by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

by Peter T Young 2 Comments

After Kuakini’s death in 1844, the Palace passed to his adopted son, William Pitt Leleiohoku. Leleiohoku died a few months later, leaving Hulihe‘e to his wife, Princess Ruth Luka Ke‘elikōlani. It became a favorite retreat for members of the Hawaiian royal family.

by Peter T Young 2 Comments

Transit of Venus

Interest in the heavens goes back far into the ancient fabric of Polynesian culture. Many of the early Polynesian gods derived from or dwelt in the heavens, and many of the legendary exploits took place among the heavenly bodies.

Early Polynesians, who trusted their navigational instincts and skills to the nighttime stars above, currents, winds and waves, sailed thousands of miles over open ocean across the Pacific to Hawai‘i.

They had names for their star guides: Ka Maka – the point of the fishhook in the constellation Scorpius; Makali‘i – the Little Eyes within the Pleiades; Hoku‘ula – The Red Star in the constellation Taurus; and Hokupa‘a – the North Star (fixed star,) as well as others.

After the Polynesians came, in 1778, the Europeans, under the command of Captain James Cook, arrived. He brought with him spyglasses, clocks, sextants, charts, foreign ideas and techniques – new tools of navigation.

A new awareness of the skies was reborn under the scientific patronage of King David Kalākaua, (Kalākaua reigned over the Kingdom of Hawai‘i from 1874 to 1891.)

Kalākaua had a great interest in science and he saw it as a way to foster Hawai‘i’s prestige, internationally.

The opportunity to demonstrate this interest and support for astronomy was made available with the astronomical phenomenon called the “Transit of Venus,” which was visible in Hawai‘i in 1874.

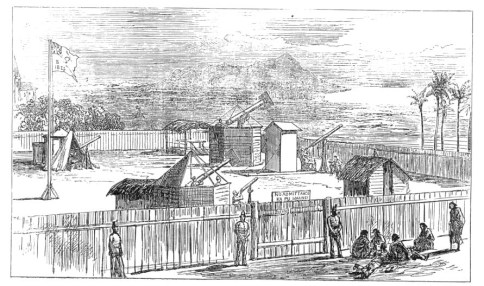

The King allowed the British Royal Society’s expedition a suitable piece of open land for their viewing area; it was not far from Honolulu’s waterfront in a district called Apua (mauka of today’s Waterfront Plaza.)

They built a wooden fence enclosure and soon a well-equipped nineteenth-century astronomical observatory took shape, including a transit instrument, a photoheliograph, a number of telescopes and several temporary structures including wooden observatories.

Subsequently, auxiliary stations – though not so elaborate as the main station in Honolulu – were established in two other island locations: one at Kailua-Kona and the other at Waimea, Kauai.

In addition, Hawai‘i was not the only site to observe the transit; under the British program, observations were also made in Egypt, Island of Rodriquez, Kerguelen Island and New Zealand. (Other countries also conducted Transit observations.)

On Dec. 8, 1874, the transit was observed by the British scientists; however, the observation at Kailua-Kona was marred by clouds. But the Honolulu and Waimea sites were considered perfect throughout the event, which lasted a little over half a day.

After the Transit of Venus observations, Kalākaua showed continued interest in astronomy, and in a letter to Captain RS Floyd on November 22, 1880, he expressed a desire to see an observatory established in Hawai‘i. He later visited Lick Observatory in San Jose.

It was not long after this that a telescope was purchased from England in 1883 and set up at Punahou School.

In 1884, the five-inch refractor was installed in a dome constructed above Pauahi Hall on the school’s campus (the first permanent telescope in Hawai‘i.)

In 1956, this telescope was installed in Punahou’s newly completed MacNeil Observatory and Science Center. (Unfortunately, it is not known where that telescope is today.

Why was the Transit of Venus important?

Although Copernicus had, by the 16th century, put the known planets in their correct order, their absolute distances remained unknown. Astronomers still needed a celestial yardstick of “Astronomical Units” with which to measure distances among the planets and to link the planets to the stars beyond.

The mission of the British expedition was to observe a rare transit of Venus across the Sun for the purpose of better determining the value of the Astronomical Unit – that is, the Earth-to-Sun distance – and from it, the absolute scale of the solar system.

The orbits of Mercury and Venus lie inside Earth’s orbit, so they are the only planets which can pass between Earth and Sun to produce a transit (a transit is the passage of a planet across the Sun’s bright disk.) Transits are very rare astronomical events; in the case of Venus, there are on average two transits every one and a quarter centuries.

Ironically, on December 8, 1874 the big day, the king was absent, being in Washington to promote Hawaiian interests in a new trade agreement with the United States.

