Georges Trousseau was born in Paris on May 1, 1833 to a prominent Parisian family. His father, Armand Trousseau, a distinguished physician and surgeon, was also the author of medical books used throughout the world. (Greenwell)

He received the usual education of a wealthy Frenchman and entered the ecole de medicine in Paris at the early age of 15. (Hawaiʻi Holomua, May 5, 1894)

From the days in 1848 and 1852, when he as a student fought in the streets of Paris, he has unswervingly believed in the rights of the people – and early or late was he found ready to serve them as a physician as a friend or simply as a fellow-man. (Hawaiʻi Holomua, May 5, 1894)

Trousseau married Edna Vaunois, who was also from Paris; they had two children, Armond and Rene in 1856 and 1857. In 1865, the couple was legally separated (but never divorced.)

He followed his father’s footsteps and graduated from the Paris School of Medicine as a physician in 1858. He became an army surgeon, seeing service in Algiers early in the fifties. He also served at Solferino and Magenta, Italy. (Greenwell)

For personal reasons, he left France and went to Australia and New Zealand. In part, he was at the Australian gold mines, but did not strike it rich; in fact, his estranged wife loaned him money while he was there. (Greenwell, Hawaiʻi Holomua, May 5, 1894)

He left there and arrived in Hawaiʻi in 1872. Almost immediately upon his arrival, he was appointed by the Board of Health to serve as Port Physician for Honolulu (there was no salary attached to the office; fees for services were worked out between the Port Physician and the ship/agent the usual charge was $25.) (Greenwell)

He soon gained great fame as a doctor. He served on the Board of Health for 20-years, serving as a Board member and as President. He took an interest in Leprosy and supervised the leper treatment center in Kalihi.

In 1865, the legislature of the Hawaiian Islands had passed “An Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy.” This law called for a place to be set aside for the isolation of those found to have leprosy in order to curb the spread of the disease. It was not until 1873, however, on Doctor Trousseau’s recommendation, that a vigorous effort was made to segregate lepers. (Greenwell)

“Trousseau strongly urging that the only method, at all likely to be successful, was the immediate, energetic, and to a certain extent, unsympathetic isolation of all who were afflicted with the disease, and even that would require a generation in all probability to prove successful.” (Board of Health, March 1, 1873)

He diagnosed Father (now Saint) Damien’s leprosy. “… In January, 1885 Damien visited Honolulu … (and accidentally) scalded his left foot. Father Leonore, the provincial of the mission, phoned for Dr George Trousseau, whose examination of the priest’s foot and leg proved they were devoid of feeling … this discovery indicated that the peroneal nerve and its branches were dead due to leprosy.” (Mouritz; Bushnell)

Though not an official title, Trousseau served as royal physician. He was called on as a consultant by Doctor Ferdinand W Hutchison, Minister of the Interior, during Kamehameha V’s last illness and was at the King’s bedside when he died.

In August 1873, when it was apparent that King Lunalilo was ill, Trousseau accompanied the King and stayed with Lunalilo at Huliheʻe Palace in Kailua- Kona, from mid-November to the middle of January 1874. After it became apparent that Lunalilo was not going to recover, and the royal party returned to Honolulu where Lunalilo died on February 3. (Greenwell)

The rulers of Hawaiʻi honored him. Lunalilo made him a major in his staff and his personal physician. Kalākaua befriended him and appointed him the executor of his will and the administrator of his estate. (Hawaiʻi Holomua, May 5, 1894)

“(H)e was always ready to promote any now industry that might prove a source of benefit to his adopted country.” This got him involved in sheep, sugar and ostriches. (Hawaiʻi Holomua, May 5, 1894)

In 1875, he gave up his Honolulu medical practice and moved to Kona, Hawaiʻi, where he purchased a sheep and cattle ranch at Kanahaha high on the slopes of Mauna Loa. Wool was baled at Kanahaha and transported by cart to Kainaliu Beach, from where it was shipped. (Greenwell)

A road was constructed which ran from Kanahaha on Mauna Loa, to the beach at Kainaliu (where he also had a home.) (This old cart road is used by jeeps today and is known as the Trousseau Trail.) Early in 1879, Trousseau sold all of his holdings in Kona to Henry N Greenwell.

After selling the sheep ranch, Trousseau bought out two sugar planters at Kukuihaele on the Hāmākua coast. He became partners in the Pacific Sugar Mill with the Purvis family. Trousseau had an excellent relationship with John Purvis and his son Herbert. (Greenwell)

The plantation thrived for a time. However, defects in the furnace caused difficulties. In 1881, Trousseau suddenly and unexpectedly sold his half in the plantation to his partners. He moved back to Honolulu and resumed his medical practice.

