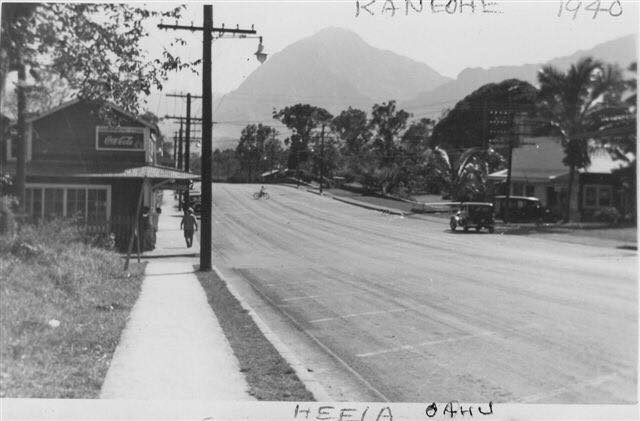

The nine ahupuaʻa of Kāneʻohe Bay, beginning at the boundary between Koʻolauloa and Koʻolaupoko Districts (west) and moving eastward, are Kualoa, Hakipuʻu, Waikāne, Waiāhole, Kaʻalaea, Waiheʻe, Kahaluʻu, Heʻeia and Kāneʻohe.

The ahupuaʻa of Heʻeia and Kāneʻohe also included portions of Mōkapu Peninsula (Heʻeia runs from the mountains to the sea, but also crosses over a portion of the water in Kāneʻohe Bay and includes a portion of a Mōkapu peninsula across the Bay.) Heʻeia also includes Moku-o-Loʻe (Coconut Island,) Kahaluʻu includes Kapapa Island and Kualoa includes Mokoliʻi.

The name of the land of Heʻeia is traditionally associated with Heʻeia, the handsome foster son of the goddess Haumea and grandson of the demigod ʻOlopana, who was an uncle of Kamapuaʻa.

Heʻeia was named in commemoration of a tsunami-type wave that washed Haumea and others into the sea – a great tidal wave that “washed (he‘e ‘ia) … out to sea and back” (Lit., surfed, or washed (out to sea,) or swept away.)

They swam until they were exhausted and were finally washed ashore at Kapapa Island in Kāneʻohe Bay. It was the handsome Heʻeia who fell in love with Kaohelo, a younger sister of Pele and Hiʻiaka, whom he met in Koʻolau, Oʻahu. (Devaney)

In ancient Hawai‘i, fishponds were an integral part of the ahupua‘a food source. Hawaiians built rock-walled enclosures in near shore waters to raise fish for their communities and families. Loko iʻa (fishpond) were used for fattening and storing of fish for food and also as a source for kapu (forbidden) fish. Walled, brackish-water fishponds were usually constructed on the reef along the shore and one or more mākāhā (sluice gate.)

Heʻeia Fishpond’s wall was one of the longest, extending nearly a mile. As a large pond, it is subject to considerable evaporation, increasing salinity in the pond; as such, fresh water is added. Heʻeia is somewhat unique in that it has mākāhā gates on the mauka wall to control the flow of fresh water.

Kalo (taro) was a main staple in the diet of nearly all Hawaiians prior to European contact and was extensively cultivated. As early as 1789, Portlock described this area:

“… the bay all around has a very beautiful appearance, the low land and valleys being in high state of cultivation, and crowded with plantations of taro, sweet potatoes, sugar-cane, etc. interspersed with a great number of coconut trees ….”

The region had a considerable amount of land cultivated in taro up through the early-1800s. “Southeastward along the windward coast, beginning with Waikāne and continuing through Waiāhole, Kaʻalaea, Kahaluʻu, Heʻeia and Kāne’ohe, were broad valley bottoms and flatlands between the mountains and the sea which, taken all together, represent the most extensive wet-taro area on Oʻahu.” (Handy, Devaney)

The rains that sweep through here have been memorialized in poetry and song. A traditional mele honoring Kaumuali‘i suggests “the sound of heavy rain drops on dry leaves, or dry thatching of the pandanus leaf, … of the rain accompanying the koʻolau wind, which calms the troubled waters”.

This “heavy-sounding rain” of the Koʻolau has been transformed into a poetical saying, “Ka ua kani koʻo o Heʻeia, The rain of Heʻeia that sounds like the tapping of walking canes”. (Fornander)

During the early historic times, many of the ruling chiefs favored this area as their place of residence. Kahahana the ruler of Oʻahu sometimes resided there. Kahekili after defeating Kahahana lived in Kailua, Kāneʻohe and Heʻeia.

