by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

by Peter T Young 2 Comments

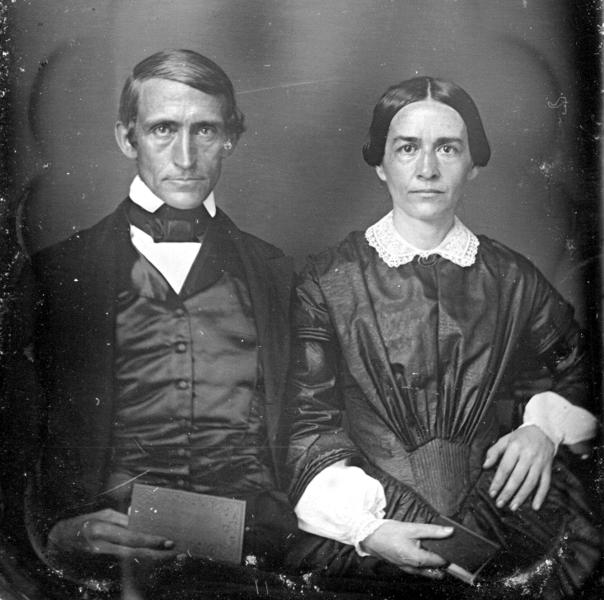

Daniel Dole was born in Bloomfield (now Skowhegan,) Maine, September 9, 1808. He graduated from Bowdoin College in 1836 and Bangor Theological Seminary in 1839, and then married Emily Hoyt Ballard (1807-1844,) October 2, 1840 in Gardiner, Maine.

The education of their children was a concern of missionaries. There were two major dilemmas, (1) there were a limited number of missionary children and (2) existing schools (which the missionaries taught) served adult Hawaiians (who were taught from a limited curriculum in the Hawaiian language.)

During the first 21-years of the missionary period (1820-1863,) no fewer than 33 children were either taken back to the continent by their parents. (Seven-year-old Sophia Bingham, the first Caucasian girl born on Oʻahu, daughter of Hiram and Sybil, was sent to the continent in 1828. She is my great-great-grandmother.)

On July 11, 1842, fifteen children met for the first time in Punahou’s original E-shaped building. The first Board of Trustees (1841) included Rev. Daniel Dole, Rev. Richard Armstrong, Levi Chamberlain, Rev. John S Emerson and Gerrit P Judd. (Hawaiian Gazette, June 17, 1916)

By the end of that first year, 34-children from Sandwich Islands and Oregon missions were enrolled, only one over 12-years old. Tuition was $12 per term, and the school year covered three terms. (Punahou)

By 1851, Punahou officially opened its doors to all races and religions. (Students from Oregon, California and Tahiti were welcomed from 1841 – 1849.)

December 15 of that year, Old School Hall, “the new spacious school house,” opened officially to receive its first students. The building is still there and in use by the school.

“The founding of Punahou as a school for missionary children not only provided means of instruction for the children, of the Mission, but also gave a trend to the education and history of the Islands.”

“In 1841, at Punahou the Mission established this school and built for it simple halls of adobe. From this unpretentious beginning, the school has grown to its present prosperous condition.” (Report of the Superintendent of Public Education, 1900)

The curriculum at Punahou under Dole combined the elements of a classical education with a strong emphasis on manual labor in the school’s fields for the boys, and in domestic matters for the girls. The school raised much of its own food. (Burlin)

Some of Punahou’s early buildings include, Old School Hall (1852,) music studios; Bingham Hall (1882,) Bishop Hall of Science (1884,) Pauahi Hall (1894,) Charles R. Bishop Hall (1902,) recitation halls; Dole Hall and Rice Hall (1906,) dormitories; Cooke Library (1908) and Castle Hall (1913,) dormitory.

Dole Street, laid out in 1880 and part of the development of the lower Punahou pasture was named after Daniel Dole (other nearby streets were named after other Punahou presidents.)

Emily died on April 27, 1844 in Honolulu; Daniel Dole married Charlotte Close Knapp (1813-1874) June 22, 1846 in Honolulu, Oʻahu.

Daniel Dole resigned from Punahou in 1855 to become the pastor and teacher at Kōloa, Kauai. There, he started the Dole School that later became Kōloa School, the first public school on Kauai. Like Punahou, it filled the need to educate mission children.

The first Kōloa school house was a single room, a clapboard building with bare timbers inside and a thatched roof. Both missionary children as well as part-Hawaiian children attended the school. (Joesting)

Due to growing demand, the school was enlarged and boarding students were admitted. Reverend Elias Bond in Kohala sent his three oldest children to the Kōloa School, as did others from across the islands. (Joesting)

Charlotte died on Kauai in 1874 and Daniel Dole died August 26, 1878 in Kapaʻa, Kauai. Dole’s sons include Sanford Ballard Dole (President of the Republic of Hawaiʻi and 1st Territorial Governor of Hawaiʻi.) Daniel Dole was great uncle to James Dole, the ‘Pineapple King.’

