In modern land description, the context is ‘spatial’ – we tend to reference things by their location, area and use – 123 Main Street, 10,000-square feet, residential.

Look at any map, GPS orientation or recall how you describe a place, etc, it’s all about space and location; you learn where you are and the physical context of it.

In old Hawaiʻi, it was the nature of ‘place’ that shaped the practical, cultural and spiritual view of the Hawaiian people.

In Hawaiian culture, natural and cultural resources are one and the same. Traditions describe the formation (literally the birth) of the Hawaiian Islands and the presence of life on, and around them, in the context of genealogical accounts.

All forms of the natural environment, from the skies and mountain peaks, to the watered valleys and lava plains, and to the shore line and ocean depths are believed to be embodiments of Hawaiian gods and deities. (Maly)

“The ancients gave names to the natural features of the land according to their ideas of fitness. … There were many names used by the ancients to designate appropriately the varieties of rain peculiar to each part of the island coast; the people of each region naming the varieties of rain as they deemed fitting. … The ancients also had names for the different winds.” (Malo)

Hawaiians named taro patches, rocks, trees, canoe landings, resting places in the forests and the tiniest spots where miraculous events are believed to have taken place. (hawaii-edu) There were names for everything, and multiple names for many.

Place names are often descriptive of: (1) the terrain, (2) an event in history, (3) the kind of resources a particular place was noted for or (4) the kind of land use which occurred in the area so named. Sometimes an earlier resident of a given land area was also commemorated by place names. (Maly)

“Cultural Attachment” embodies the tangible and intangible values of a culture – how a people identify with, and personify the environment around them.

It is the intimate relationship (developed over generations of experiences) that people of a particular culture feel for the sites, features, phenomena and natural resources etc, that surround them – their sense of place. This attachment is deeply rooted in the beliefs, practices, cultural evolution and identity of a people. (Kent)

In ancient Hawai‘i, most of the common people were farmers, a few were fishermen. Access to resources was tied to residency and earned as a result of taking responsibility to steward the environment and supply the needs of aliʻi. Tenants cultivated smaller crops for family consumption, to supply the needs of chiefs and provide tributes.

In this subsistence society, the family farming scale was far different from commercial-purpose agriculture. In ancient time, when families farmed for themselves, they adapted; products were produced based on need. The families were disbursed around the Islands. An orderly delineation became needed.

Māʻilikūkahi is noted for clearly marking and reorganizing land division palena (boundaries) on O‘ahu. Defined palena brought greater productivity to the lands; lessened conflict and was a means of settling disputes of future aliʻi who would be in control of the bounded lands; protected the commoners from the chiefs; and brought (for the most part) peace and prosperity. (Beamer, Duarte)

Fornander writes, “He caused the island to be thoroughly surveyed, and boundaries between differing divisions and lands be definitely and permanently marked out, thus obviating future disputes between neighboring chiefs and landholders.”

Kamakau tells a similar story, “When the kingdom passed to Māʻilikūkahi, the land divisions were in a state of confusion; the ahupuaʻa, the ku, the ʻili ʻāina, the moʻo ʻāina, the pauku ʻāina, and the kihāpai were not clearly defined.”

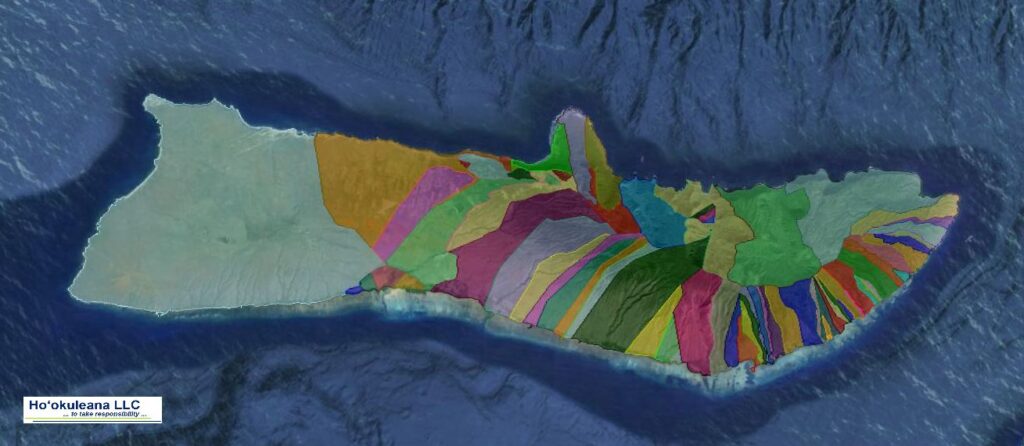

“Therefore, Māʻilikūkahi ordered the chiefs, aliʻi, the lesser chiefs, kaukau aliʻi, the warrior chiefs, puʻali aliʻi, and the overseers (luna) to divide all of Oʻahu into moku, ahupuaʻa, ʻili kupono, ʻili ʻaina, and moʻo ʻāina.”

What is commonly referred to as the “ahupuaʻa system” is a result of the firm establishment of palena (boundaries.) This system of land divisions and boundaries enabled a konohiki (land/resource manager) to know the limits and productivity of the resources that he managed.

Ahupuaʻa served as a means of managing people and taking care of the people who support them, as well as an easy form of collection of tributes by the chiefs. Ultimately, this helped in preserving resources.

A typical ahupuaʻa (what we generally refer to as watersheds, today) was a long strip of land, narrow at its mountain summit top and becoming wider as it ran down a valley into the sea to the outer edge of the reef. If there was no reef then the sea boundary would be about one and a half miles from the shore.

When the Hawaiians lived on the land as farmers and gatherers they became intimately acquainted with and named countless features and places.

Hawaiian customs and practices demonstrate the belief that all portions of the land and environment are related; the place names given to them tell us that areas are of cultural importance. (Maly)

This Placial versus Spatial context reflects the relationship of the people to the land.

“Sense of place is about the feeling that emanates from a place as a combination of the physical environment and the social construct of people activity (or absence of) that produces the feeling of a place. … People seek out Hawaiʻi because of the expectation of what its sense of place will be when they get there.” (Apo)

“Sense of place helps to define the relationships we have as hosts and guests, as well as how we treat one another and our surroundings.” (Taum)

“In the Hawaiian mind, a sense-of-place was inseparably linked with self-identity and self-esteem. To have roots in a place meant to have roots in the soil of permanence and continuity.”

“Almost every significant activity of his life was fixed to a place.”

“No genealogical chant was possible without the mention of personal geography; no myth could be conceived without reference to a place of some kind; no family could have any standing in the community unless it had a place; no place of significance, even the smallest, went without a name; and no history could have been made or preserved without reference, directly or indirectly, to a place.”

“So, place had enormous meaning for Hawaiians of old.” (Kanahele)