“Prostitution is one of the oldest vices of the human race, and civilized communities have been experimenting with its control for centuries. The only definite conclusion that has been reached is that it is likely to exist as long as the passions of the human beings remain what they are today.” (Police Commissioner, Victor Houston; Leder)

Given that most visitors and migrants to Honolulu were male, whether they were explorers, sailors, traders, plantation workers, military or tourists, it was only a matter of time before organized prostitution flourished in the areas surrounding their arrival and lodging near the port.

The third law of Kauikeaouli in 1835 dealt with various kinds of “illicit connections” – adultery, fornication, prostitution and rape – and specified fines ranging from ten to fifty dollars for differing offenses. (Greer)

Since the 1830s, Honolulu’s official and unofficial laws have vacillated between banning and regulating the business, which is in part why the red-light district moved between Chinatown and Iwilei. (Chinatown)

At the turn of the century and until May 1917, a segregated red-light district flourished in Iwilei. They called it the ‘Iwilei Stockade.’ Inside a high stockade wall were long rows of rooms, each 8×10; there were 225 of them. Most of the women were from Japan. From 4 pm to 2 am, the stockade gates were open. (Gallagher)

Local law enforcement condoned and controlled the activities, under the guise that it was “a public necessity.” “The whole of Iwilei makai of the Oʻahu Prison has been used for the purpose of prostitution for some time past.” (Special Legislative Committee Report, 1905)

The Iwilei brothels (or “boogie houses,” as they were also called back then) were later forced to relocate to Hotel Street and a few adjoining parts of Chinatown. By 1916, the Iwilei Stockade was shut down.

The closure of the Iwilei red-light district in conjunction with growing military presence meant that Chinatown was the red-light district for decades to come. The early-1930s saw a strictly, but unofficially, regulated industry monitored and heavily taxed by local law enforcement. Female prostitutes were both local and from the mainland. (Chinatown)

At the onset of World War II in 1941, Hawaiʻi had 258,000-civilians and 43,000-soldiers. Six months later, the number of soldiers nearly tripled. In 1944, there were approximately 400,000-military members in Hawai’i.

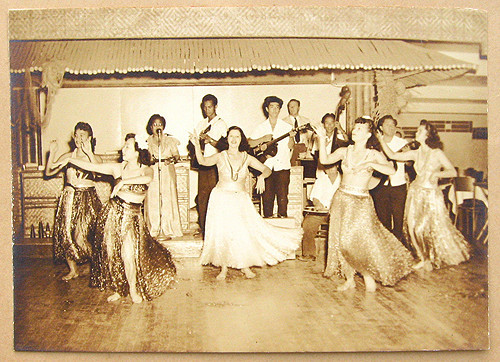

Quick to spend military paychecks before entering combat zones, men indulged in drinking, tattoos, souvenirs, massages, penny arcades, fortune telling and prostitutes within a 10-block area of Chinatown. The ‘lights-out’ policy at sunset instituted after the bombing of Pearl Harbor increased the urgency to fit in all vice activities during the day. (Chinatown)

Hotel Street was the center of Honolulu’s red light activities, through which some 30,000 or more soldiers, sailors and war workers passed on any given day during most of World War II.

Prostitution was illegal in Hawaiʻi. None-the-less, it existed as a highly and openly regulated system, involving the police department, government officials and the military. (Bailey & Farber)

During the war, approximately 250-prostitutes were registered with the Honolulu Police Department. They paid $1 a year for an “entertainers” license.

The going rate was $3 for servicemen – sessions lasted 3-minutes. Of the $3 charge, the madam took $1 off the top; the prostitute paid for room, board and laundry from her $2 cut.

Most houses operated officially from 8 am to noon. Most brothels required girls to see at least 100-men a day and to work at least 20 days per month. They could make $30,000 to $40,000 per year (versus the average working woman’s typical $2,000.)

The majority of official Honolulu prostitutes were white women recruited through San Francisco. Each prostitute arriving from the mainland was met at the ship by a member of the vice squad; she was then fingerprinted and given a license.

There were rules to follow; breaking them could result in a beating or removal from the Islands. Few lasted more than 6-months before heading back to the West Coast.

While Hotel Street had the reputation as the home of the brothels, most of the houses were in an area bounded by Kukui, Nuʻuanu, Hotel and River streets.

During the war years, fifteen brothels operated in this section of Chinatown, their presence signaled by neatly lettered, somewhat circumspect signs (‘The Bronx Rooms,” “The Senator Hotel,” “Rex Rooms”) and by the lines of men that wound down the streets and alleyways.

On September 10, 1944, Governor Stainback sent the following to Ferris F Laune, the council’s secretary: “I have … requested the Police Commission to take steps to close and keep closed the existing houses of prostitution in the City and County of Honolulu.” The Police Commission instructed closure of the houses on September 24. (Greer)

It hasn’t gone away; today, anyone engaged in prostitution – as a prostitute or as a client – faces a petty-misdemeanor charge, and first-time offenders, if not granted a deferred judgment, can be fined not less than $500 but not more than $1,000, or spend up to 30 days in jail, or be sentenced to probation. Subsequent offenses have higher penalties. (HRS 712-1200)