Wigglesworth Dole (born on November 17, 1779) married Elizabeth Haskell (born August 30, 1788. Among their children, they had two sons, Daniel Dole (born September 9, 1808) and Nathan Dole (born May 8, 1811).

Daniel had a son, Sanford Ballard Dole; Nathan had a son Charles Fletcher Dole – Charles’ first cousin was Sanford Ballard Dole. Charles had a son James Drummond Dole. James and Sanford were first cousins once removed (separated by one generation).

Wigglesworth Dole worked as a cabinet maker and kept a small farm, while serving as Deacon of a Congregational Church. Daniel Dole became a Protestant missionary to Hawai‘i. Nathan Dole was ordained as minister of the first Congregational Church in Brewer, Maine. Charles Dole was a Unitarian minister.

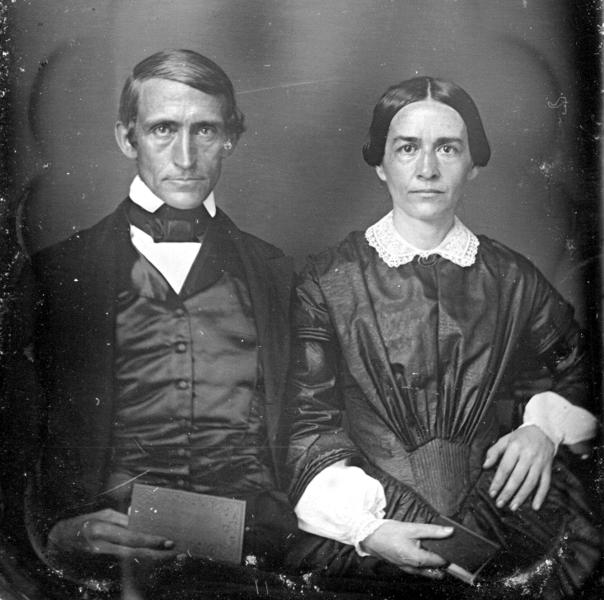

Daniel Dole graduated from Bowdoin College in 1836 and Bangor Theological Seminary in 1839, and then married Emily Hoyt Ballard (1807-1844,) October 2, 1840 in Gardiner, Maine. They were in the Ninth Company of missionaries to Hawai‘i and arrived in May 1841.

The education of their children was a concern of missionaries in Hawai‘i. There were two major dilemmas, (1) there were a limited number of missionary children and (2) existing schools (which the missionaries taught) served adult Hawaiians (who were taught from a limited curriculum in the Hawaiian language.)

During the first 21-years of the missionary period (1820-1863,) no fewer than 33 children were shipped off to the continent by their parents. (Seven-year-old Sophia Bingham, the first Caucasian girl born on Oʻahu, daughter of Hiram and Sybil, was sent to the continent in 1828. She is my great-great-grandmother.)

Resolution 14 of the 1841 General Meeting of the Sandwich Islands Mission changed that; it established a school for the children of the missionaries (May 12, 1841.) A subsequent Resolution noted “That Mr (Daniel) Dole be located at Punahou, as teacher for the Children of the Mission.”

Daniel Dole resigned from Punahou in 1855 to become the pastor and teacher at Kōloa, Kauai. There, he started the Dole School that later became Kōloa School, the first public school on Kauai. Like Punahou, it filled the need to educate mission children.

Dole Street, laid out in 1880 and part of the development of the lower Punahou pasture was named after Daniel Dole (other nearby streets were named after other Punahou presidents.)

Sanford Dole, son of Daniel, was born at Punahou School. Sanford avoided the ministry and from 1866 to 1868 he studied at Williams College in Williamstown, MA, and studied law in Boston. He became a lawyer in Honolulu in 1869.

In 1884 and 1886 Sanford Dole was elected to the Hawai‘i legislature. In 1887 he was appointed an associate justice of the Hawaiian Supreme Court.

Sanford Dole desired the annexation of Hawai‘i by the US so that Hawaiian sugar planters could favorably compete in US markets. He was angered when Queen Liliuokalani, who succeeded her brother Kalakaua in 1891, tried to restore royal power.

