The legend of King Arthur (Le Morte Darthur, Middle French for “the Death of Arthur” (published in 1485)) speaks of King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot and the Knights of the Round Table (and foresees “Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone is the rightwise born king of all England.”)

Many tried; many failed.

Legendary Arthur later became the king of England when he removes the fated sword from the stone. Legendary Arthur goes on to win many battles due to his military prowess and Merlin’s counsel; he then consolidates his kingdom. (The historical basis for the King Arthur legend has long been debated by scholars.)

In Hawaiʻi, a couple legends and prophecies relate to a stone, Naha Pōhaku (the Naha Stone.)

Its weight is estimated to be two and one-half tons (5,000-pounds.) The stone was originally located in the Wailua River, Kauai; it was brought to Hilo by chief Makaliʻinuikualawaiea on his double canoe and placed in front of Pinao Heiau. (NPS)

The stone was reportedly endowed with great powers and had the peculiar property of being able to determine the legitimacy of all who claimed to be of the royal blood of the Naha rank (the product of half-blood sibling unions.)

As soon as a boy of Naha stock was born, he was brought to the Naha Stone and was laid upon it – one faint cry would bring him shame. However, if the infant had the virtue of silence, he would be declared by the kahuna to be of true Naha descent, a royal prince by right and destined to become a brave and fearless soldier and a leader of his fellow men. (NPS)

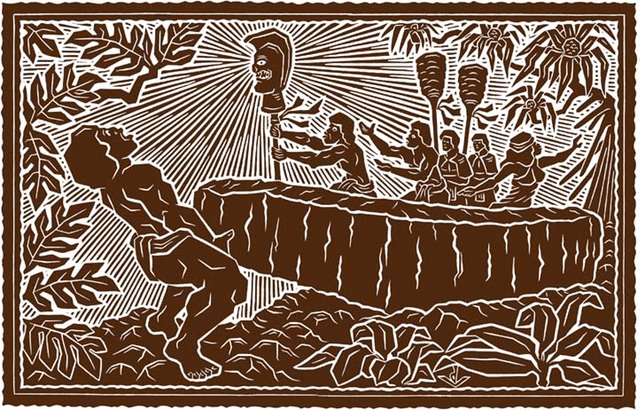

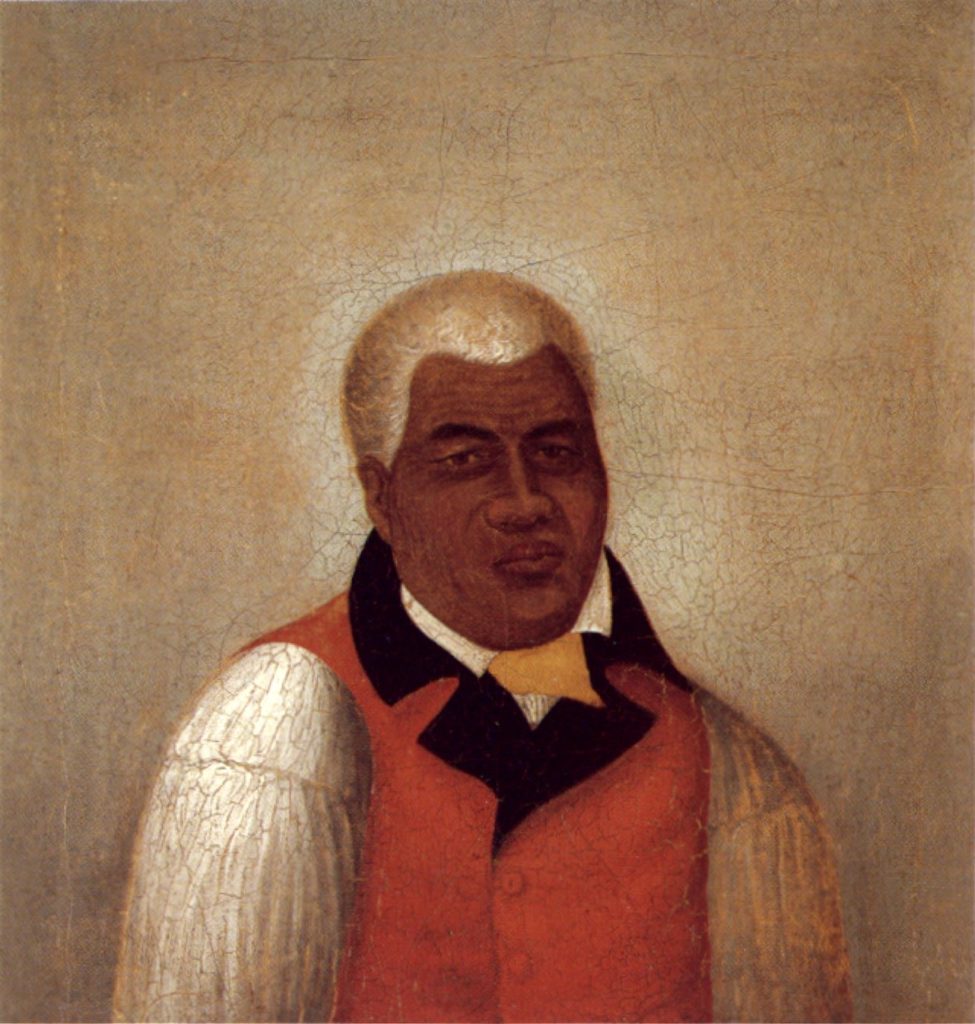

In another instance, Kamehameha traveled from Kohala to Hilo with Kalaniwahine a prophetess, who advised him that there was a deed he must do. Although not of Naha lineage, Kamehameha came to conquer the Naha Stone.

Kalaniwahine proclaimed that if he succeeded in moving Naha Pōhaku, that he would move the whole group of Islands. If he changed the foundations of Naha Pōhaku from its resting place, he would conquer the whole group and he would prosper and his people would prosper.

Kamehameha said, “He Naha oe, a he Naha hoi kou mea e neeu ai. He Niau-pio hoi wau, ao ka Niau-pio hoi o ka Wao.” (”You are a Naha, and it will be a Naha who will move you. I am a Niaupio, the Niaupio of the Forest.”)

With these words did Kamehameha put his shoulders up to the Naha Stone, and flipped it over, being this was a stone that could not be moved by five men. (Hoku o Hawaiʻi, November 1, 1927)

When Kamehameha gripped the stone and leaned over it, he leaned, great strength came into him, and he struggled yet more fiercely, so that the blood burst from his eyes and from the tips of his fingers, and the earth trembled with the might of his struggling, so that they who stood by believed that an earthquake came to his assistance. (NPS)

The stone moved and he raised it on its side.

And, the rest of the history of the Islands has been pretty clear about the fulfillment of the prophecy and unification of the Islands under Kamehameha.

The Naha Stone is in front of Hilo Public Library at 300 Waiānuenue Avenue between Ululani and Kapiʻolani Street (the larger of the two stones there.)

The upright stone sitting to the makai side of the Naha Stone is associated with the Pinao Heiau, one of several that once stood in Hilo. Some of the stones that built the first Saint Joseph church and other early stone buildings in town likely came from Pinao heiau. (Zane)