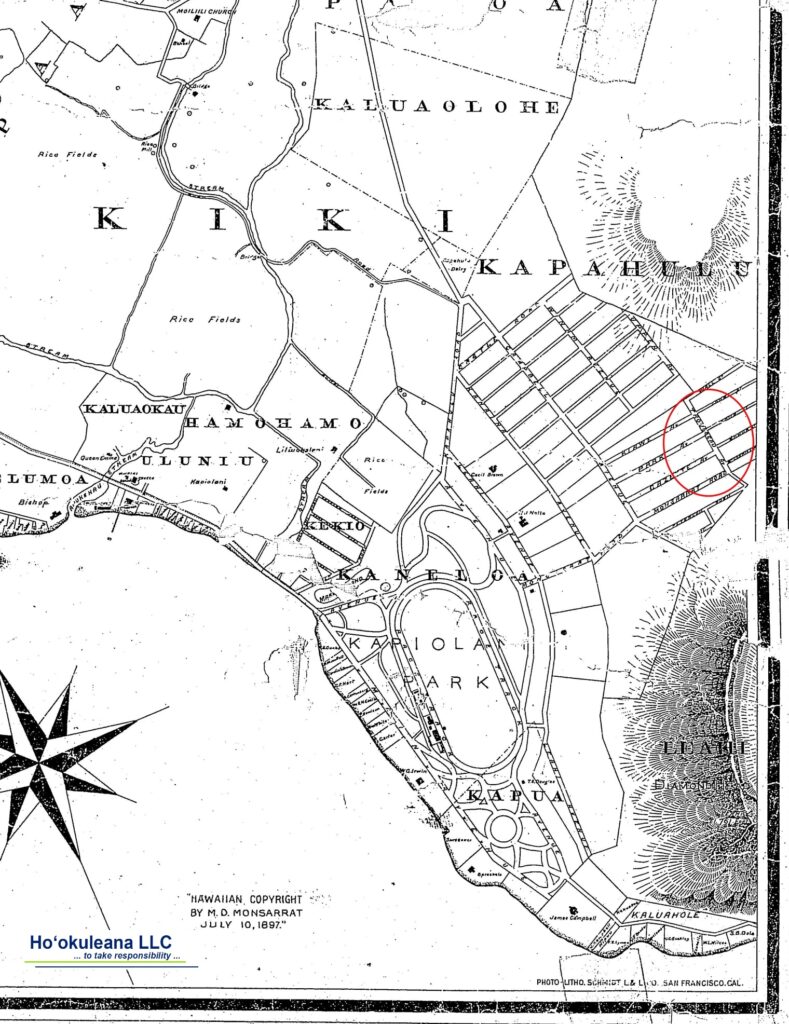

He tried one last agricultural venture there. “The doctor started a new industry for these islands a few years ago (1890) by establishing an ostrich farm at Kapiʻolani Park. Many young birds have been bred from the original stock, and some of the feathers have gone into domestic exports. The farm was under the management of Captain John Morriseau (Trousseau’s nephew.)” (Daily Bulletin, May 5, 1894)

The 1,000-acre farm (purchased from the Lunalilo Estate) was located in the Kapahulu area near the present zoo; Paul Isenberg, who owned a nearby cattle ranch, later purchased the farm (Trousseau Street notes the general location.)

Though Trousseau never divorced, he did have a mistress, Makanoe; Makanoe was also married (to Kaʻaepa.) (This relationship is referred to as ‘punalua;’ an association in which, typically, two women, often sisters, share one husband, or, as in Makanoeʻs case, two men share the affection of one woman.) (Greenwell)

Trousseau died May 4, 1894, shortly after Kaʻaepa’s death. Makanoe buried her husband and Trousseau side by side in a wrought iron fenced plot at Makiki Cemetery on Oʻahu. Trousseau left all of his estate to Makanoe (she eventually moved to Salt Lake City, Utah.)

Trousseau faithfully supported the Hawaiian Monarchy and stood up for the royalists which caused bitter feelings among many of his associates who backed the annexationists.

In spite of this, his obituary noted, “It is seldom that people of all classes, opposed to each other socially and politically can gather around the bier of a fellow-citizen and unite in saying, ‘we have lost a friend.’” (Hawaiʻi Holomua, May 5, 1894)

“Dr. Trousseau was a strong nationalist of Hawaiʻi, who believed that none but born or naturalized subjects should have a determining voice in national affairs. The Hawaiian people, who revered and confided in him, will take his death as a sort bereavement.” (Daily Bulletin, May 5, 1894) (Lots of information here from Jean Greenwell.)