When American astronomer Simon Newcomb combined the 18th century data with those from the 1874/1882 Venus transits, he derived an Earth-sun distance of 149.59 +/- 0.31 million kilometers (about 93-million miles), very close to the results found with modern space technology in the 20th century.

by Peter T Young 12 Comments

During the 1920s, the Waikīkī landscape was transformed when the construction of the Ala Wai Drainage Canal, begun in 1921 and completed in 1928, resulted in 625-acres of wetland being drained and filled. With the San Souci, Moana and Royal Hawaiian in place, more hotel construction followed.

Except for Waikīkī, Hawaiʻi was largely undeveloped for tourism, other than small places like the Big Island’s Volcano House, which started to welcome guests in 1866.

In order for the Islands to attract even greater numbers of visitors, it was obvious that the neighbor islands would have to provide accommodations comparable to those on Oʻahu. (Allen)

With several smaller business-oriented hotels downtown Honolulu and spotted across the neighbor islands, on November 1, 1928, the Kona Inn in Kailua-Kona, the first neighbor island visitor-oriented resort hotel, opened with great fanfare. (Hibbard, Schmitt)

The Inter-Island Steam Navigation Co originally intended to build the Kona Inn on the site of Huliheʻe Palace. The idea was met with considerable opposition and the Territory bought the Palace and the company erected its new hotel on a 4-acre parcel adjoining the former Royal Residence. (Hibbard)

A reported Star-Bulletin editorial noted on February 7, 1928, “The land of the first Kamehameha; the land which cradled the old Federation of the Hawaiian Islands; the storied land where an English ship’s captain was worshipped before natives found him human and slew him there, is to be opened at last to the comfort-loving tourists of the world. Soon after the completion of the hotel, the territory will have cause to be grateful to the foresight and enterprise of Inter-Island.”

When it opened, a description noted that “every room is equipped with connecting bath and toilet or connecting shower and toilet with hot and cold water.” (Shared facilities disappeared from most hotels soon after World War II.) (Schmitt)

Like many of the other early visitor-oriented accommodations, it was owned by a transportation company, Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company, under the guidance of Stanley Kennedy. In part, hotels served to increase their passenger load revenues.

He informed the newspapers, “We have the Volcano House in the Kilauea locality, and our new hotel in the Kona district on the end of the island makes an ideal (automobile) stopping place, to say nothing of the historical interest.”

This institutionalized tourism in Kona. It was an example of a ‘pioneer hotel;’ it was built at high standards and became an attraction in its own right and became “the spot in all Hawaiʻi where you can utterly, completely relax in surroundings of modern comfort.” (Thrum, Butler)

But the decision to build a visitor resort there was not without its cynics; numerous skeptics suggested it as “Kennedy’s Folly.”

They were wrong; it was a success.

Kona, and the Kona Inn, offered the opportunity for visitors to experience the “Kona Way of Life” – ambiance at almost a spiritual level. It became known as “a place to get a quiet rest amid soothing tropic surroundings but if you feel a bit lively one can find plenty to do.” (DeVisNorton, Butler)

Within two years, designer CW Dickey prepared plans to double its size. With that, the Advertiser reportedly noted, “It is expected that Kona Inn will have a capacity to accommodate even the heaviest weeks of travel. Since its opening, Kona Inn has proved to be a valuable asset to Inter-Island and the addition is a result of continuous patronage of tourists and local people.” (Hibbard)

The early success of the Kona Inn was short lived; like other businesses across the Islands and the continent, the Great Depression and then World War II decimated the operations at the Kona Inn. It was two-decades before any major hotels were built; however, after the war, recovery accelerated at an unimaginable and spectacular pace. (Hibbard)

In the late-1940s, Inter-Island Steam Navigation Co became the target of a federal anti-trust suit. The government won its case and broke the company into four companies: Inter-Island Steam, Overseas Terminals, Hawaiian Airlines and Inter-Island Resorts. (GardenIsland)

In the early-1950s, Walter D Child Sr became a director of Inter-Island Resorts, Ltd and later acquired the controlling interest in the company.

Child first came to the Islands in the early-1920s and worked with the Hawaiʻi Sugar Planters Association. Following a decade at HSPA, he left sugar and entered the visitor industry, first acquiring and operating the Blaisdell Hotel in downtown Honolulu in 1938; then, he formed a Hui and purchased the Naniloa in Hilo.

The fortunes of the company rose along with the growth in the visitor industry, and Inter-Island Resorts began to grow into a chain, starting with the Naniloa, the Kona Inn and the Kaua‘i Inn (at Kalapaki Beach.) In those early days of Hawai‘i tourism, Inter-Island Resorts became a pioneer in selling accommodations on the neighbor islands. (hawaii-edu)

When Walter Sr. suffered a debilitating stroke in 1955, Dudley Child succeeded his father as president, at age 26. Dudley was no stranger to the visitor industry; at age seven, he was running switch boards and elevators and later studied hotel management at Cornell University.

