

(Makaliʻi was the name of a month: December on Hawai‘i, April on Moloka’i, October on Oʻahu. (Malo))

The image shows the first page of the Kahuhu letter to Kuakini (HSA.)

by Peter T Young 1 Comment

The Era of Good Feelings began with a burst of nationalistic fervor. The economic program adopted by Congress, including a national bank and a protective tariff, reflected the growing feeling of national unity.

The Supreme Court promoted the spirit of nationalism by establishing the principle of federal supremacy. Industrialization and improvements in transportation also added to the sense of national unity by contributing to the nation’s economic strength and independence and by linking the West and the East together.

But this same period also witnessed the emergence of growing factional divisions in politics, including a deepening sectional split between the North and South.

A severe economic depression between 1819 and 1822 provoked bitter division over questions of banking and tariffs. Geographic expansion exposed latent tensions over the morality of slavery and the balance of economic power. (University of Houston, Digital History)

The Panic of 1819 and the accompanying Banking Crisis of 1819 were economic crises in the US that some historians refer to it as the first Great Depression.

The growth in trade that followed the War of 1812 came to an abrupt halt. Unemployment mounted, banks failed, mortgages were foreclosed, and agricultural prices fell by half. Investment in western lands collapsed.

The panic was frightening in its scope and impact. In New York State, property values fell from $315 million in 1818 to $256 million in 1820. In Richmond, Virginia, property values fell by half. In Pennsylvania, land values plunged from $150 an acre in 1815 to $35 in 1819. In Philadelphia, 1,808 individuals were committed to debtors’ prison. In Boston, the figure was 3,500.

For the first time in American history, the problem of urban poverty commanded public attention. In New York in 1819, the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism counted 8,000 paupers out of a population of 120,000.

Fifty thousand people were unemployed or irregularly employed in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, and one foreign observer estimated that half a million people were jobless nationwide.

The downswing spread like a plague across the country. In Cincinnati, bankruptcy sales occurred almost daily. In Lexington, Kentucky, factories worth half a million dollars were idle. Matthew Carey, a Philadelphia economist, estimated that 3 million people, one-third of the nation’s population, were adversely affected by the panic.

In 1820, John C. Calhoun (later to become US Vice President) commented: “There has been within these two years an immense revolution of fortunes in every part of the Union; enormous numbers of persons utterly ruined; multitudes in deep distress.”

The Panic of 1819 and the Banking Crisis left many people destitute. People lost their land due to their inability to pay off their mortgages. United States factory owners also had a difficult time competing with earlier established factories in Europe.

The United States did not fully recover from the Banking Crisis and the Panic of 1819 until the mid-1820s. These economic problems contributed immensely to the rise of Andrew Jackson. (Ohio History Central)

In the Islands …

The ʻaikapu is a belief in which males and females are separated in the act of eating; males being laʻa or ‘sacred,’ and females haumia or ‘defiling’ (by virtue of menstruation.)

Since, in this context, eating is for men a sacrifice to the male akua (god) Lono, it must be done apart from anything defiling, especially women. Thus, men prepared the food in separate ovens, one for the men and another for the women, and built separate eating houses for each.

The kahuna suggested that the new ʻaikapu religion should also require that four nights of each lunar month be set aside for special worship of the four major male akua, Ku, Lono, Kane and Kanaloa. On these nights it was kapu for men to sleep with their wahine. Moreover, they should be at the heiau (temple) services on these nights.

Under ʻaikapu, certain foods, because of their male symbolism, also are forbidden to women, including pig, coconuts, bananas, and some red fish. (Kameʻeleihiwa)

“The custom of the tabu upon free eating was kept up because in old days it was believed that the ruler who did not proclaim the tabu had not long to rule. If he attempted to continue the practice of free eating he was quickly disinherited.”

“The tabu of the chief and the eating tabu were different in character. The eating tabu belonged to the tabus of the gods; it was forbidden by the god and held sacred by all. It was this tabu that gave the chiefs their high station.” (Kamakau)

If a woman was clearly detected in the act of eating any of these things, as well as a number of other articles that were tabu, which I have not enumerated, she was put to death. (Malo) (Sometimes surrogates paid the penalty.)

