by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

Born in the early-1800s, Boaz Mahune was a member of the lesser strata of Hawaiian nobility, subordinate to the high chiefs or aliʻi. He was a cousin of Paul Kanoa, who served as Governor of Kauai from 1846 to 1877.

He adopted the name “Boaz” after a figure in The Book of Ruth in the Bible, after his conversion to Christianity (it was sometimes spelled Boas.)

Boaz Mahune was a member of the first class at Lahainaluna Seminary, graduating in 1835 after four years there. His classmates included historian David Malo and royal diplomat Timothy Haʻalilio.

He was considered one of the school’s most brilliant scholars and was one of the ten chosen to remain as monitors, teachers in the children’s school and assistants in translating.

Mahune (with others from Lahainaluna) drafted the 1839 Hawaiian Bill of Rights, also known as the 1839 Constitution of Hawaiʻi. This document was an attempt by King Kamehameha III and his chiefs to guarantee that the Hawaiian people would not lose their tenured land, and provided the groundwork for a free enterprise system.

It laid down the inalienable rights of the people, the principles of equality of between the makaʻāinana (commoner) and the aliʻi (chiefs) and the role of the government and law in the kingdom.

Many refer to that document as Hawaiʻi’s Magna Charta (describing certain liberties, putting actions within a rule of law and served as the foundation for future laws.) It served as a preamble to the subsequent Hawaiʻi Constitution (1840.)

It was a great and significant concession voluntarily granted by the king to his people. It defined and secured the rights of the people, but it did not furnish a plan or framework of the government. (Kuykendall)

After several iterations of the document back and forth with the Council of Chiefs, it was approved and signed by Kamehameha III on June 7, 1839 – it was a significant departure from ancient ways.

As you can see in the following, the writing was influenced by Christian fundamentals, as well as rights noted in the US Declaration of Independence.

Ke Kumukānāwai No Ko Hawaiʻi Nei Pae ʻĀina 1839 (Declaration of Rights (1839)

“God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on the earth, in unity and blessedness. God has also bestowed certain rights alike on all men and all chiefs, and all people of all lands.”

“These are some of the rights which He has given alike to every man and every chief of correct deportment; life, limb, liberty, freedom from oppression; the earnings of his hands and the productions of his mind.”

“God has also established governments and rule for the purpose of peace; but in making laws for the nation it is by no means proper to enact laws for the protection of the rulers only, without also providing protection for their subjects; neither is it proper to enact laws to enrich the chiefs only, without regard to enriching their subjects also, and hereafter there shall by no means be any laws enacted which are at variance with what is above expressed, neither shall any tax be assessed, nor any service or labor required of any man, in a manner which is at variance with the above sentiments.”

“These sentiments are hereby proclaimed for the purpose of protecting alike, both the people and the chiefs of all these islands, while they maintain a correct deportment; that no chief may be able to oppress any subject, but that chiefs and people may enjoy the same protection, under one and the same law.”

“Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people, together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws. Whatever chief shall act perseveringly in violation of this Constitution, shall no longer remain a chief of the Hawaiian Islands, and the same shall be true of the Governors, officers and all land agents.”

The Declaration of Rights of 1839 recognized three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands; 1st, the Government; 2nd, the Chiefs; and 3rd, the native Tenants. It declared protection of these rights to both the Chiefly and native Tenant classes.

Mahune is more specifically credited with nearly all the laws on taxation in the introduction to the English translation of the laws of 1840, not published until 1842.

Later he was Kamehameha III’s secretary and advisor. When the king attempted to start a sugar cane plantation at Wailuku on Maui, Mahune was the manager. The project was not a success.

Mahune returned to Lāhainā, where he acted as a judge for a time. About 1846 he went back to his home in Honolulu to work for the government. Mahune died in March 1847.

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of American Protestant missionaries from the northeast US set sail on the Thaddeus for the Sandwich Islands (now known as Hawai‘i.) There were seven American couples sent by the ABCFM in this first company.

These included two Ordained Preachers, Hiram Bingham and his wife Sybil and Asa Thurston and his wife Lucy; two Teachers, Mr. Samuel Whitney and his wife Mercy and Samuel Ruggles and his wife Mary; a Doctor, Thomas Holman and his wife Lucia; a Printer, Elisha Loomis and his wife Maria; and a Farmer, Daniel Chamberlain, his wife and five children.

