Transit of Venus

Interest in the heavens goes back far into the ancient fabric of Polynesian culture. Many of the early Polynesian gods derived from or dwelt in the heavens, and many of the legendary exploits took place among the heavenly bodies.

Early Polynesians, who trusted their navigational instincts and skills to the nighttime stars above, currents, winds and waves, sailed thousands of miles over open ocean across the Pacific to Hawai‘i.

They had names for their star guides: Ka Maka – the point of the fishhook in the constellation Scorpius; Makali‘i – the Little Eyes within the Pleiades; Hoku‘ula – The Red Star in the constellation Taurus; and Hokupa‘a – the North Star (fixed star,) as well as others.

After the Polynesians came, in 1778, the Europeans, under the command of Captain James Cook, arrived. He brought with him spyglasses, clocks, sextants, charts, foreign ideas and techniques – new tools of navigation.

A new awareness of the skies was reborn under the scientific patronage of King David Kalākaua, (Kalākaua reigned over the Kingdom of Hawai‘i from 1874 to 1891.)

Kalākaua had a great interest in science and he saw it as a way to foster Hawai‘i’s prestige, internationally.

The opportunity to demonstrate this interest and support for astronomy was made available with the astronomical phenomenon called the “Transit of Venus,” which was visible in Hawai‘i in 1874.

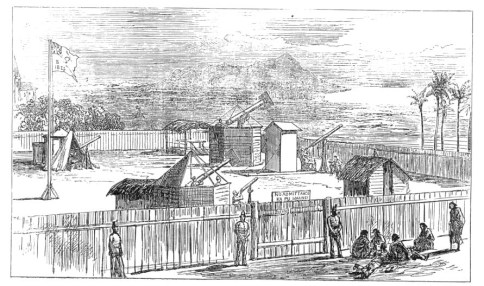

The King allowed the British Royal Society’s expedition a suitable piece of open land for their viewing area; it was not far from Honolulu’s waterfront in a district called Apua (mauka of today’s Waterfront Plaza.)

They built a wooden fence enclosure and soon a well-equipped nineteenth-century astronomical observatory took shape, including a transit instrument, a photoheliograph, a number of telescopes and several temporary structures including wooden observatories.

Subsequently, auxiliary stations – though not so elaborate as the main station in Honolulu – were established in two other island locations: one at Kailua-Kona and the other at Waimea, Kauai.

In addition, Hawai‘i was not the only site to observe the transit; under the British program, observations were also made in Egypt, Island of Rodriquez, Kerguelen Island and New Zealand. (Other countries also conducted Transit observations.)

On Dec. 8, 1874, the transit was observed by the British scientists; however, the observation at Kailua-Kona was marred by clouds. But the Honolulu and Waimea sites were considered perfect throughout the event, which lasted a little over half a day.

After the Transit of Venus observations, Kalākaua showed continued interest in astronomy, and in a letter to Captain RS Floyd on November 22, 1880, he expressed a desire to see an observatory established in Hawai‘i. He later visited Lick Observatory in San Jose.

It was not long after this that a telescope was purchased from England in 1883 and set up at Punahou School.

In 1884, the five-inch refractor was installed in a dome constructed above Pauahi Hall on the school’s campus (the first permanent telescope in Hawai‘i.)

In 1956, this telescope was installed in Punahou’s newly completed MacNeil Observatory and Science Center. (Unfortunately, it is not known where that telescope is today.

Why was the Transit of Venus important?

Although Copernicus had, by the 16th century, put the known planets in their correct order, their absolute distances remained unknown. Astronomers still needed a celestial yardstick of “Astronomical Units” with which to measure distances among the planets and to link the planets to the stars beyond.

The mission of the British expedition was to observe a rare transit of Venus across the Sun for the purpose of better determining the value of the Astronomical Unit – that is, the Earth-to-Sun distance – and from it, the absolute scale of the solar system.

The orbits of Mercury and Venus lie inside Earth’s orbit, so they are the only planets which can pass between Earth and Sun to produce a transit (a transit is the passage of a planet across the Sun’s bright disk.) Transits are very rare astronomical events; in the case of Venus, there are on average two transits every one and a quarter centuries.

Ironically, on December 8, 1874 the big day, the king was absent, being in Washington to promote Hawaiian interests in a new trade agreement with the United States.

When American astronomer Simon Newcomb combined the 18th century data with those from the 1874/1882 Venus transits, he derived an Earth-sun distance of 149.59 +/- 0.31 million kilometers (about 93-million miles), very close to the results found with modern space technology in the 20th century.