But there were times ʻaikapu prohibitions were not invoked and women were free to eat with men, as well as enjoy the forbidden food – ʻainoa (to eat freely, without regarding the kapu.)

“In old days the period of mourning at the death of a ruling chief who had been greatly beloved was a time of license. The women were allowed to enter the heiau, to eat bananas, coconuts and pork, and to climb over the sacred places.” (Kamakau)

“Free eating followed the death of the ruling chief; after the period of mourning was over the new ruler placed the land under a new tabu following old lines. (Kamakau)

Following the death of Kamehameha I in 1819, Liholiho assented and became ruling chief with the title Kamehameha II and Kaʻahumanu, co-ruler with the title kuhina nui.

Kaʻahumanu, made a plea for religious tolerance, saying: “If you wish to continue to observe (Kamehameha’s) laws, it is well and we will not molest you. But as for me and my people we intend to be free from the tabus.”

“We intend that the husband’s food and the wife’s food shall be cooked in the same oven and that they shall be permitted to eat out of the same calabash. We intend to eat pork and bananas and coconuts. If you think differently you are at liberty to do so; but for me and my people we are resolved to be free. Let us henceforth disregard tabu.”

Keōpūolani, another of Kamehameha I’s wives, was the highest ranking chief of the ruling family in the kingdom during her lifetime. She was a niʻaupiʻo chief, and looked upon as divine; her kapu, equal to those of the gods. (Mookini) Giving up the ʻaikapu (and with it the kapu system) meant her traditional power and rank would be lost.

Never-the-less, symbolically to her son, Liholiho, the new King of the Islands, she put her hand to her mouth as a sign for free eating. Then she ate with Kauikeaouli, and it was through her influence that the eating tabu was freed. Liholiho permitted this, but refrained from any violation of the kapu himself. (Kuykendall)

Keōpūolani ate coconuts which were tabu to women and took food with the men, saying, “He who guarded the god is dead, and it is right that we should eat together freely.” (Kamakau)

The ʻainoa following Kamehameha’s death continued and the ʻaikapu was not put into place – effectively ending the centuries-old kapu system.

Coming of the American Protestant Missionaries – 1819

On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of missionaries from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) from the northeast United States, set sail from Boston on the Thaddeus for Hawai‘i.

The Prudential Committee of the ABCFM in giving instructions to the pioneers of 1819 said: “Your mission is a mission of mercy, and your work is to be wholly a labor of love. …”

“Your views are not to be limited to a low, narrow scale, but you are to open your hearts wide, and set your marks high. You are to aim at nothing short of covering these islands with fruitful fields, and pleasant dwellings and schools and churches, and of Christian civilization.” (The Friend)

“Oct. 23, 1819. – This day by the good providence of God, I have embarked on board the brig Thaddeus (Blanchard master) for the Sandwich Islands to spread the gospel of Christ among the heathens.” (The term ‘heathen’ (without the knowledge of Jesus Christ and God) was a term in use at the time (200-years ago.))

“At 8 oclock took breakfast with the good Mr. Homer; at 11, gave the parting hand toward our dear friends on shore, & came on board accompanied by the Prudential Com. Mr. and Mrs. Dwight and some others.” (Samuel Whitney)

“That day week (the 23d), a great crowd of friends, acquaintances, and strangers, gathered on Long Wharf, for farewell religious exercises. The assembly united in singing the hymn, ‘Blest be the tie that binds.’”

“Dr. Worcester, in fervent prayer, commended the band to the God of missions; and Thomas Hopoo made a closing address. The two ordained brethren, assisted by an intimate friend, & then with perfect composure sang the lines, ‘When shall we all meet again?’”

“A fourteen-oared barge, politely offered by the commanding officer of the ‘Independence’ 74, was in waiting; the members of the mission took leave of their weeping friends, and were soon on board the brig ‘Thaddeus,’ Capt. Blanchard, which presently weighed anchor, dropped down the harbor, and the next day, with favoring tide and breeze, put out to sea. (Thompson)

After 164-days at sea, on April 4, 1820, the Thaddeus arrived and anchored at Kailua-Kona on the Island of Hawaiʻi. Hawai‘i’s “Plymouth Rock” is about where the Kailua pier is today.