By the time the Pioneer Company arrived, Kamehameha I had died and the centuries-old kapu system had been abolished; through the actions of King Kamehameha II (Liholiho,) with encouragement by former Queens Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani (Liholiho’s mother,) the Hawaiian people had already dismantled their heiau and had rejected their religious beliefs.

One of the first things the missionaries did was begin to learn the Hawaiian language and create an alphabet for a written format of the language. Their emphasis was on teaching and preaching.

The first mission station was at Kailua-Kona, where they first landed in the Islands, then the residence of the King (Liholiho, Kamehameha II;) Asa and Lucy Thurston manned the mission, there.

Liholiho was Asa Thurston’s first pupil. His orders were that “none should be taught to read except those of high rank, those to whom he gave special permission, and the wives and children of white men.”

James Kahuhu and John ʻlʻi were two of his favorite courtiers, whom he placed under Mr. Thurston’s instruction in order that he might judge whether the new learning was going to be of any value. (Alexander, The Friend, December 1902)

In 1820, Missionary Lucy Thurston noted in her Journal, “The king (Liholiho, Kamehameha II) brought two young men to Mr. Thurston, and said: ‘Teach these, my favorites, (John Papa) Ii and (James) Kahuhu. It will be the same as teaching me. Through them I shall find out what learning is.’”

“To do his part to distinguish and make them respectable scholars, he dressed them in a civilized manner. They daily came forth from the king, entered the presence of their teacher, clad in white, while his majesty and court continued to sit in their girdles.”

“Although thus distinguished from their fellows, in all the beauty and strength of ripening manhood, with what humility they drank in instruction from the lips of their teacher, even as the dry earth drinks in water!”

“After an absence of some months, the king returned, and called at our dwelling to hear the two young men, his favorites, read. He was delighted with their improvement, and shook Mr. Thurston most cordially by the hand – pressed it between both his own – then kissed it.” (Lucy Thurston)

Kahuhu was among the earliest of those associated with the chiefs to learn both spoken and written words. Kahuhu then became a teacher to the chiefs.

In April or May 1821, the King and the chiefs gathered in Honolulu and selected teachers to assist Mr Bingham. James Kahuhu, John ʻĪʻi, Haʻalilio, Prince Kauikeaouli were among those who learned English. (Kamakau)

On October 7, 1829, it seems that Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) set up a legislative body and council of state when he prepared a definite and authoritative declaration to foreigners and each of them signed it. (Frear – HHS) Kahuhu was one of the participants.

King Kamehameha III issued a Proclamation “respecting the treatment of Foreigners within his Territories.” It was prepared in the name of the King and the Chiefs in Council: Kauikeaouli, the King; Gov. Boki; Kaʻahumanu; Gov. Adams Kuakini; Manuia; Kekūanāoʻa; Hinau; ʻAikanaka; Paki; Kīnaʻu; John ʻIʻi and James Kahuhu.

In part, he states, “The Laws of my Country prohibit murder, theft, adultery, fornication, retailing ardent spirits at houses for selling spirits, amusements on the Sabbath Day, gambling and betting on the Sabbath Day, and at all times. If any man shall transgress any of these Laws, he is liable to the penalty, – the same for every Foreigner and for the People of these Islands: whoever shall violate these Laws shall be punished.”

It continues with, “This is our communication to you all, ye parents from the Countries whence originate the winds; have compassion on a Nation of little Children, very small and young, who are yet in mental darkness; and help us to do right and follow with us, that which will be for the best good of this our Country.”

