In Mangaian, the pua tree was the tree that guarded the entrance to the land of the spirits in the underworld (Mangaia, traditionally known as Aʻuaʻu Enua (which means terraced) is the most southerly of the Cook Islands.) (Neal, Agroforestry)

In Tahitian legend, the first pua tree was brought from the tenth heaven by Tane, god of the forests. Hence the tree is sacred to him, and the images of him were always made of pua wood. (Neal, Agroforestry)

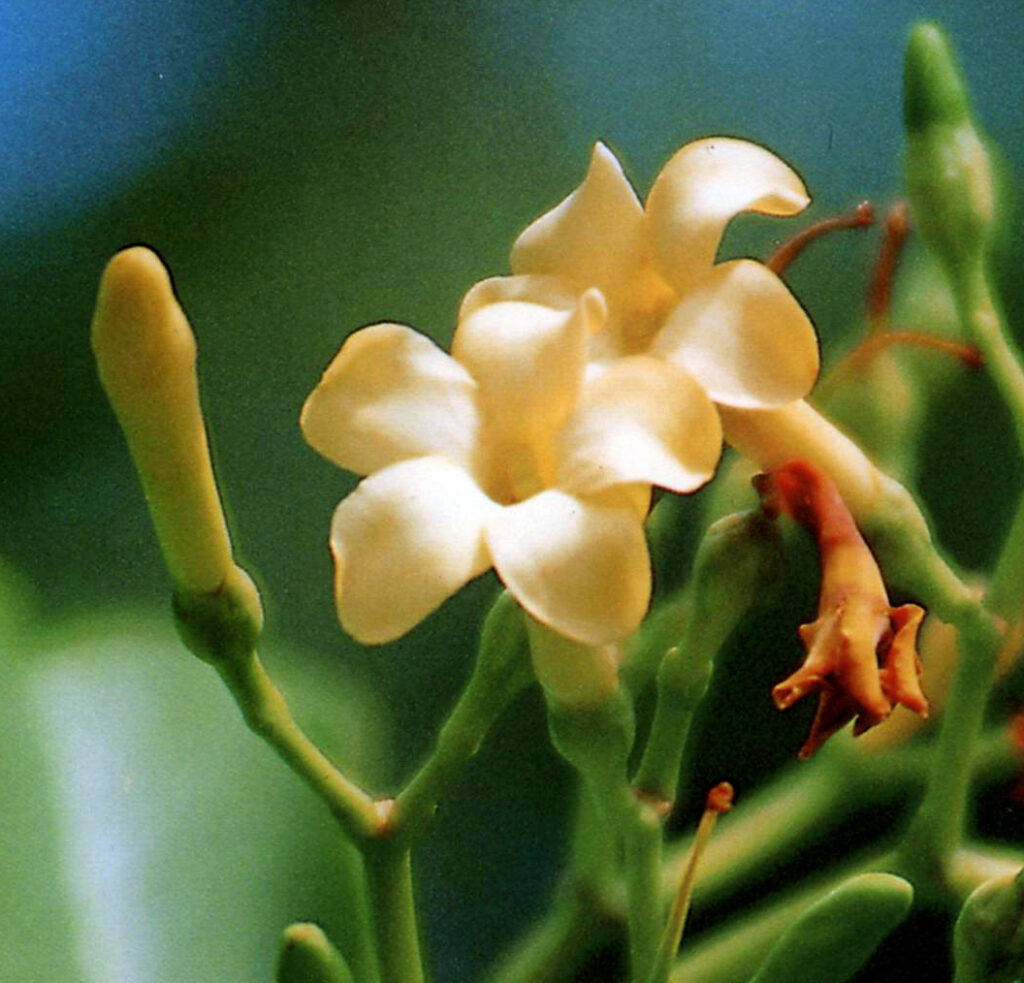

Indigenous from New Guinea and Northern Australia, to the Marianas and eastward to the Caroline Islands (east of the Marquesas,) it is a shrub or small tree (Fagraea berteriana) grown ornamentally for foliage, flowers and fruit.

Its original Polynesian name was simply “pua” which is still used over most of its native range in Polynesia and is a cognate of the Fijian name. The tree was considered sacred in the Cooks and Tahiti in ancient times. Concoction of the inner bark was used in treating asthma and diabetes. (Whistler)

It is grown in most Polynesian countries like Tonga, Niue, Uvea, Societies, Cooks, Australs, Mangareva, Marquesas, Samoa (pua lulu.)

In Hawaiʻi, it is called puakenikeni.

Approximately 9,000 new species of flowering plants were introduced to Hawaiʻi from all over the world during the over two centuries since ‘Contact’ (1778.)

Some, including puakenikeni (as well as plumeria, carnation, ginger, pīkake, pakalana and pua male (Stephanotis,)) quickly became favorites of island residents and staples of the lei industry. (CTAHR)

Lei makers down on the Honolulu docks selling lei during the “Steamer Days” or “Boat Days” (late-1800s to mid-1900s) would string the puakenikeni into fragrant lei.

It earned its name Pua Kenikeni (Puakenikeni) here in Hawaiʻi because at one time the flowers were sold for making lei, each flower (“pua”) cost a dime (kenikeni means dime, ten cents,) hence the name “ten-cent flower.” (Pukui, Neal, Agroforestry)

“500 persons in Honolulu make a living wholly or partly by selling leis – those fragrant garlands of pikake, ginger blossoms, gardenias, tube roses, carnations and a score of other flowers – which are dangled about the neck upon any excuse from a sailing to a dinner table.” (The Sunday Morning, June 6, 1937)

Flowers are best harvested 2-3 times per week in early morning. Open white flowers can be stored at room temperature for up to 3-days.

While most lei do well in dry plastic bags kept in the refrigerator, the exception is puakenikeni which turns brown if refrigerated. Instead, keep it between damp paper towels in a flat container set in a cool, dark place.

It is one of the few flowers that has three different colors as it ages (with the same scent throughout.) The first day it’s creamy white, by the second it’s at buttery yellow and on the third it’s a creamy orange.

Lei Pua Kenikeni – Written by John Kameaaloha Almeida (1897-1985)

(Translated by Mary Pukui)

(Click HERE for rendition of Puakenikeni performed by Mark Yamanaka)

No ka lei aloha, lei pua kenikeni

Koʻu hiaʻai a me koʻu hoʻohihi

Ke ʻala hoʻoheno kaʻu aloha

I ka ne mai e welilna kaua

Kaua i ka nani a o ia pua

I ka hana hoʻoipo a ke onaona

Onaona lei nani lei hoʻohie

Hoʻoipo, hoʻoulu mahiehie

Mapu ʻala hoʻoheno i ka poli

Lanikeha i ka ike a ka maka

Eia no ka puana o ke mele

No ka lei pua kenikeni he inoa

For the beloved lei of pua kenikeni

My admiration and delight

Its pleasing perfume I enjoy

Which tells our love for each other

May you and I admire the flowerʻs beauty

With its subtle fragrance so appealing

Fragrant, beautiful and excellent is the lei

Appealing and most attractive

Its soft perfume wins the heart

Its beauty is most entrancing

This is the ending of this song

In praise of the pua kenikeni