By the time the Pioneer Company arrived, Kamehameha I had died and the centuries-old kapu system had been abolished; through the actions of King Kamehameha II (Liholiho,) with encouragement by former Queens Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani (Liholiho’s mother,) the Hawaiian people had already dismantled their heiau and had rejected their religious beliefs.

Over the course of a little over 40-years (1820-1863 – the “Missionary Period”), about 184-men and women in twelve Companies from New England served in Hawaiʻi to carry out the mission of the ABCFM in the Hawaiian Islands.

Collaboration between the Hawaiians and the American Protestant missionaries resulted in the

First Whalers to Hawai‘i – 1819

Edmond Gardner, captain of the New Bedford whaler Balaena (also called Balena,) and Elisha Folger, captain of the Nantucket whaler Equator, made history in 1819 when they became the first American whalers to visit the Sandwich Islands (Hawai‘i.)

“I had one man complaining with scurvy and fearing I might have more had made up my mind to go to the Sandwich Islands. I had prepared my ship with all light sails when I met the Equator.”

“I informed him of my intention. He thought it was too late to go off there and get in time on the West Coast of Mexico. I informed Folger what my determination was.”

“I gave orders in the morning to put the ship on a WSW course putting on all sail. In a short time after the morning, I discovered he was following. We made the best of our way to the Sandwich Islands where we arrived in six-teen days, had a pleasant passage to the Islands and arrived at Hawaii 19th 9 Mo 1819.“ (Gardner Journal)

A year later, Captain Joseph Allen discovered large concentrations of sperm whales off the coast of Japan. His find was widely publicized in New England, setting off an exodus of whalers to this area.

These ships might have sought provisions in Japan, except that Japanese ports were closed to foreign ships. So when Captain Allen befriended the missionaries at Honolulu and Lahaina, he helped establish these areas as the major ports of call for whalers. (NPS)

“The importance of the Sandwich Islands to the commerce of the United States, which visits these seas, is, perhaps, more than has been estimated by individuals, or our government been made acquainted with.”

“To our whale fishery on the coast of Japan they are indispensably necessary: hither those employed in this business repair in the months of April and May, to recruit their crews, refresh and adjust their ships; they then proceed to Japan, and return in the months of October and November.”

“The importance of the Sandwich Islands to the commerce of the United States, which visits these seas, is, perhaps, more than has been estimated by individuals, or our government been made acquainted with.”

“To our whale fishery on the coast of Japan they are indispensably necessary: hither those employed in this business repair in the months of April and May, to recruit their crews, refresh and adjust their ships; they then proceed to Japan, and return in the months of October and November.” (John Coffin Jones Jr, US Consulate, Sandwich Islands, October 30th, 1829)

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

“Mid-Pacific Institute is unqualifiedly Christian. It is the fruitage of missionary enterprise and cherishes the legacy which the mission fathers and mothers have passed on to it.”

“Even possible educational advantage such as good teachers, supervised study, small classes, and an uplifting home environment, are afforded its pupils but its real claim for its right to exist and receive the support of its friends is the emphasis it places upon Christian character-building.”

“The land, buildings and endowment are the gifts of Christian men and women; the love, vision and faith which gave it birth are Christian; its purpose and ideals are Christian. Many of the students come from non-Christian homes and their first introduction to the life and teachings of Jesus Christ is received here.”

“All students attend Sunday School and Church services in the city churches. Daily chapel services are held in each department while live Christian Endeavor and Mission societies give the students ample opportunity for self-expression.”

“Mid-Pacific Institute owes its birth to the vision, enthusiasm and tireless energy of Francis W Damon. With an abiding faith in the need of such an institution he persistently and patiently urged its claims until others caught his spirit and in 1905 the Hawaiian Board of Missions sanctioned it and appointed the first Board of Managers.”

“Unlike most institutions Mid-Pacific came into life full-grown, for it was made up of schools which had already made valuable contributions to the education of Hawaii’s youth – Kawaiahaʻo Seminary for girls and Mills School for boys.”

