Volcanoes … yes. But that is not what this story is about.

These are some of the names of inter-island steam ships that operated between the Islands; and in the day, they were the only way to get from here to there, when you travelled inter-island.

Competitors Wilder Steamship Co (1872) and Inter-Island Steam Navigation Co (1883) ran different routes, rather than engage in head to head competition.

Inter-Island operated the Kauaʻi and Oʻahu ports plus some on Hawaiʻi. Wilder took Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi and Maui plus Hawaiʻi ports not served by Inter-Island. Both companies stopped at Lāhainā, Māʻalaea Bay and Makena on Maui’s leeward coast. (HawaiianStamps)

Mahukona, Kawaihae and Hilo were the Big Island’s major ports; Inter-Island served Kona ports, Kaʻū ports and the Hāmākua ports of Kukuihaele, Honokaʻa and Kūkaʻiau. Wilder served Hilo and the Hāmākua stops at Paʻauhau, Paʻauilo and Laupāhoehoe.

For Inter-Island’s routes, vessels left Honolulu stopping at Lāhainā and Māʻalaea Bay on Maui and then proceeding directly to Kailua-Kona.

From Kailua, the steamer went south stopping at the Kona ports of Nāpoʻopoʻo on Kealakekua Bay, Hoʻokena, Hoʻopuloa, rounding South Point, touching at the Kaʻū port of Honuʻapo and finally arriving at Punaluʻu, Kaʻū, the terminus of the route. (From Punaluʻu, five mile railroad took passengers to Pahala and then coaches hauled the visitors to the volcano from the Kaʻū side.)

Wilder’s steamers left Honolulu and stopped at the Maui ports of Lāhainā, Māʻalaea Bay and Makena and then proceeded to Mahukona and Kawaihae. From Kawaihae, the steamers turned north, passing Mahukona and rounding Upolu Point at the north end of Hawaiʻi and running for Hilo along the Kohala and Hāmākua coasts, stopping at Laupāhoehoe. (Visitors for Kilauea Crater took coaches from Hilo through Olaʻa to the volcano.)

Later, inter-island trade was carried almost exclusively by the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Co, the successor to the firm of Thomas R Foster & Co (the original founders of the company) and which, in 1905, acquired the Wilder Steamship Co. (Congressional Record)

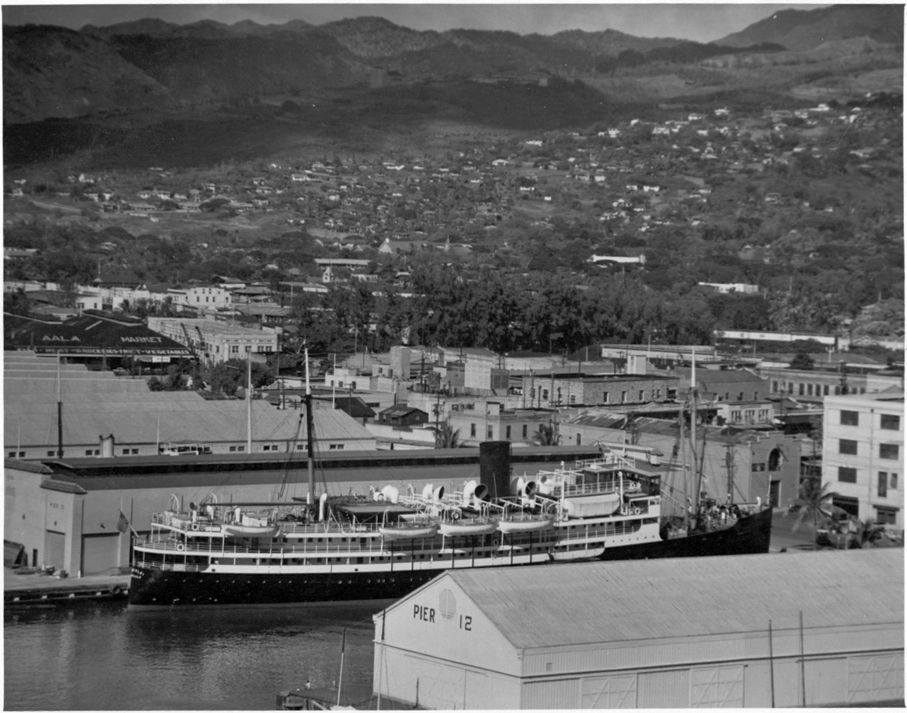

“The Inter-Island Steam Navigation Co, established in 1883, own(ed) and operate(d) a fleet of first-class vessels engaged exclusively in the transportation of passengers and freight between ports on the islands of the Hawaiian group.” (Annual Report of the Governor, 1939)

Regular sailings of passenger vessels are maintained from Honolulu four times weekly to ports on the island of Hawaiʻi, four times weekly to Molokaʻi, twice weekly to Kauaʻi, three times weekly to Lānaʻi and daily, except Monday and Saturday, to ports on the island of Maui. Included in the fleet are 12 passenger and freight vessels.” (Report of the Governor, 1930)

During the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, Inter-Island Steam Navigation had the SS Haleakalā, Hualālai, Kilauea and Waiʻaleʻale. There were others that carried 12-passengers such as the SS Humuʻula, which was primarily a cattle boat.

