A century after Captain James Cook’s arrival in Hawaiʻi, sugar plantations started to dominate the Hawai‘i landscape. Hawai‘i’s economy turned toward sugar in the decades between 1860 and 1880; these twenty years were pivotal in building the plantation system.

However, a shortage of laborers to work in the growing (in number and size) sugar plantations became a challenge. The only answer was imported labor.

Starting in the 1850s, when the Hawaiian Legislature passed ‘An Act for the Governance of Masters and Servants,’ a section of which provided the legal basis for contract-labor system, labor shortages were eased by bringing in contract workers from Asia, Europe and North America.

There were three big waves of workforce immigration: Chinese 1852; Japanese 1885; and Filipinos 1905. Several smaller, but substantial, migrations also occurred: Portuguese 1877; Norwegians 1880; Germans 1881; Puerto Ricans 1900; Koreans 1902 and Spanish 1907.

In March 1881, King Kalākaua visited Japan during which he discussed with Emperor Meiji Hawaiʻi’s desire to encourage Japanese nationals to settle in Hawaiʻi.

Kalākaua’s meeting with Emperor Meiji improved the relationship of the Hawaiian Kingdom with the Japanese government and an economic depression in Japan served as motivation for Japanese agricultural workers to move from their homeland. (Nordyke/Matsumoto)

The first 943-government-sponsored, Kanyaku Imin, Japanese immigrants to Hawaiʻi arrived in Honolulu on February 8, 1885. Subsequent government approval was given for a second set of 930-immigrants who arrived in Hawaii on June 17, 1885.

With the Japanese government satisfied with treatment of the immigrants, a formal immigration treaty was concluded between Hawaiʻi and Japan on January 28, 1886. The treaty stipulated that the Hawaiʻi government would be held responsible for employers’ treatment of Japanese immigrants.

The Issei (first generation) were born in Japan and emigrated to Hawai‘i from 1885 to 1924 (when Congress stopped all legal migration.) (The Immigration Act of 1924 (aka Johnson-Reed Act) limited the number of immigrants allowed entry into the US through a national origins quota. It completely excluded immigrants from Asia. (State Department))

The sugar industry came to maturity by the turn of the century; the industry peaked in the 1930s. Hawaiʻi’s sugar plantations employed more than 50,000 workers and produced more than 1-million tons of sugar a year; over 254,500-acres were planted in sugar.

Like the other ethnic immigrant groups, the Issei worked on sugar and pineapple plantations. The children of the Issei were the Nisei, the second generation in Hawaiʻi. They are the first generation of Japanese descent to be born and receive their entire education in America, learning Western values and holding US citizenship.

Over time, many Issei and Nisei moved to Honolulu and other developing urban centers. The alien land laws encouraged urbanization since non-citizens could not own land. Many of the Issei became independent wage earners, merchants, shopkeepers, and tradesmen. They sought and began to achieve upward mobility. (Nordyke and Matsumoto)

On July 7, 1937, Japan invaded China to initiate the war in the Pacific; while the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, unleashed the European war.

If the US and Japan went to war, Japanese in Hawai‘i were seen as potentially dangerous. Both the Army and the FBI gathered data on Japanese residents in the late-1930s.

Fingerprinting and registering of aliens began in August of 1940 under provisions of the federal Alien Registration Act; some 6,000 aliens in Hilo alone were registered and fingerprinted beginning in September of 1940. (Farrell)

During the Fall of 1941 diplomatic relations between the US and Japan, which had been steadily deteriorating, took a sudden turn for the worse.

As to Hawaiʻi, War Department message of November 27, 1941 read as follows: “Negotiations have come to a standstill at this time. No diplomatic breaking of relations and we will let them make the first overt act. You will take such precautions as you deem necessary to carry out the Rainbow plan [a war plan]. Do not excite the civilian population.” (Proceedings of Army Pearl Harbor Board)

An FBI memo, dated December 4, 1941, referenced the “custodial detention list,” a listing of people who should be arrested in the event of outbreak of war. (Farrell)

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the US at Pearl Harbor. At that time, Hawaii’s Japanese population was about 158,000, more than one-third of the territory’s total population. (Cohen)

Less than 4 hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, territorial governor Joseph B Poindexter invoked the Hawaii Defense Act giving him absolute wartime power in Hawai‘i.

