No, it’s not a typo (I don’t mean black Aces and Eights, Wild Bill Hickock’s “dead man’s hand”;) this relates to Noah Webster, Henry ʻŌpūkahaʻia, and Hawaiian grammar and spelling.

How in the world are these in common? … Let’s look.

Noah Webster (1758-1843) was the man of words in early 19th-century America. He compiled a dictionary which became the standard for American English; he also compiled The American Spelling Book, which was the basic textbook for young readers in early 19th-century America.

ʻŌpūkahaʻia, in 1809, boarded a sailing ship anchored in Kealakekua Bay and sailed to the continent. ʻŌpūkahaʻia latched upon the Christian religion, converted to Christianity in 1815 and studied at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut (founded in 1817) – he wanted to become a missionary and teach the Christian faith to people back home in Hawaiʻi.

A story of his life was written (“Memoirs of Henry Obookiah” (the spelling of his name prior to establishment of the formal Hawaiian alphabet, based on its sound.)) This book was put together by Edwin Dwight (after ʻŌpūkahaʻia died.) It was an edited collection of ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s letters and journals/diaries.

This book inspired the New England missionaries to volunteer to carry his message to the Sandwich Islands.

On October 23, 1819, the pioneer Company of missionaries from the northeast United States, set sail on the Thaddeus for the Sandwich Islands (now known as Hawai‘i) – they first landed at Kailua-Kona on April 4, 1820. (Unfortunately, ʻŌpūkahaʻia died suddenly (of typhus fever on February 17, 1818) and never made it back to Hawaiʻi.)

OK, so what about the 3s and 8s – and Hawaiian grammar and spelling?

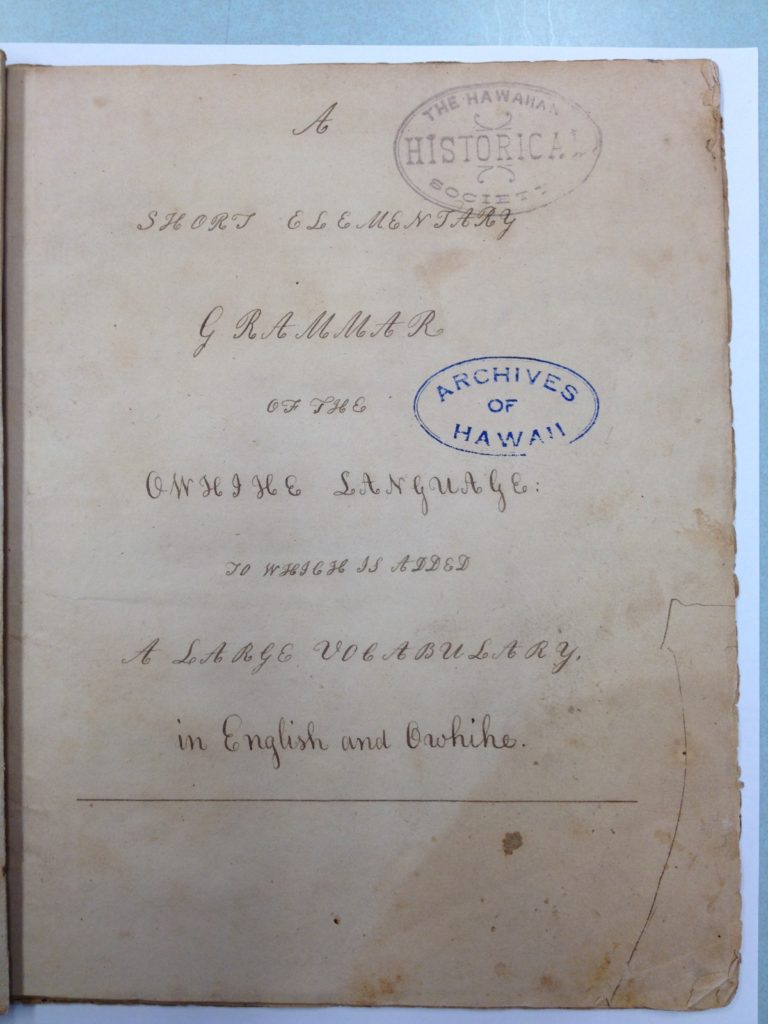

It turns out that a manuscript was found among Queen Emma’s private papers (titled, “A Short Elementary Grammar of the Owhihe Language;”) a note written on the manuscript said, “Believed to be Obookiah’s grammar”.

