“William Bradford his wife dyed soone after their arrival” (Bradford)

Dorothy May was born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England, about 1597, the daughter of Henry and Katherine May. She was the niece of Mayflower passenger William White (her grandmother Thomasine (Cross)(May) White was also the mother of William White). (Caleb Johnson)

The May family moved to Amsterdam around 1608 and Henry May was a leading church elder in the Henry Ainsworth church congregation in the city.

At the age of 16, she married 23-year old William Bradford in Amsterdam, and returned with her husband to take up residence in Leiden, Holland. (Caleb Johnson)

Then appeared also as before William Bradford [noted as Willem Braetfort], from Austerfield, fustian weaver, 23 years old, living at Leyden, where the banns have been published, declaring that he has no parents, on the one part, and Dorothy May [noted as Dorethea Maije], 16 years old, from Wisbeach in England, at present living on the New Dyke, assisted by Henry May, on the other part …

and declared that they were betrothed to one another with true covenants, requesting their three Sunday proclamations in order after the same to solemnize the aforesaid covenant and in all respects to execute it, so far as there shall be no lawful hindrances otherwise. And to this end they declared it as truth that they were free persons and not akin to each other by blood

That nothing existed whereby a Christian marriage might be hindered; and their banns are admitted. (The Mayflower Descendant, Bowman, Mayflower Marriage Records at Leyden and Amsterdam, April 1920)

The record of the marriage intentions of William Bradford and Dorothy May, at Amsterdam, is not dated, but it follows one dated 9 November 9, 1613. The marriage took place at Amsterdam, December 10, 1613 and was recorded in the Pui Book. (The Mayflower Descendant)

Dorothy and William Bradford had a son, John, who was born in Leiden sometime around 1617. When William and Dorothy decided to make the voyage to America in 1620 on the Mayflower, they left John behind in Leiden with Dorothy’s parents. (Caleb Johnson) Bradford notes the son ‘came afterward”. (Bradford)

On September 6 (September 16), 1620, the Mayflower departed from Plymouth, England, and headed for America. The first half of the voyage went fairly smoothly, the only major problem was sea-sickness. But by October, they began encountering a number of Atlantic storms that made the voyage treacherous.

The voyage itself across the Atlantic Ocean took 66 days, from their departure on September 6 (September 16). On the way and just 3-days from their arrival at Cape Cod, William Butten was the first Mayflower passenger to die. He was believed to have been sick for much of the two-month voyage.

Bradford recorded: “in all this voyage there died one of the passengers, which was William Butten, a youth, servant to Samuel Fuller, when they drew near the coast”. He was a “youth,” as noted by William Bradford and a servant of Samuel Fuller.