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

Prior to contact (1778,) Royal Centers served as the rulers’ residence and governing location. Aliʻi moved between several residences throughout the year; each served as his Royal Center and place of governance.

Typically such Royal Centers contained the ruler’s residence, residences of high chiefs, a major heiau (which became increasing larger in size in the AD 1600s-1700s,) other heiau and often a refuge area (puʻuhonua).

The Royal Centers were selected for their abundance of resources and recreation opportunities, with good surfing and canoe-landing sites being favored.

On August 21, 1959 Hawaiʻi became the 50th state.

Today, we reference the location of the governing seat as the ‘capital’ and official statehouse as its ‘capitol.’

The present Hawaiʻi capitol building opened in 1969. Prior to that time, from about 1893 to 1969, ʻIolani Palace served as the statehouse.

After the overthrow in 1893, the Provisional Government first established its offices in the Aliʻiolani Hale; after a few months, the governmental offices were transferred to ʻIolani Palace (that later building’s name was temporarily changed to the “Executive Building” – the name “ʻIolani Palace” was restored by the Legislature in 1935.) (NPS)

The former throne room had been used for sessions of the Territorial House of Representatives. The state dining room was used as the chamber of the Territorial Senate. The private apartment of Kalākaua and later Liliʻuokalani was used as the Governor’s office. (NPS)

The location of the present Capitol was selected in 1944. In 1959, an advisory committee was formed. They selected the Honolulu firm of Belt, Lemmon & Lo and the San Francisco firm of John Carl Warnecke & Associates to design the new state capitol.

Their design was approved by the Legislature in 1961; construction commenced in November 1965. The building opened on March 16, 1969, replacing the former statehouse, ʻIolani Palace.

To quote from an address given by Governor John A. Burns, “The open sea, the open sky, the open doorway, open arms and open hearts – these are the symbols of our Hawaiian heritage. In this great State Capitol there are no doors at the grand entrances which open toward the mountains and toward the sea. There is no roof or dome to separate its vast inner court from the heavens and from the same eternal stars which guided the first voyagers to the primeval beauty of these shores.”

“It is by means of the striking architecture of this new structure that Hawaii cries out to the nations of the Pacific and of the world, this message: We are a free people……we are an open society……we welcome all visitors to our island home. We invite all to watch our legislative deliberations; to study our administrative affairs; to see the examples of racial brotherhood in our rich cultures; to view our schools, churches, homes, businesses, our people, our children; to share in our burdens and our self-sorrows as well as our delights and our pleasures. We welcome you! E Komo Mai! Come In! The house is yours!”

The building is full of symbolism: the perimeter pool represents the ocean surrounding the islands; the 40-concrete columns are shaped like coconut trees; the conical chambers infer the volcanic origins of the Islands; and the open, airy central ground floor suggests the Islands’ open society and acceptance of our natural and cultural environment.

There are eight columns in the front and back of the building; groups of eight mini-columns on the balcony that surrounds the fourth floor; and eight panels on the doors leading to the Governor’s and Lieutenant Governor’s chambers – all symbolic of the eight main islands.

The Hawaiʻi State Capitol is a five-story building with an open central courtyard. According to the architects, “The center of the building, surrounded by a ring of columns, is a great entrance well open on all sides at ground level and reaching upward through four floors of open galleries to the crown canopy and the open sky. Visitors can walk directly into the spectators’ galleries overlooking the House and Senate chambers situated at ground level, and they can reach any of the upper floors by elevators.”

Caucus rooms, clerks’ and attorneys’ offices, a library, a public hearing room, and suite for the President are at the Chamber level. The three legislative office floors (2-4) are of similar design, with peripheral offices for the legislators.

The suites for the Governor and Lieutenant Governor are on the uppermost floors, overlooking the sea on the outside and the courtyard on the inside. Public circulation on the upper floors is through lanais that overlook the court. Parking is provided in the basement.

The Capitol building is a structure of steel reinforced concrete and structural steel. The building is rectangular with dimensions of 360 feet x 270 feet (although it is often referred to as the “Square Building on Beretania.”) It is 100-feet high. (Lots of info here from NPS.)

by Peter T Young 1 Comment

In 1903 President Theodore Roosevelt announced that the U.S. would complete a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, begun years earlier by a French company.

The canal would cut 8,000 miles off the distance ships had to travel from the east coast to the west. No canal of this scale had been built before, and many said it could not be done.

At the turn of the 20th Century, San Francisco was the largest and wealthiest city on the west coast of the United States. In 1906, a disastrous earthquake struck San Francisco. The ensuing fire was more devastating than the Chicago fire of 1871.