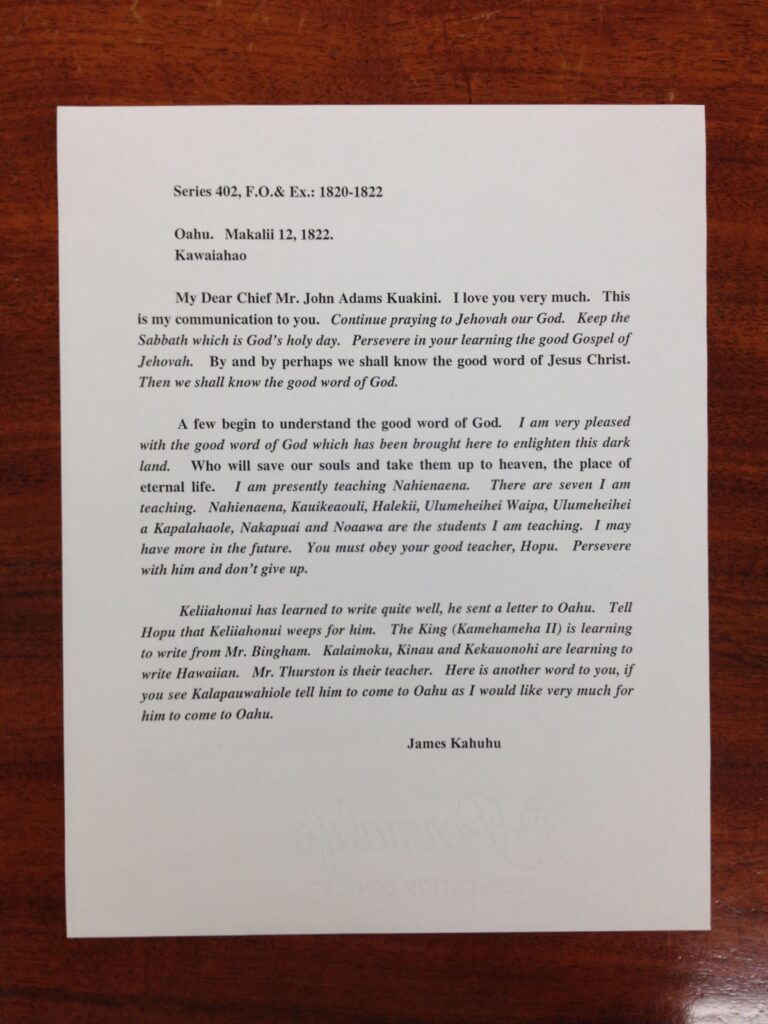

The Hawaiʻi State Archives is the repository of significant historic documents for Hawaiʻi; reportedly, the oldest Hawaiian language document in its possession is a letter written by James Kahuhu.

Writing to Chief John Adams Kuakini, Kahuhu’s letter was partially in English and partially Hawaiian (at that time, Kuakini was learning both English and written Hawaiian.)

Below is a transcription of Kahuhu’s letter. (HSA)

Oahu. Makaliʻi 12, 1822.

Kawaiahaʻo.

My Dear Chief Mr. John Adams Kuakini. I love you very much. This is my communication to you. Continue praying to Jehovah our God. Keep the Sabbath which is God’s holy day. Persevere in your learning the good Gospel of Jehovah. By and by perhaps we shall know the good word of Jesus Christ. Then we shall know the good word of God.

A few begin to understand the good word of God. I am very pleased with the good word of God which has been brought here to enlighten this dark land. Who will save our souls and take them up to heaven, the place of eternal life. I am presently teaching Nahiʻenaʻena. I am teaching seven of them. Nahienaena, Kauikeaouli, Halekiʻi, Ulumāheihei Waipa, Ulumāheihei a Kapalahaole, Nakapuai and Noaʻawa are the students I am teaching. I may have more in the future. You must obey your good teacher, Hopu. Persevere with him and don’t give up.

Keliʻiahonui has learned to write quite well, he sent a letter to Oahu. Tell Hopu that Keliʻiahonui misses him. The King is learning to write from Mr. Bingham. Kalanimōku, Kīnaʻu and Kekauōnohi are learning to write Hawaiian. Mr. Thurston is their teacher. Here is another word to you, if you see Kalapauwahiole tell him to come to Oahu as I would like very much for him to come to Oahu.

James Kahuhu

(Makaliʻi was the name of a month: December on Hawai‘i, April on Moloka’i, October on Oʻahu. (Malo))

The image shows the first page of the Kahuhu letter to Kuakini (HSA.)

by Peter T Young 1 Comment

Robert Crichton Wyllie was born October 13, 1798 in an area called Hazelbank in Dunlop parish of East Ayrshire, Scotland. His father was Alexander Wyllie and his mother was Janet Crichton.

He earned a medical diploma by the time he was 20. In 1844, he arrived in Hawaiʻi and stayed in the Hawaiian Islands for the rest of his life.

Wyllie first worked as acting British Consul. During this time he compiled in-depth reports on the conditions in the islands. Attracted by Wyllie’s devotion to the affairs of Hawaiʻi, on March 26, 1845, King Kamehameha III appointed him the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Kamehameha IV reappointed all the ministers who were in office when Kamehameha III died, including Robert C. Wyllie as Minister of Foreign Relations. Wyllie served as Minister of Foreign Relations from 1845 until his death in 1865, serving under Kamehameha III, Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V.