Some believe this manuscript is the first grammar book on the Hawaiian language. However, when reading the document, many of the words are not recognizable. Here’s a sampling of a few of the words: 3-o-le; k3-n3-k3; l8-n3 and; 8-8-k8.

No these aren’t typos, either. … Let’s look a little closer.

In his journal, ʻŌpūkahaʻia first mentions grammar in his account of the summer of 1813: “A part of the time [I] was trying to translate a few verses of the Scriptures into my own language, and in making a kind of spelling-book, taking the English alphabet and giving different names and different sounds. I spent time in making a kind of spelling-book, dictionary, grammar.” (Schutz)

So, where does Noah Webster fit into this picture?

As initially noted, Webster’s works were the standard for American English. References to his “Spelling” book appear in the accounts by folks at the New England mission school.

As you know, English letters have different sounds for the same letter. For instance, the letter “a” has a different sound when used in words like: late, hall and father.

Noah Webster devised a method to help differentiate between the sounds and assigned numbers to various letter sounds – and used these in his Speller. (Webster did not substitute the numbers corresponding to a letter’s sound into words in his spelling or dictionary book; it was used as an explanation of the difference in the sounds of letters.)

The following is a chart for some of the letters related to the numbers assigned, depending on the sound they represent.

Long Vowels in English (Webster)

..1……..2…….3………4……….5…….6………7……….8

..a……..a…….a………e……….i……..o………o……….u

late, ask, hall, here, sight, note, move, truth

Using ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s odd-looking words mentioned above, we can decipher what they represent by substituting the code and pronounce the words accordingly (for the “3,” substitute with “a”(that sounds like “hall”) and replace the “8” with “u,” (that sounds like “truth”) – so, 3-o-le transforms to ʻaʻole (no;) k3-n3-k3 transforms to kanaka (man;); l8-n3 transforms to luna (upper) and 8-8-k8 transforms to ʻuʻuku (small.)

It seems Henry ʻŌpūkahaʻia used Webster’s Speller in his writings and substituted the numbers assigned to the various sounds and incorporated them into the words of his grammar book (essentially putting the corresponding number into the spelling of the word.)

“Once we know how the vowel letters and numbers were used, ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s short grammar becomes more than just a curiosity; it is a serious work that is probably the first example of the Hawaiian language recorded in a systematic way. Its alphabet is a good deal more consistent than those used by any of the explorers who attempted to record Hawaiian words.” (Schutz)

“It might be said that the first formal writing system for the Hawaiian language, meaning alphabet, spelling rules and grammar, was created in Connecticut by a Hawaiian named Henry ʻŌpūkahaʻia. He began work as early as 1814 and left much unfinished at his death in 1818.” (Rumford)

“His work served as the basis for the foreign language materials prepared by American and Hawaiian students at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut, in the months prior to the departure of the first company of missionaries to Hawai’i in October 1819.” (Rumford)

It is believed ʻŌpūkahaʻia classmates (and future missionaries,) Samuel Ruggles and James Ely, after ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s death, went over his papers and began to prepare material on the Hawaiian language to be taken to Hawaiʻi and used in missionary work (the work was written by Ruggles and assembled into a book – by Herman Daggett, principal of the Foreign Mission School – and credit for the work goes to ʻŌpūkahaʻia.)

Lots of information here from Rumford (Hawaiian Historical Society) and Schutz (Honolulu and The Voices of Eden: A History of Hawaiian Language Studies.)

I encourage you to review the images in the folder; I had the opportunity to review and photograph the several pages of ʻŌpūkahaʻia’s grammar book.