Less than 10 years after most of San Francisco was destroyed, the proud city was rebuilt and its people were ready to hold a party, one designed to dazzle the world and showcase the new city.

Even as San Francisco was rebuilding after the earthquake, local boosters promoted the city in a competition to host a world’s fair that would celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal.

The new San Francisco was the perfect choice, and Congress selected the city over several other aspirants, including New Orleans and San Diego.

In order to build this grand fair, over 630 acres of bayfront tidal marsh, extending three miles from Fort Mason to east of the Golden Gate (today’s Marina District and Crissy Field), were filled.

On this new land, 31 nations from around the world and many US states built exhibit halls, connected by 47-miles of walkways. There were so many attractions that it was said it would take years to see them all.

Locals simply called it ‘The Fair.’

For nine months in 1915, the Presidio’s bayfront and much of today’s Marina District was the site of a grand celebration of human spirit and ingenuity. Hosted to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition reflected the ascendancy of the US to the world stage and was a milestone in San Francisco history.

Over 18-million people visited the fair; strolling down wide boulevards, attending scientific and educational presentations, “travelling” to international pavilions and enjoying thrilling displays of sports, racing, music and art. The fair promoted technological and motor advancements.

It was the first world’s fair to demonstrate a transcontinental telephone call, to promote wireless telegraphy and to endorse the use of the automobile. Each day, the fair highlighted special events and exhibits, each with their own popular souvenirs.

The fair was so large and spread out over such a length of land that it was virtually impossible for any visitors to successfully see it all, even over the course of several visits.

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition looked to the future for innovation. Things we take for granted today – cars, airplanes, telephones, and movies – were in their infancy and were shown off at the fair, and some well-known technological luminaries were involved in the fair.

Henry Ford, who brought mass production to American manufacturing and made the automobile affordable to middle class society, built an actual Model T assembly line at the fair. Fords were produced three hours a day, six days a week.

New farming and agricultural technologies were also introduced at the fair. Luther Burbank, creator of many new kinds of plants including the Burbank potato, Santa Rosa plum, Shasta daisy, and the fire poppy, was in charge of the Horticulture Palace.

Author Laura Ingalls Wilder was particularly impressed with new dairy techniques. She wrote, ‘I saw…cows being milked with a milk machine. And it milked them clean and the cows did not object in the least.’

The scale and design of the fair were exceptional. The Palace of Machinery, the largest structure in the world at the time, was the first building to have a plane fly through it. The Horticulture Palace had a glass dome larger than Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

The Tower of Jewels reached 40 stories skyward and held 102,000 pieces of multicolored cut glass that sparkled by day and were illuminated by intense electric lights at night. When the fog came in, 48 spotlights of seven different colors illuminated the sky to look like the northern lights.

The physical structures of the fair were built to be temporary. Most were torn down shortly after the fair closed. However, a few reminders of the fair remain. The railway tunnel under Fort Mason and the San Francisco Yacht Harbor still exist, and the shape of an old race track may be seen on perimeter of the grass Crissy airfield.

The most impressive remnant of all is the Palace of Fine Arts. This landmark, much loved by San Franciscans and visitors from around the world, was spared demolition and was restored and reinforced in the 1960s. It continues to dazzle many millions of people each year. (NPS)

A few agencies and municipalities purchased the smaller buildings that could be transported by boat to new locations. San Mateo County purchased the Ohio Building; Marin County purchased the Wisconsin and Virginia Buildings; the army maintained the Oregon Building on its Presidio location as a military clubhouse.

Some of the larger buildings that were too big to move, like the Tower of Jewels, were disassembled and sold to scavengers. Unfortunately, because the fair buildings were only constructed of plaster, faux travertine and chicken wire, they did not last as long as permanent buildings; once the buildings reached a serious level of deterioration, they were demolished. (NPS)

One of the most popular attractions at the Exposition was a daily show at the Hawaiian Pavilion featuring Hawaiian musicians and hula dancers. It’s where millions of people heard the ‘ukulele for the first time. (Mushet)

“Kamehameha Day at the exposition, or Hawaii Day as they called it here, was all that had been hoped for it. There was splendid weather; the water pageant and the singing of Hawaiian music made a deep sentimental and esthetic effect, and the program as a whole drew tremendous crowds.” (Hawaiian Gazette, June 15, 1915)

At the corner of what is now Baker Street and Marina Boulevard in San Francisco’s Marina District was where the Hawaiian Pavilion stood during the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

These Hawaiian shows had the highest attendance at the entire fair and launched a Hawaiian cultural craze that influenced everything from American music, to movies, to fashion. (Mushet)

“The hugely popular Hawaii pavilion … showcased Hawaiian music and hula dancing, and was the unofficial launching pad for ukulele-mania.” Hapa-haole songs were featured in the Hawaii exhibits.