Within five years after taking the helm of the office he had negotiated treaties with Denmark, England, France and the United States whereby Hawaiʻi’s status as an independent state was agreed.

Wyllie eventually gave up his allegiance to Queen Victoria and became a naturalized Hawaiian subject.

In 1847, Wyllie started collecting documents to form the Archives of Hawaii. He requested the commander of the fort in Honolulu and all the chiefs to send in any papers they might have. Two of the oldest documents included the 1790 letter of Captain Simon Metcalf and a letter by Captain George Vancouver dated 1792.

The foundation of the Archives of Hawaiʻi today are based almost entirely upon the vast, voluminous collections of letters and documents prepared and stored away by Wyllie.

Wyllie built a house in Nuʻuanu Valley he called Rosebank. He entertained foreign visitors at the house, and the area today still has several consular buildings.

In his role in foreign affairs, Wyllie was seen as a counter to the American influence. Wyllie wrote in the early part of 1857, “There are two grand principles that we aspire to; the first is that all nations should agree to respect our independence and consider the Archipelago strictly neutral in all wars that may arise – and the second is, to have one identical Treaty with all nations.” (Kuykendall)

Of these two principles, the second was auxiliary to the first. Wyllie’s great ambition was to set up some permanent barrier against any possible threat to Hawaii’s national independence. He had a clear idea as to the direction from which danger was most likely to come. (Kuykendall)

In the latter part of 1857 he wrote, “If we be left to struggle for political life, under our own weakness and inability to keep up an adequate military and naval force, in the natural course of things, the Islands must sooner or later be engulfed into the Great American Union, in which case, in time of war, the United States would be able to sweep the whole Northern Pacific.” (Kuykendall)

Wyllie, above all other men in Hawaiʻi, succeeded in compelling the powers to maintain an attitude of “hands off”, leaving the kingdom in the list of independent nations. (Taylor)

In March 1853, he bought a plantation on Hanalei Bay on the north shore of the island of Kauaʻi. In 1860, he hosted his friends King Kamehameha IV, Queen Emma and their two-year-old son, Prince Albert, at his estate for several weeks. In honor of the child, Wyllie named the plantation the “Barony de Princeville”, the City of the Prince (Princeville.)

Originally the land was planted with coffee; eventually it was planted with sugarcane. Princeville became a ranch in 1895, when missionary son Albert S Wilcox bought the plantation.

A bachelor all his life, Wyllie died October 19, 1865 at the age of 67; Kamehameha V and the chiefs ordered the casket containing his remains be buried at Mauna ʻAla, the Royal Mausoleum, adjacent to those of the sovereigns and chiefs of Hawaiʻi.

Members of Queen Emma’s family are also interred in the crypt with Mr. Wyllie: Queen Emma’s mother, Kekelaokalani; her hānai parents, Grace Kamaikui and Dr. Thomas Charles Byde Rooke; her uncles, Bennett Namakeha and Keoni Ana John Young II; her aunt, Jane Lahilahi; and her two cousins, Prince Albert Edward Kunuiakea and Peter Kekuaokalani.

by Peter T Young 1 Comment

While on a trip to the continent, Queen Kamāmalu (age 22) died on July 8, 1824; King Kamehameha II (Liholiho, age 27) died six days later on July 14, 1824. (Prior to his death he asked to return and be buried in Hawai‘i.)

Upon their arrival in Hawai‘i, in consultation between the Kuhina Nui (former Queen Kaʻahumanu) and other high chiefs, and telling them about Westminster Abbey and the underground burial crypts they had seen there, it was decided to build a mausoleum building.

In 1825, Pohukaina (translated as “Pohu-ka-ʻāina” (the land is quiet and calm)) was constructed on what is now the grounds of ʻIolani Palace to house the remains of Kamehameha II (Liholiho) and Queen Kamāmalu.

The mausoleum was a small 18 x 24-foot Western style structure made of white-washed coral blocks with a thatched roof; it had no windows. Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu were buried on August 23, 1825.

About this same time, April 25, 1825, Richard Charlton arrived in the Islands to serve as the first British consul. He had been in London during Kamehameha II’s visit in 1824.

