Clarence Hyde Cooke was born April 17, 1876 in Honolulu, Hawaii, the second son of Charles Montague Cooke and Anna Rice Cooke (and grandson of missionaries Amos Starr Cooke and William Harrison Rice.) He graduated from Punahou (1894,) and attended, but did not graduate from Yale.

He married Lily Love, daughter of Robert Love on August 11, 1898; they had eight children: Dorothea, Martha, Anna, Clarence Jr, Harrison, Alice, Robert and John.

Cooke began his business career in Honolulu with Hawaiian Safe Deposit & Trust Co, in 1897. The next year he was at Bank of Hawaiʻi and about 10-years later (1909,) he succeeded his father as president of the bank and became Chairman in 1937.

In 1932, the Cooke’s built a home in Nuʻuanu (unfortunately, Lily died the next year.) The home was designed by Hardie Phillip, one of the associates of the New York architectural firm of Mayers, Murray and Phillip, the successor firm of Bertram Goodhue and Associates (who also designed the C Brewer Building, Governor Carter’s residence and others.)

The home has the distinctive double-pitched ‘Dickey Roof’ (following the signature element of architect CW Dickey.) The 24-room Cooke mansion (including 10-bedrooms, 7-full bathrooms and two half-baths) is noted for its sprawling spaciousness, numerous lanai, Hawaiian hipped roof and lush grounds.

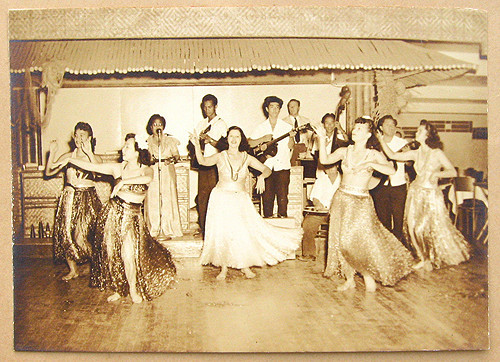

Well-planned, well-crafted and paying high attention to detail, the house was built for, and was known for, lavish, opulent entertainment. As such, it epitomizes the finest traditions in upper class residential design in Hawaii for its period. (HHF)

The two-story white-washed brick and frame residence features an asymmetrical plan which lends the building a sense of sprawling informality. The house is laid out with two wings running perpendicularly in opposite directions off a formal entry hall. A number of lanai extend out from the principal rooms on both the ground and second floors.

A vine covered porte-cochere, shaded by a banyan tree, extends diagonally out from the intersection of the makai (left) wing and the entry area. It has segmental arched openings, and is paved with Chinese granite blocks. A tiled fountain is in the corner of the porte-cochere. (NPS)

Cooke lived there until his death on August 2, 1944. He bequeathed the estate to the Academy of Arts (architect Hardie Phillip also designed the Honolulu Academy of Arts building on Beretania.)

The Academy later (1945) sold the home to Alfred Lester and Elizabeth ((daughter of Lincoln L McCandless) Marks. (Since then, the property has been generally referred to as the “Marks Estate.”)

At about this time, Johnny Wilson, the builder of the original carriage-road over the Pali, was re-elected Mayor (1948.) One of his first actions was to seek approval from the Territorial Legislature for an increase in the gasoline tax to pay for a tunnel in Kalihi Valley.

Wilson argued the Kalihi alternative would serve the entire windward side, while the Pali would merely be a private access road for Kailua residents.

The Territorial legislature turned down Wilson’s 1949 gas tax proposal for the Kalihi tunnel. That same year, Governor Ingram M Stainback looked to build the Pali Highway alignment, instead. (ASCE) (This alignment would cut through the Marks Estate.)

Marks went to court to block the proposed highway. After lengthy legal battles, in 1956, the government bought 7-acres of the 17-acre estate, and also bought the home and other improvements.

(On May 11, 1957, the Honolulu-bound tunnels on Pali Highway were opened; the Pali Tunnels were fully-functional in 1959. The Kalihi ‘Wilson Tunnels’ were also later built and fully operational by November 1960.)

Although the State condemned and bought the property and home, they allowed Marks to continue to live there (the Marks paid $1,500-per month for the first three years, then $500-per month until 1976, then the State took over the property.)

After that, the now-defunct Hawaiʻi Institute for Management and Analysis in Government, part of the Department of Budget and Finance, acquired the property for a research, training and conference center. (The Institute was later absorbed into DBEDT.) (Danninger)

The State government then used the estate for office space, conferences and special events, and it was put on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.

After trying to sell it for years, the State finally auctioned off the property in 2002. Reportedly, it had been appraised for $4.5-million, but labor union Unity House Inc bought it for $2.5-million.

Real property tax records note a subsequent (2006) conveyance of the property for $4.41-million. Later listings note the property has since been on and off the market.