“After the expo, Tin Pan Alley and jazz writers and musicians took interest in the cheery little instrument. Songs such as “Ukulele Lady” and “Oh, How She Could Yacki Hacki Wicki Wacki Woo (That’s Love in Honolulu)” were published in sheet-music format.”

“Guitar maker CF Martin & Co. built more ukuleles in 1926 than in any previous year. But the uke’s popularity, along with Martin’s production of the instrument, dwindled in the 1930s.” (San Francisco Examiner)

Everyone began writing hapa-haole songs, and in 1916, hapa-haole recordings outsold other types of music. Over the decades they were written in all popular styles—from ragtime, to 30’s swing, to 60s surf-rock. (Ethnic Dance Festival, 2015)

The Panama Pacific International Exposition closed in November 1915. It succeeded in buoying the spirits and economy of San Francisco, and also resulted in effective trade relationships between the US and other nations of the world. (Lots of information here is from NPS.)

by Peter T Young 2 Comments

Marines and Sailors trained for what has been referred to as the toughest marine offensive of WWII. 1,300 miles northeast of Guadalcanal, the Japanese had constructed a centralized stronghold force in a 20-island group called Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands.

The Marines would reconstitute at Camp Tarawa at Waimea, on the Island of Hawaiʻi. Originally an Army camp named Camp Waimea, when the population in town was about 400, it became the largest Marine training facility in the Pacific following the battle of Tarawa.

Huge tent cities were built on Parker Ranch land; the public school and the hotel across the road from it were turned into a 400-bed hospital. At first the school children attended classes in garages and on lanais, but by fall of 1944, Waimea School was housed in new buildings built by Seabees on the property behind St. James’ church.

Over 50,000-servicemen trained there between 1942 and 1945; it closed in November 1945. The new roads, reservoirs and buildings were left to the town. The public school children returned to Waimea School, and the buildings behind St. James’ stood empty … but not for long.

At the end of World War II, the Right Reverend Harry S Kennedy arrived. He was a builder of congregations and of schools, and when he saw the empty buildings at St. James’, he immediately saw possibilities.

March 12, 1949, Bishop Kennedy and a group of local businessmen turned the buildings into a church-sponsored boarding school for boys, Hawaiʻi Episcopal Academy. The Episcopal priest was both headmaster of the school and vicar of St. James’ Mission.

The early school struggled with facilities and financing. A turning point came in 1954, when James Monroe Taylor left Choate School in Connecticut to become HPA headmaster.

Three years later, substantial financial pledges came in and the church surrendered its direction to a new governing board. The school was then independently incorporated and the name changed to Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy.

In January 1958, the board of governors purchased 55-acres of land in the foothills mauka of the Kawaihae-Kohala junction and announced plans to build a campus there. Within a year, two dorms opened on the new campus and another was cut and moved from the town campus.

Old Air Force buses driven by faculty members made daily runs between the new campus, where boarders ate and slept, and the old campus, where classes were held. The last class to graduate on the town campus was the Class of 1959.

Honolulu architect Vladimir N Ossipoff was retained to design the campus buildings – five classroom buildings, two residence halls, a chapel, a library, an administration building and a dining commons.

In 1976, HPA acquired the buildings of the former Waimea Village Inn in town. Growing out of the “Little School” founded in 1958 by Mrs T to accommodate children of HPA faculty in the lower grades, the Village Campus today houses HPA’s Lower and Middle Schools, encompassing kindergarten through eighth grade.

In the 1980s, 30-acres of Parker Ranch land were added to the Upper Campus. Besides the Village Campus, the school added the Institute for English Studies and a campus in Kailua-Kona for grades K-5. (The Kona campus became the independent Hualālai Academy, but it closed effective May 30, 2014.)

Building projects expanding the HPA facilities included Atherton House, the headmaster’s residence, Gates Performing Arts Center, Dowsett Pool, Gerry Clark Art Center, Davenport Music Center, Kō Kākou Student Union, faculty housing and the Energy Lab.

Starting with five boarding students in a World War II building, today, there are 600 students (approximate annual enrollment) – 200 in Lower and Middle Schools (100% day students) – 400 in Upper School (50% day, 50% boarding) ; Boarding students: 60% U.S., 40% international.

HPA is fully accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges and is a member of 12 educational organizations including the Council for the Advancement and Support of Education, College Entrance Examination Board, Council for Spiritual and Ethical Education, Cum Laude Society, National Association of College Admission Counselors, Hawaii Association of Independent Schools, and National Association of Independent Schools. (Information here from HPA and St James.)

I am one of the fortunate boys-turned-to-young-men under the leadership and guidance of headmaster Jim Taylor.