“For ten days or more the movements of certain parties have been subjected to very close scrutiny. Though without their knowledge they have been under careful surveillance.”

“Reports by the police are to the effect that an uprising was scheduled for Saturday night. The capture of the Executive building was not to be undertaken until very late. President Dole and his Cabinet Ministers were to be taken prisoners. At the same time the insurgents were to take possession of the Police Station.”

“At 10 o’clock Lieutenant Holi was dispatched for Joseph Nāwahī. He was found at his home at Kapalama. He reached the station house twenty minutes later. The charge against Mr. Nāwahī was treason. He was given a cell all to himself. No bondsman appeared on behalf of Mr Nāwahī.” (Hawaiian Star, Dec 10, 1894)

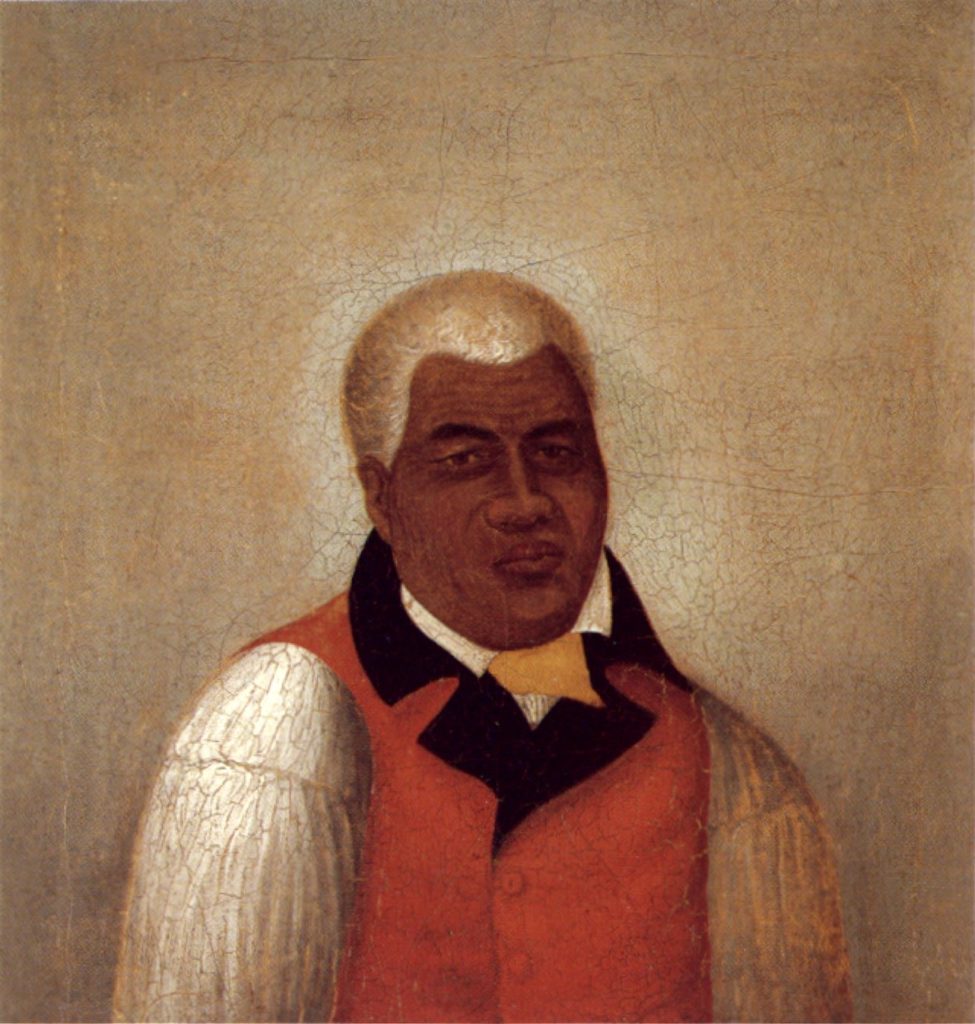

“Born in 1842 at Kaimū, his parents named him Joseph Kahoʻoluhi Nāwahīokalaniʻōpuʻu. Raised by his uncle, Joseph Paʻakaula, twelve-year-old Nāwahī enrolled in Hilo Boarding School. His first teachers were Rev. David and Sarah Lyman.”