Dudley’s first big move came on July 1, 1960 with the opening of the Kauai Surf on beachfront property on Kalapakī Beach. Child at the time called the Surf a “whole new philosophy in Neighbor Island hotels.” This led to the Islands-wide “Surf Resorts” joining the Kona Inn under the Inter-Island banner. (The company later opened the Kona Surf (Keauhou) in 1960 and the Maui Surf (Kāʻanapali Beach in 1971.) In 1971, the company formed the “Islander Inns,” in a 3-way partnership of Inter-Island Resorts, Continental Airlines and Finance Factors.)

In the mid-1970s, growing competition from the big hotel chains affected their business; direct flights to Hilo from the continent stopped, killed the occupancy rates at the Naniloa; later, a United Airlines strike sent Islands-wide occupancy levels plummeting; an economic downturn added to the woes. The high-leveraged Inter-Island Resorts had to sell.

In 1976, the Kona Inn, forerunner to the Inter-Island chain, was sold and overnight guest accommodations were stopped; it was converted into a shopping center in 1980. Chris Hemmeter bought the Maui and Kauai Surf resorts; ultimately, piece by piece, all properties were sold. (All photos in this album are from Hawaiʻi State Archives and are all from the 1930s.)

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

Captain George Vancouver gave a few cattle to Kamehameha I in 1793; Vancouver strongly encouraged Kamehameha to place a kapu on them to allow the herd to grow.

In the decades that followed, cattle flourished and turned into a dangerous nuisance. By 1846, 25,000 wild cattle roamed at will and an additional 10,000 semi‐domesticated cattle lived alongside humans.

John Adams Kuakini was an important adviser to Kamehameha I in the early stages of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.

When the Kingdom’s central government moved to Lāhaina in 1820, Kuakini’s influence expanded on Hawaiʻi Island, with his appointment as the Royal Governor of Hawaiʻi Island, serving from 1820 until his death in 1844.

During his tenure, Kuakini built many of the historical sites that dominate Kailua today. The Great Wall of Kuakini, probably a major enhancement of an earlier wall, was one of these.

The Great Wall of Kuakini extends in a north-south direction for approximately 6 miles from Kailua to near Keauhou, and is generally 4 to 6-feet high and 4-feet wide.

Built between 1830 and 1840, the Great Wall of Kuakini separated the coastal lands from Kailua to Keauhou from the inland pasture lands.

The mortar-less lava-rock wall has had varying opinions regarding the purpose of its construction.

Speculation has ranged from military/defense to the confinement of grazing animals; however, most seem to agree it served as a cattle wall, keeping the troublesome cattle from wandering through the fields and houses of Kailua.

It is likely that the function of the wall changed over time, as the economic importance of cattle grew and the kinds and density of land use and settlement changed.

Kuakini was responsible for other changes and buildings in the Kona District during this era.

He gave land to Asa Thurston to build Moku‘aikaua Church.

He built Huliheʻe Palace in the American style out of native lava, coral lime mortar, koa and ‘ōhi‘a timbers. Completed in 1838, he used the palace to entertain visiting Americans and Europeans with great feasts.

Hulihe‘e Palace is now a museum run the Daughters of Hawaiʻi, including some of his artifacts.

He made official visits to all ships that arrived on the island, offering them tours of sites, such as the Kīlauea volcano.

He was born about 1789 with the name Kaluaikonahale. With the introduction of Christianity, Hawaiians were encouraged to take British or American names.

He chose the name John Adams after John Quincy Adams, the US president in office at the time. He adopted the name, as well as other customs of the US and Europe.

Kuakini was the youngest of four important siblings: sisters Queen Kaʻahumanu, Kamehameha’s favorite wife who later became the powerful Kuhina nui, Kalākua Kaheiheimālie and Namahana-o-Piʻia (also queens of Kamehameha) and brother George Cox Kahekili Keʻeaumoku.

He married Analeʻa (Ane or Annie) Keohokālole; they had no children. (She later married Caesar Kapaʻakea. That union produced several children (including the future King Kalākaua and Queen Liliʻuokalani.)

A highway is named “Kuakini Highway,” which runs from the Hawaii Belt Road through the town of Kailua-Kona, to the Old Kona Airport Recreation Area.

He is also the namesake of Kuakini Street in Honolulu, which is in turn the namesake of the Kuakini Medical Center on it.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

Follow Peter T Young on LinkedIn

Follow Peter T Young on Blogger