Nearly 10-years later, in 1832, Kaʻahumanu died; her death took place at ten minutes past 3 o’clock on the morning of June 5, “after an illness of about 3 weeks in which she exhibited her unabated attachment to the Christian teachers and reliance on Christ, her Saviour.” (Hiram Bingham)

The Kaʻahumanu services were performed by Bingham. After the sermon in Hawaiian, he addressed the foreigners present and the mission family. After the close of the services, the procession was again formed and walked to Pohukaina, where the body was deposited, with the remains of others in the Royal family. (The Friend, June 1932)

The above helps set the stage for subsequent events that happened there.

Nearly 10-years later, in 1840, Charlton made a claim for several parcels of land in Honolulu. At the time the lease was made, Kaʻahumanu was Kuhina Nui and only she and the king could make such grants. The land was Kaʻahumanu’s in the first place, and Kalanimoku certainly could not give it away. (Hawaiʻi State Archives) The dispute dragged on for years.

This, and other grievances purported by Charlton and the British community in Hawai‘i, led to the landing of George Paulet on February 11, 1843.

He noted in a letter to the King, “I have the honor to notify you that Her Britannic Majesty’s ship Carysfort, under my command, will be prepared to make an immediate attack upon this town at 4 pm tomorrow (Saturday) in the event of the demands now forwarded by me to the King of these islands not being complied with by this time.”

On February 25, the King acceded to his demands. Under the terms of the new government the King and his advisers continued to administer the affairs of the Hawaiian population.

It soon became clear that Paulet had no intention of limiting his rule to the affairs of foreigners. New taxes were imposed, liquor laws were relaxed. Paulet refused to restore the old laws. After raising multiple objections to the actions by Paulet, Judd resigned from the commission on May 11. (Daws)

Fearing that Paulet would seize some of the archives and other national records, Gerrit P Judd took them from the government house, and secretly placed them in the royal tomb at Pohukaina. He used the mausoleum as his office.

By candlelight, using the coffin of Kaʻahumanu for a table, Judd prepared appeals to London and Washington to free Hawaiʻi from the illegal rule of Paulet.

Dispatches were sent off in canoes from distant points of the island; and once, when the king’s signature was required, he came down in a schooner and landed at Waikīkī, read and signed the prepared documents, and was on his way back across the channel, while Paulet was dining and having a pleasant time with his friends. (Laura F Judd)

For about five months the islands were under the rule of the British commission set up by Lord George Paulet. Queen Victoria, on learning these activities, immediately sent an envoy to the islands to restore sovereignty to its rightful rulers. Finally, Admiral Richard Thomas arrived in the Islands on July 26, 1843 to restore the kingdom to Kamehameha III.

Then, on July 31, 1843, Thomas declared the end of the Provisional Cession and recognizes Kamehameha III as King of the Hawaiian Islands and the Islands to be independent and sovereign; the Hawaiian flag was raised. This event is referred to as Ka La Hoʻihoʻi Ea, Sovereignty Restoration Day, and it is celebrated each year in the approximate site of the 1843 ceremonies, Thomas Square.

Nearly 20-years later, Pohukaina was the final resting place for the Hawaiʻi’s Kings and Queens, and important chiefs of the kingdom. Reportedly, in 1858, Kamehameha IV brought over the ancestral remains of other Aliʻi – coffins and even earlier grave material – out of their original burial caves, and they are buried in Pohukaina.

In 1865, the remains of 21-Ali‘i were removed from Pohukaina and transferred in a torchlight procession at night to Mauna ‘Ala, a new Royal Mausoleum in Nu‘uanu Valley. In a speech delivered on the occasion of the laying of the Cornerstone of The Royal Palace (ʻIolani Palace,) Honolulu, in 1879, JH Kapena, Minister of Foreign Relations, said:

“Doubtless the memory is yet green of that never-to-be-forgotten night when the remains of the departed chiefs were removed to the Royal Mausoleum in the valley.”

“Perhaps the world had never witnessed a procession more weird and solemn than that which conveyed the bodies of the chiefs through our streets, accompanied on each side by thousands of people until the mausoleum was reached, the entire scene and procession being lighted by large kukui torches, while the midnight darkness brought in striking relief the coffins on their biers.”

“Earth has not seen a more solemn procession what when, in the darkness of the night, the bodies of these chieftains were carried through the streets”. (Hawaiian Gazette, January 14, 1880)

In order that the location of Pohukaina not be forgotten, a mound was raised to mark the spot. After being overgrown for many years, the Hawaiian Historical Society passed a resolution in 1930 requesting Governor Lawrence Judd to memorialize the site with the construction of a metal fence enclosure and a plaque.