Haleakalā, a steel screw steamer, was built by Sun Ship, Chester, PA in 1923 for the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company. She first arrived at Honolulu March 15, 1923 and put on the Hilo route with accommodations for 261 cabin and 90 deck passengers.

She was later laid up as a reserve vessel when the Hualālai was put into service; resold and renamed several times, Haleakala was sold for scrap and demolished February 2, 1955.

Hualālai, a twin-screw steel steamer, was built at Bethlehem Shipbuilding, San Francisco, CA in 1929. After inter-island use, she was later, sold, resold and renamed a couple of times, and later scrapped in May 1960.

Waiʻaleʻale, another passenger ship, was a twin-screw steel steamer put into service by the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company in June 1928. After the war, she was put under the Philippine flag, later returned to Honolulu in 1948 and scrapped in September 1954.

Others included Kilauea, put into passenger and freight service in 1911, Hawaiʻi in October 1924 and Humuʻula in 1929.

Once aboard, the purser collected the $5 fare. Of course, cabins were available, but more expensive at $10. Most passengers selected steerage, which was the lowest fare. (Rodenhurst)

The steerage area was a large open area aft, on the second deck. Wooden slats covered the steel deck. People would stake out their space with mats and luggage, then settle down to eat their food. (Rodenhurst)

“Twice a week the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company dispatches its palatial steamers, “Waiʻaleʻale” and “Hualālai,” to Hilo, leaving Honolulu at 4 pm on Tuesdays and Fridays, arriving at Hilo at 8 am the next morning. From Honolulu, the Inter-Island Company dispatches almost daily excellent passenger vessels to the island of Maui and twice a week to the island of Kauaʻi.” (The Mid-Pacific, December 1933)

“There is no finer cruise in all the world than a visit to all of the Hawaiian Islands on the steamers of the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company. The head offices in Honolulu are on Fort at Merchant Street, where every information is available, or books on the different islands are sent on request.”

“Tours of all the islands are arranged. Connected with the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company is the world-famous Volcano House overlooking the everlasting house of fire, as the crater of Halemaʻumaʻu is justly named. A night’s ride from Honolulu and an hour by automobile and you are at the Volcano House in the Hawaii National Park on the Island of Hawaiʻi, the only truly historic caravansary of the Hawaiian Islands.” (The Mid-Pacific, December 1933)

“Many steamers each week call at ports of Hawaiʻi from Honolulu. The Inter-Island company has a fine steamer on this run for tourists, and (added) a steamer with a capacity of 350 passengers, large and commodious as any ocean liner, to carry passengers on the ‘Volcano run,’ making two trips a week.” (Taylor)

When James A Kennedy joined Inter-Island in 1900 it was in an early stage of its development, and it had become a corporation when he retired from the presidency and general managership in 1924. He remained a member of the board of directors.

In 1928, his son, Stanley C Kennedy, a Silver Star Navy pilot, convinced the board of directors of Inter-Island Steam Navigation of the importance of air service to the Territory and formed Inter-Island Airways.

Young Kennedy had visions of flying for many years. But it was not until the Great War that Stanley Kennedy was to pilot an airplane. Dissatisfied with a Washington desk job, the naval officer talked his way into flight training in Pensacola, Florida. In short order, Ensign Kennedy sported wings as Naval Aviator No. 302. (hawaii-gov)

On November 11, 1929, Inter-Island Airways, Ltd introduced the first scheduled air service in Hawaiʻi with a fleet of two 8-passenger Sikorsky S-38 amphibian airplanes. The first flight from Honolulu to Hilo with stops on Molokaʻi and Maui took three hours, 15 minutes. (It was later renamed Hawaiian Airline.) (hawaii-gov)

Eventually, in 1950, the inter-island ships were sold and the business closed down as air travel took over. “It was sad to have another part of Hawaiʻi’s past fade into history. Nevertheless, these once-in-a-lifetime experiences will remain in my memory forever.” (Rodenhurst)