“In July 1856 Nāwahī became a seminary student at Lahainaluna, Maui and finally a scholar at the Royal School in Honolulu. His career included periods as a teacher, assistant principal, and briefly principal at Hilo Boarding School. He also chose to work as a surveyor, lawyer, and newspaper publisher.”

“Nāwahī served many years for the Kingdom government: as a representative for the people of Puna (1872–1876), then Hilo (1878–1884, 1890–1893) and as Minister of Foreign Affairs for Queen Liliʻuokalani.” (Lyman Museum)

He spent nearly three months in jail before his supporters were able to raise the money and bail him out, where it is believed he contracted tuberculosis. (Oiwi TV and Ka‘iwakīloumoku)

At the trial, “When the jury were out two hours they came out for instructions. They retired again and at 8 o’clock returned a verdict of not guilty for Nawahi …. Judge Cooper discharged Mr Nawahi and, thanking the jury for their close attention, dismissed them ….” (The Independent. May 10, 1895)

Following his imprisonment, he founded the Hui Aloha ʻĀina political party [a patriotic group created to support Lili‘uokalani and oppose annexation] and published the newspaper Ke Aloha ʻĀina. (Lyman Museum)

He was ill; “Mr and Mrs Joseph Nawahi will leave for the coast by the Alameda. Mr Nawahi has been quite ill recently and his physician advised a sea voyage.” (The Independent, August 19, 1896)

“Joseph Nawahi, one of the ablest Hawaiian members of the Honolulu bar, died in San Francisco from consumption [Tuberculosis] on the 14th inst. [September 14, 1896]”

“He had been in failing health here for some time, and visited California in the hope that a change of climate would benefit him, but his weakened condition left him without the means to combat the disease. … His remains will be returned to Honolulu on Monday by the SS Australia. Deceased leaves a widow and two sons. (PCA, Sept 25, 1896)

“The two native societies Aloha Aina and Kalaiaina had made arrangements with undertaker EA Williams to take charge of the remains of Joseph Nawahi on their arrival on the Australia”.

“The wharf was crowded to suffocation with some three or four thousand natives who had intended to follow the hearse after the two societies.” (Evening Bulletin, Sep 29, 1896)

“The body was carried to the undertaking parlors of HH Williams, and about noon conveyed in a hearse drawn by four bay horses to the Nawahi’s residence at Palama where the last respects were paid to the deceased patriot by his mourning compatriots.”

“Mrs Nawahi, the widow, brought her husband’s body from San Francisco to his island home and was received at the wharf by her grief-stricken sons and relatives.”

“The casket containing the remains was wrapped in a Hawaiian flag and numerous floral offerings were sent to the house during the day.”

“The remains will be sent to Hilo tomorrow afternoon by the steamer Hawaii for interment, after the services have been held at 12:30 pm at the homestead.” (The Independent, Sep 29, 1896)

“Excitement ran high in [Hilo] when a telephone message from Purser Beckley of the Kinau, sent from Kawaihae early Wednesday morning last, announced that the body of the late Joseph Nawahi would arrive here on the steamer Hawaii, to leave Honolulu on that same day.”

“The mere fact that the arrival of the Hawaii was a matter of conjecture, due to the large amount of freight for Lahaina and other way ports, increased the excitement to a still higher pitch, so that when a telephone message was received from Mahukona Thursday afternoon that the Hawaii had reached that port, Hilo was in a perfect whirlwind.”

“From Puna, Puneo, Wainaku, Papaikou, from Onamea and other small places near Hilo, there was a steady inpouring of natives, dressed in either white or black.”

“Between 7 and 8 o’clock Friday morning, minute bells from Hilo Church announced that the Hawaii had come in sight, and a little later your reporter saw her drop anchor in Hilo bay, somewhat further toward the Puna side than usual.”

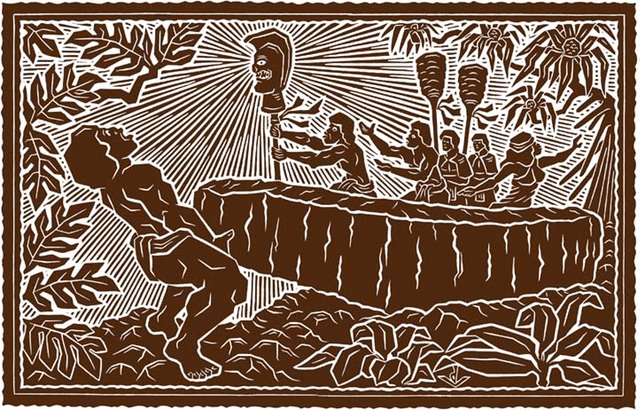

“As the Hawaii gave one long whistle, there appeared moving slowly out from Wailoa river four large double canoes manned by sturdy natives. Between each of the two were platforms for the coffin and the people who accompanied the body.”