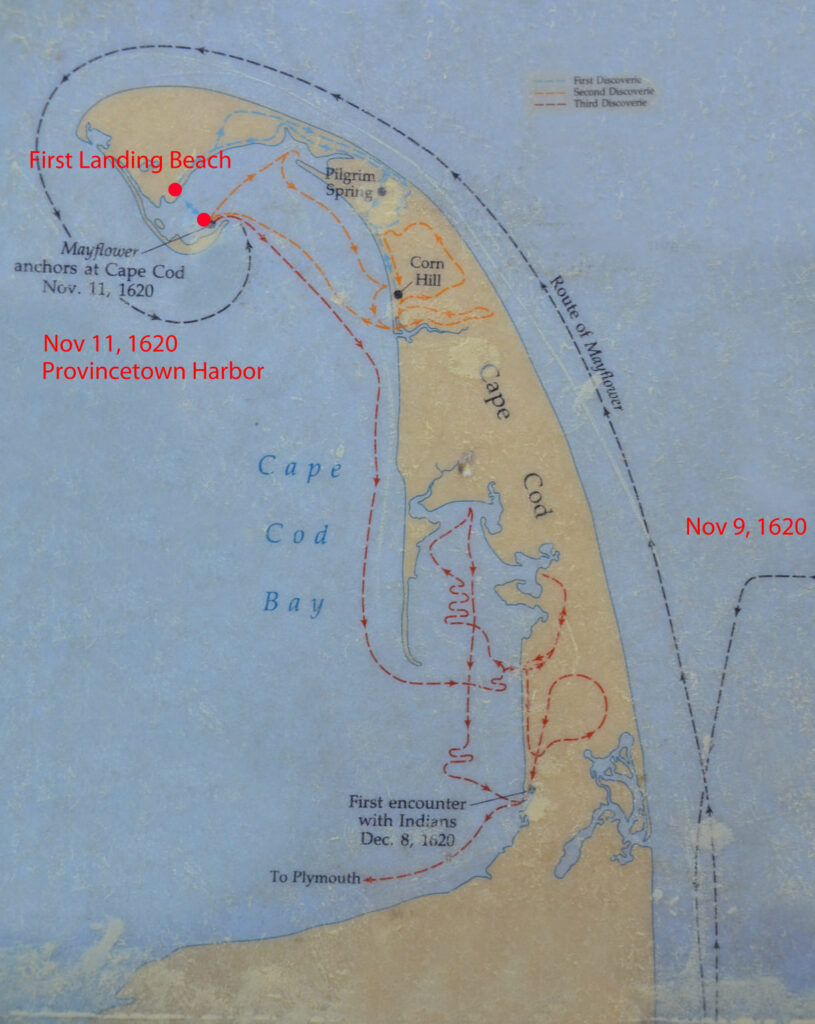

November 9 (November 19), 1620 they sighted Cape Cod. Of the arrival, Bradford wrote, “Being thus arived in a good harbor and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees & blessed ye God of heaven, who had brought them over ye vast & furious ocean, and delivered them from all ye periles & miseries therof, againe to set their feete on ye firme and stable earth, their proper elemente.”

“And no marvell if they were thus joyefull, seeing wise Seneca was so affected with sailing a few miles on ye coast of his owne Italy; as he affirmed, that he had rather remaine twentie years on his way by land, then pass by sea to any place in a short time; so tedious & dreadfull was ye same unto him.”

“But hear I cannot but stay and make a pause, and stand half amased at this poore peoples presente condition; and so I thinke will the reader too, when he well considered ye same.”

“Being thus passed ye vast ocean, and a sea of troubles before in their preparation (as may be remembred by yt which wente before), they had now no friends to wellcome them, nor inns to entertaine or refresh their weatherbeaten bodys, no houses or much less townes to repaire too, to seeke for succoure. …”

“Let it also be considred what weake hopes of supply & succoure they left behinde them, yt might bear up their minds in this sade condition and trialls they were under; and they could not but be very smale.”

“It is true, indeed, ye affections & love of their brethren at Leyden was cordiall & entire towards them, but they had litle power to help them, or them selves; and how ye case stode betweene them & ye marchants at their coming away, hath already been declared.”

“What could not sustaine them but ye spirite of God & his grace? May not & ought not the children of these fathers rightly say:”

“Our faithers were Englishmen which came over this great ocean, and were ready to perish in this willdernes; but they cried unto ye Lord, and he heard their voyce, and looked on their adversitie…”

Then, Pilgrims started to die.

Edward Thompson died December 4/14, 1620, and was the first person to die after the Mayflower arrived in America. This was several weeks before the Pilgrims located and made plans to settle at Plymouth. He was a servant of William White.

Others died, typically of sickness … Jasper More was a 7-year-old boy from Shropshire and a servant of John Carver. Bradford recorded that Jasper died “of the common infection” on 6/16 December. James Chilton. He was about 64 years old and a Separatist from Leiden. He died on December 8/18 and William Bradford wrote that he died in the First Sickness.

Tragedy struck the Bradford household. Bradford simply wrote, “William Bradford his wife dyed soone after their arrival”.

Dorothy Bradford was about 23 years old. On December 7/17, 1620, she possibly slipped, falling from the deck of the Mayflower and drowning in the icy water of Cape Cod harbor. This happened while her husband was ashore with an expedition.

Mather wrote of Bradford and his wife, “his dearest consort accidentally falling overboard, was drowned in the harbour ; and the rest of his days were spent in the services, and the temptations, of that American wilderness.” (Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana)

Within weeks, fifty-two of the 102 passengers who had reached Cape Cod were dead, including fourteen of the twenty-six heads of families. All but four families had lost at least one member. Of the eighteen married couples who had sailed from England, only three had survived intact.

William Bradford married again, in 1623, to Alice Southworth. They had three children.

Click the following link to a general summary about Dorothy Bradford:

https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/wp-content/uploads/Dorothy-Bradford.pdf