In 1893 Dole joined a group of businessmen who, aided by the presence of US Marines, overthrew the monarchy. The next year he became president of the new Republic of Hawai‘i.

Sanford Dole pressed for annexation, but it was delayed until 1898, when Hawaii became a strategic naval base during the Spanish-American War. In 1900 Dole was appointed governor of the new territory.

In 1903 he became presiding judge of the Federal District Court, a position he held until his retirement in 1915. Sanford Dole died in Honolulu on June 9, 1926. (Britannica)

Charles Fletcher Dole (1845–1927) – first cousin to Sanford Dole – was a Unitarian minister; after teaching Greek for a time at the University of Vermont, he was called by the Jamaica Plain church. Reverend Charles Dole served for more than forty years as pastor of the First Church of Jamaica Plain, MA.

He was prolific writer of books and pamphlets in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston, MA, and Chairman of the Association to Abolish War. Charles Dole authored a substantial number of books on politics, history and theology.

Charles Dole often expressed the hope that his son, James, would enter the ministry. (Jamaica Plain Historical Society) However, James (they called him Jim) concentrated on agriculture and horticulture.

James Dole’s love of farming had grown out of his boyhood experiences at the family’s summer home in Southwest Harbor, Maine. His summer chore was to take care of the family’s vegetable garden. What would have been a burden to most boys was a delight to Jim, and he gradually concluded that his “calling” was not the ministry but “the land.”

James Dole made his way to Hawai‘i with his total savings of about $1,500, intent upon making his fortune. Having just turned 22, this 5’ 11½”, 120 pound Harvard graduate landed in Honolulu on November 16, 1899.

At first he lived with his cousin Sanford. “Within two weeks I found the town quarantined for six months by an outbreak of bubonic plague. During the winter I saw the fire department, with the timely aid of a stiff wind, burn down all of Chinatown (the intention being to disinfect in this thorough manner only one or two blocks).”

The Hawaiian economy was dependent on a single product, sugar, and its fortunes bobbed up and down with the fortunes of sugar. James Dole wrote: “I first came to Hawaii … with some notion of growing coffee – the new Territorial Government was offering homestead lands to people willing to farm them – and I had heard that fortunes were being made in Hawaiian coffee.”

“I began homesteading a [64 acre] farm in the rural district of the island of Oahu, at a place called Wahiawa, about 25 miles from Honolulu.”

“On August 1, 1900 [I] took up residence thereon as a farmer – unquestionably of the dirt variety. After some experimentation, I concluded that it was better adapted to pineapples than to [coffee,] peas, pigs or potatoes, and accordingly concentrated on that fruit.”

Previous growers had tried to ship pineapples as a fresh fruit, but pineapple does not travel well and they did not prosper. James Dole’s intention was to distribute pineapple in cans – also an endeavor at which others had failed.

Undeterred, he planted about 75,000 pineapple slips on twelve of his acres, and simultaneously, with no knowledge of canning, he started a small cannery. “The people of Honolulu scoffed when, in December 1901, 24-year-old James Dole founded the Hawaiian Pineapple Company [Hapco]…”

The Honolulu Advertiser labeled the company “a foolhardy venture which had been tried unsuccessfully before and was sure to fail again.” In another editorial, the paper said, “If pineapple paid, the vacant lands near the town would be covered with them….Export on any great or profitable scale is out of the question.”

in 1910, Sanford Dole wrote to James Dole: “The more I think about it the less I like the proposition of using the Dole name for your enterprise. It is a name which has long been associated in these islands with religious, educational, and philanthropic enterprises…”

“I think it would be regrettable to give [the name Dole] an association of such a commercial character that would adhere to it if made a trade-mark or part of the business name of a corporation.”

James Dole adhered to his cousin’s wishes while he controlled Hapco, but the leaders of the reorganized company soon began exploiting the Dole name in labels and advertising. And after James’s death, Hapco was renamed the Dole Food Company.

Thirty years later – in 1930 – the company (popularly known as “Hapco”) had well over a billion plants in the ground and was packing 104,515,025 cans of pineapple a year for world-wide distribution. (Lots here is from F Washington Jarvis.)