“The head canoe was manned by natives grown old in the art of canoeing, and the top of the platform was covered with a heavy black pall.”

“As the procession of these four canoes, each with a Hawaiian flag at half mast, approached closer and closer to the steamer, the decks of the latter seemed to be all animation, and in a short time preparations were completed for putting the body off.”

“Just as the funeral canoe had reached the side and as the body was being lifted over, the steamer Hawaii, hitherto pointing directly toward Hilo, swerved around slowly and pointed to ward Waiakea, this, although being due to natural causes, striking the natives as something in the realm of the supernatural.”

“As soon as the body had been taken aboard, one lone bomb boomed out from the direction of Waiakea, and the canoe and procession of boats started away from the side of the vessel, the Hawaii swerving still further around and pointing toward Puna.”

“Long before the procession reached Waiakea, the beach near by, the jutting rocks, the bridge and every position of vantage was occupied by people, the greatest number of whom were natives.”

“The rays of the morning sun shone brightly upon the procession and upon the funeral canoe, whither all eyes were directed.”

“The appearance of this catamaran around the turn was the signal for a burst of wailing on the part of the native women, something that has never failed to strike the hearts of foreigners with a feeling of awe.”

“In a short time the funeral canoe had reached the Hilo side of Wailoa river, and the natives who had guided the corpse of Nawahi to land now stepped into the shallow water to complete their mission by lifting it off the platform and placing it upon the open funeral carriage that had been provided by the natives of Waiakea.”

“In the wagonette immediately behind the funeral carriage were Mrs. Joseph Nawahi, widow of the deceased, with Rev. Stephen L. Desha at her side, Albert and Alexander Nawahi, her two sons, Miss E. K. Nawahi, an adopted niece; Miss Simeona, another niece; Mrs. Aoe Like. Miss Anna. Mrs. Alapai and joe Kaiana.”

“When the remains had been set in Haili Church in front of the pulpit, watchers were assigned, and then came a steady inpouring of visitors to pay their last respects and bringing with them floral offerings to show their aloha for Nawahi.”

“Two o’clock Sunday afternoon found Haili Church crowded to the doors with people present to hear the services previous to burial. The front part of the old native church was a mass of flowers, in the right hand corner was a great bunch of greens of various kinds across the center of which was pinned the word ‘Aloha,’ done in marigolds.”

“Then came the sermon of Rev SL Desha in Hawaiian, abounding in richness of language and aptness of illustration, that held the attention of the audience closely. Then came the funeral procession to the graveyard, in which nearly a thousand people took part.”

“The services at the grave in the [Homelani] cemetery were very simple, and in very short time the remains of Joseph Nawahi were laid to rest in the ground and covered with the loving floral tributes of his many friends.”

“Even after the Hawaiian patriot’s death, the political struggle against annexation only intensified. The women’s chapter of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina, founded by his wife Emma Nāwahī, circulated the Kūʻē Petitions across the islands and held numerous rallies and meetings in support of their cause.”

“One of these meetings was held at the Salvation Army hall in Hilo, one week after the Republic of Hawaiʻi ratified a treaty of annexation with the United States. … Emma Nāwahī addressed the crowd of over 300 people, saying in part:”

“‘[W]e Hawaiians… have no power unless we stand together. The United States is just; a land of liberty. The people there are the friends, the great friends of the weak.’”

“‘Let us tell them—let us show them that as they love their country and would suffer much before giving it up, so do we love our country, our Hawaiʻi, and pray that they do not take it from us… In this petition, which we offer for your signature today, you, women of Hawaiʻi, have a chance to speak your mind.’”

“An account of the meeting, along with an accompanying picture, was published in the San Francisco Call (coincidentally, the same city where Joseph passed away). During a time of political turbulence matched only by Kamehameha’s unification of the archipelago, Hilo once again proved itself to be a place of powerful political action (San Francisco Call, 1897).” (HHF Story Map)