The Sacred Hearts Father’s College of Ahuimanu was founded by the Catholic mission at Ahuimanu, Heʻeia in 1846. “Outside the city, at Ahuimanu, Maigret has now a country retreat that he refers to by the Hawaiian word māla. It is a combination garden, orchard and kitchen garden. …”

“The venerable bishop has built his own vineyard and planted his own orchard … His retreat in the mountain, his “garden in the air” as he terms it, is a pleasant and profitable sight … When the pressure of events allows it, Maigret takes refuge there.” (Charlot)

One of its students, Damien (born as Jozef de Veuster,) arrived in Hawaiʻi on March 9, 1864, at the time a 24-year-old choirboy. Determined to become a priest, he had the remainder of the schooling at the College of Ahuimanu. Bishop Maigret ordained Father Damien at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Peace in 1864 and later assigned him to Molokaʻi. In 2009, Father Damien was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI.

The earliest of the modern large commercial agricultural ventures started with the cultivation of sugar cane in Kualoa in the 1860s. By 1880, three more sugar companies had emerged in Kahaluʻu, Heʻeia and Kāne’ohe. Heʻeia Sugar Company (also called Heʻeia Agricultural Co. Ltd) operated from 1878 to 1903.

In 1880, the region reported 7,000-acres available for cultivation; in 1883 a railroad was installed at Heʻeia, and by the summer of that year it was noted that the railroad had allowed a much greater amount of land to be harvested, even allowing cane from Kāneʻohe to be ground at Heʻeia; however, the commercial cultivation of sugar cane was short-lived. (Devaney)

Rice cultivation did not occur in earnest until the decline of sugar, and in 1880 the first Chinese rice company started in the nearby Waineʻe area. Abandoned systems of loʻi kalo were modified into rice paddies. The Kāneʻohe Rice Mill was built around 1892-1893 in nearby Waikalua.

Another commercial crop, pineapple, was also grown here, starting around 1910. By 1911, Libby, McNeill & Libby gained control of land here and built the first large-scale cannery with an annual capacity of 250,000-cans at nearby Kahaluʻu; growing and canning pineapples became a major industry in the area for a period of 15 years (to 1925.)

The US military first established a presence on the Mōkapu peninsula in 1918 when President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order establishing Fort Kuwaʻaohe Military Reservation (the western portion of Mōkapu is within the Heʻeia ahupuaʻa.)

Today, Marine Corps Base Hawaiʻi continues to serve as a fully functional operational and training base for US Marine Corps forces. The Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) here operates a 7,800-foot runway (on the ahupuaʻa of Heʻeia) that can accommodate both fixed wing and rotor-driven aircraft.

With World War II underway, the Navy recognized the need to be able to communicate across the Pacific. In 1942, a group of radio experts determined a superpower radio station with across-the-Pacific range might be built provided that the antenna could be raised high enough above the ground.

The solution was to find a topographic feature that would act like the “unbuildable” tall tower. Using technology developed pre-World War I, they strategically positioned four Alexanderson Alternators; one was located in Haiku Valley in Heʻeia. Haiku Valley with its horseshoe shape and sheer side-walls filled the prescription perfectly.

To build it, mountain climbers pounded spikes into the vertical cliff, then added wooden stairs up the mountain. A lift to haul up materials was added and they strung cables across the valley. The Alexanderson Alternator radio system, transmitting Morse code across the Pacific, was operational in 3-months. A reminder of that facility is the Haiku Ladder, Haiku Stairs – the Stairway to Heaven (a 3,922-step ladder/stairway ascending the summit of the Koʻolau mountain range.)

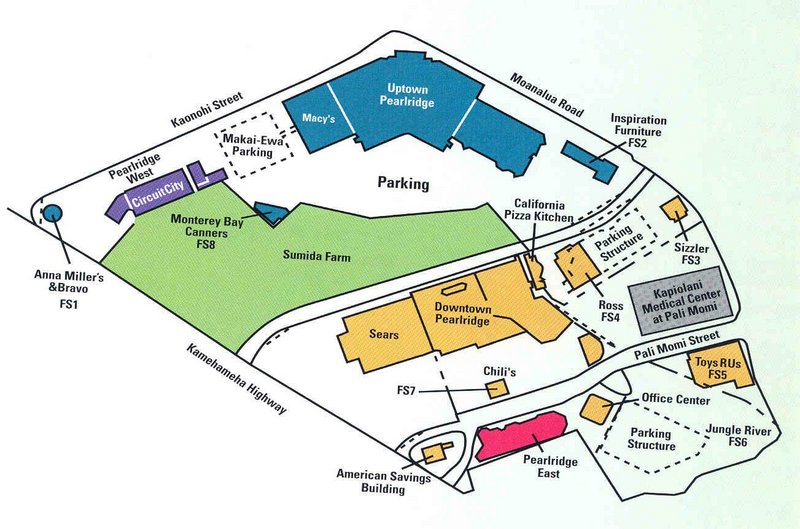

Today, Windward Mall, portions of Windward Community College, Valley of the Temples, Tetsuo Harano Tunnels (H3,) Hawaiʻi Institute for Marine Biology, MCBH, Heʻeia Kea Small Boat Harbor and a bunch of other folks call Heʻeia home.