By mid-afternoon (3:30 pm) the decision to place the territory under martial law was made, suspending the writ of habeas corpus and placing control of Hawaiʻi under Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, who became Military Governor.

The War Department, working under the authority of martial law, ordered that everyone on the list be interned. (Moniz Nakamura)

Kilauea Military Camp (KMC) at Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park (then known as Hawaii National Park) had been a quiet military recreation facility. By the end of the day on December 7th, it became a detainment camp.

For the island of Hawai‘i, the FBI’s detention list included a total of 82 individuals: 67 consular agents, 3 priests, and 12 “others” (business leaders and other important people in the Japanese American community). (Farrell)

The local police, with assistance from the FBI and Army Intelligence, immediately rounded up and detained the “suspicious aliens” – most of them prominent figures in the Japanese community. (Chapman)

Traveling under police custody in several cars, they passed the Hilo entrance of the park and proceeded to KMC where they were held under military guard in the small camp stockade and in nearby barracks. Within a few days, others had joined this group, which eventually expanded to approximately 130 men.

The detainees included prominent Japanese residents from Hilo and outlying planation areas, many of them familiar to both military and NPS personnel. Many were teachers; others were prominent business or community figures. (Chapman)

“At Kilauea, internees had to walk among soldiers armed with bayonets. While food was plentiful and nutritious, the dignity of the people was taken away. Internees were constantly accompanied by soldiers – even to the latrine”.

At mealtime, inmates lined up to go to the mess hall, which was across the open ground from their barracks, between ten guards with guns and fixed bayonets (Hoshida; Farrell)

In the mess hall, prisoners were initially surprised by the bounty of food that was available to them and as detainee Myoshu Sasai reported, “we could eat all that we wanted to. If they ran out of something, all we had to do was to raise our hand.”

A long serving counter separated the kitchen from the mess hall. Inmates picked up stainless serving trays and silverware and walked single file in front of the serving tables while waiting for kitchen personnel to serve them food, then sat six to wooden tables and benches. (Nakamura; Densho)

A sense of camaraderie developed among the inmates as noted by inmate Yoshio “George” Hoshida who observed that “here, sharing together the same fate in this time of emergency, they were brought together closer as humans on equal plane and closer comradeship.” (Nakamura; Densho)

For one hour every day, detainees were allowed outside for exercise. Inmates also occupied their days reading magazines and books, walking around, or writing letters. For many, letter writing was the only way of communicating with their families and maintaining personal ties.

Although letters were censored with officials cutting out any account of the camp, Hoshida recalled that “letter writing became the main consolation and receiving them was a source of great pleasure to be looked forward to each day.” (Nakamura; Densho)