“Mills School came into being through the efforts of Mr. Damon, who was then Superintendent of Chinese work for the Hawaiian Board, to make it possible for worthy Chinese boys from the country districts to find both a school and a home.” (John Hopwood, Mid-Pacific President, April 1923)

Kawaiaha‘o Female Seminary

In 1863, missionaries Mr. and Mrs. Luther Gulick started a boarding school for girls in Kaʻū. This was continued at Waiohinu for two years, but was moved to Oʻahu. The Gulicks’ school was established “to teach the principles of Christianity, domestic science, and the ways and usages of western civilization.”

Mrs. Gulick felt that her opportunity had come. No one else could begin the school. She had been longing for more missionary work to do, and now the door was open. She writes: “Opened school this morning with eight scholars.” (The Friend)

In 1867, the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society (HMCS – an organization consisting of the children of the missionaries and adopted supporters) decided to support a girls’ boarding school. An early advertisement (April 13, 1867) notes it was called Honolulu Female Academy.

It started with boarders and day students, but after 1871 it has been exclusively a boarding school. “Under her patient energy and tact, with the help of her assistants, it prospered greatly, and became a success.” (Coan)

At first the school was designed to prepare Hawaiian girls to become ‘suitable’ wives for men who were at the same time preparing to become missionaries and work in the South Seas.

This objective took the back seat to industrial education as new industrial departments were added. This included sewing, washing and ironing, dressmaking, domestic arts and nursing.

Kawaiahaʻo Seminary continued to grow over the years and the student body was drawn from all over the islands and from all racial groups; some of the scholars included members of the royal family. (Attendance averaged over a hundred per year, with the largest number of pupils appears to have been in 1889, when 144 names were on the rolls.)

Mills School for Boys (Mills Institute)

Mills School for Boys was started as a small downtown missionary school in 1892, by Mr. and Mrs. Francis W Damon (descendant of missionary Rev Samuel C Damon), who took into their home a number of Chinese boys with the aim of giving them a Christian education.

Frank Damon, who was born in Hawai‘i, toured the world with Henry Carter, and married Mary Happer, a missionary’s daughter, who had been born and reared in Kuangzhou, China, and spoke fluent Cantonese. Frank Damon was appointed by the Hawaiian Evangelical Association as the superintendent of Chinese work in 1881. (Fan)

“(S)ix Chinese youths fired with the passion for knowledge, knocked at the door of the Damon home in Honolulu and asked to be taken in and taught. A room was found, instruction began, the six multiplied slowly until they have become more than four hundred who have found Mills a blessed home of light and truth.”

“The influence of this school upon our Territory can never be told. Its graduates are found in all walks of life, occupying positions of influence here, on the Pacific coast and in China.” (The Friend, October 1905)

Bringing The Two Together

Kawaiahaʻo Seminary and Mills School had much in common – they were home schools; founded by missionary couples; and had boarding of students.

With these commonalities, in 1905, a merger of the two was suggested, forming a co-educational institution in the same facility.

In order to accommodate a combined school, the Hawaiian Board of Foreign Missions purchased the Kidwell estate, about 35-acres of land in Mānoa valley.

Through gifts by GN Wilcox, JB Atherton and others, on May 31, 1906, a ceremony was held in Mānoa Valley for the new school campus – just above what is now the University of Hawaiʻi (the UH campus was not started in the Mānoa location until 1912.)

By 1908, the first building was completed, and the school was officially operated as Mid-Pacific Institute, consisting of Kawaiahaʻo School for Girls and Damon School for Boys.

Initially, while the two schools moved to the same campus, they essentially went their separate ways there for years; they had different curricula, different academic standards and different policies.

Finally, in the fall of 1922, a new coeducational plan went into effect – likewise, ‘Mills’ and ‘Kawaiahaʻo’ were dropped, and by June 1923, Mid-Pacific became the common, shared name.

In November 2003, the school decided to terminate its on-campus dormitory (which had existed since 1908). Epiphany School, established in 1937 as a small mission school by the Episcopal Church of the Epiphany, merged with Mid-Pacific Institute in 2004.