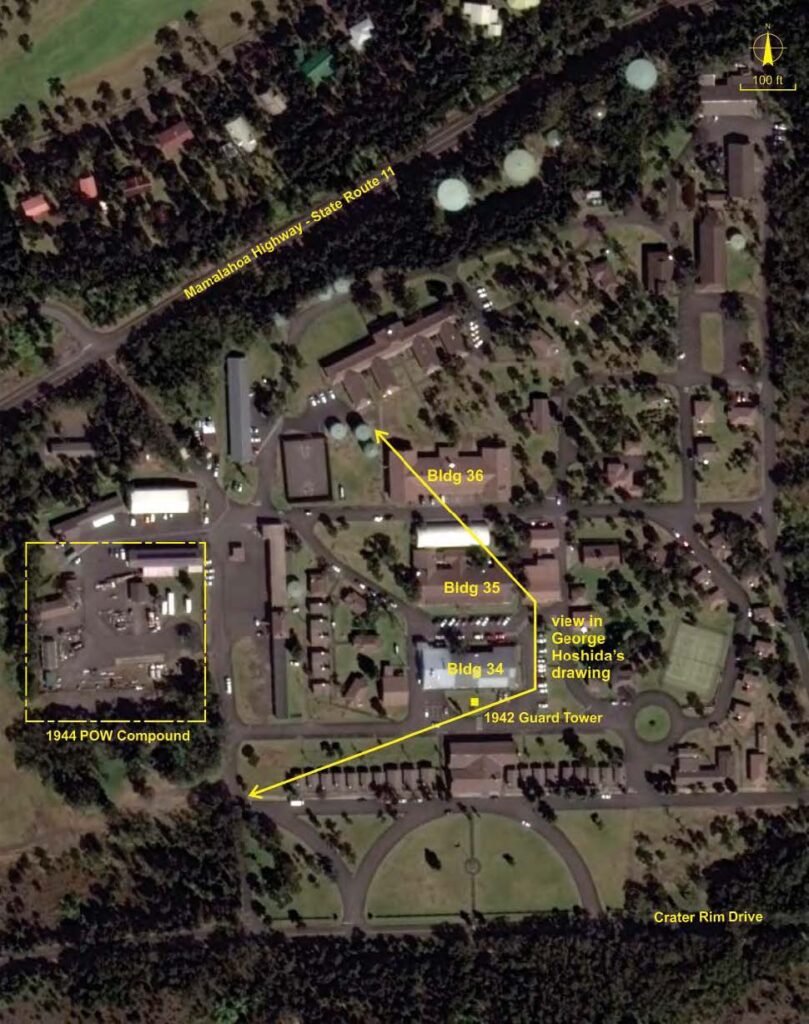

Building 34, now the Crater Rim Café, Lava Lounge and post office, was used as the internee barracks. Building 35, now the recreation center, was built as an enlisted men’s mess hall and converted to a dormitory in 1919. It was used as the internee mess hall in 1943, but became the recreation hall in 1945. (Farrell)

Internee hearings were held in the Federal Building on Waianuenue Avenue in downtown Hilo. Because the hearings lasted several days, it is probable that internees were held overnight at the Old Police Station, on Kalākaua Street and directly across Kalākaua Park from the Federal Building. (Farrell)

By mid-February 1942, the military government determined that under the Geneva Convention interned aliens could not be held in a combat zone.

On February 15, authorities announced that immediate family members could visit. In anticipation of an imminent transfer to another facility, families were advised to bring warm clothes and that each internee could possess $50.

Noting that the internees were not prisoners of war, the authorities soon began the process of relocation to Sand Island or eventual transfer to the continental United States. The first group of 106 internees departed Kīlauea on March 6; the last group of 25 left on May 12. (Chapman)

In all, between 1,200 and 1,400 local Japanese in Hawai’i were interned, along with about 1,000 family members. By contrast, Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized the mass exclusion and detention of all Japanese Americans living in the West Coast states, resulting in the eventual incarceration of 120,000 people.

The detainees were never formally charged and granted only token hearings. Many of the detainees’ sons served with distinction in the US armed forces, including the legendary 100th Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team and Military Intelligence Service.

Following the departure of Japanese inmates in 1942, in June 1944, an addition to KMC was built on the west side, in the area that is now the motor pool. These facilities would serve as a prisoner of war (POW) camp for Koreans and Okinawans who had been brought to the US from islands captured from the Japanese. (Moniz Nakamura)

Military authorities assigned the POWs to maintenance work around the camp. The prisoners generally worked without supervision, mostly on landscape projects and other maintenance work. (Chapman)

The current chain link fence around Tours & Transportation (Bldg 84), Housekeeping (Bldg 81) and Fire & Paramedic Services (Bldg 59) follows the same footprint as the outer wire of the POW camp enclosure. (KMC Walking Tour Narrative)

I’m sure my relatives were interned here while my side was interned at Tule Lake. Still hard to believe this happened in America.