by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

“Whereas, Marcus C Monsarrat, a naturalized subject of this Kingdom, is guilty of having perpetuated a grievous injury to Ourselves and to Our Royal family”.

“(We) do hereby order that the said Marcus C Monsarrat be forthwith expelled from this Kingdom; and he is hereby strictly prohibited, forever, from returning to any part of Our Dominions, under the penalty of Death.” King Kamehameha IV and Kuhina Nui Victoria Kamāmalu (May 20, 1857)

Whoa … let’s look back.

Marcus Cumming Monsarrat was born in Dublin Ireland on April 15, 1828. He is a descendant of Nicholas Monsarrat of Dublin, who went to Ireland from France in 1755.

Marcus made his home in Canada before coming to Hawaiʻi and was admitted as a member of the Law Society of Upper Canada, June 18, 1844, at Osgoode Hall, Toronto.

He came to the Islands in 1850.

He was deputy collector of customs and later entered the lumber firm of Dowsett & Co, which was eventually absorbed by SG Wilder & Co.

Marcus married Elizabeth Jane Dowsett; their children were, James Melville Monsarrat (1854-1943,) Marcus John Monsarrat (1857-1922,) Julian Monsarrat (1861-1929,) Kathleen Isabell Monsarrat (1863-1868,) William Thorne Monsarrat (1865-1924) and Samuel Archibald Monsarrat (1868-1956.)

Prince Lot had invited Marcus Monsarrat, who lived nearby, as a guest at a dinner party on January 15, 1857. Two weeks before, Monsarrat led a group of merchants in presenting a new carriage to Queen Emma on her 21st-birthday.

When dinner was over, Monsarrat bid his goodbye and left.

So far, so good – so, why the expulsion? … It’s what happened next ….

Soon after, one of Lot’s servants said the tall, handsome Monsarrat was in Victoria Kamāmalu’s bedroom. (Kanahele)

Prince Lot burst into Victoria Kamāmalu’s quarters and discovered her in compromising circumstances with his guest Marcus Monsarrat (he was ‘arranging his pantaloons.’) (KSBE)

Lot ordered him to leave and threatened to kill him. Later, the King blamed Lot for not ‘shooting Monsarrat like a dog.’ (Kanahele)

The king then “commanded (Marshal WC Parke,) in pursuance of Our Royal order, hereto annexed, forthwith to take the body of MC Monsarrat, and him safely convey on board of any vessel which may be bound from the port of Honolulu to San Francisco, in the State of California”. (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 28, 1857)

On Wednesday, May 20, Mr. Monsarrat was led to believe he would be allowed to remain in Honolulu long enough to settle up his affairs, and would for that purpose be granted his liberty on parole – this was declined. (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 27, 1857)

“At half past three o’clock, Thursday morning, Mr Monsarrat was conducted by the Marshal and Sheriff and a guard of forty soldiers to the steamer, which had her steam up and ready for sea.”

“On leaving the palace, Mr M was told that resistance on his part would be of no use, that the orders issued in regard to him were peremptory, and if any attempt to escape was made, he would have to be treated as a culprit. He assured those having charge of him that he had no idea of resisting, and would yield to the superior force placed over him.” (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 28, 1857)

Monsarrat refused to pay for his passage; whereupon Parke paid the captain $80. The King sent over $100 to be given to Monsarrat, that he might not say he was sent off without means. This he declined. (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 27, 1857)

The incident was embarrassing to the court because efforts were underway to arrange a marriage between Victoria Kamāmalu and Kalākaua; these plans were quickly aborted. (Kanahele)

Two years later (May 20, 1859,) the King reduced the sentence to seven years (the King “Being … moved by a feeling of deep sympathy” for the Monsarrat family.)

However, he was “strictly enjoined and prohibited from returning to any part of Our Domains, before the expiration of the period of banishment.” (Forbes) (When he later returned, the King had him arrested and banished, again. (Kanahele)

Monsarrat returned; he died in Honolulu on October 18, 1871. Some suggest Monsarrat Street near Lēʻahi (Diamond Head) is named for Monsarrat; others say it is for his son, James Melville Monsarrat, an attorney and Judge.

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

The legend of King Arthur (Le Morte Darthur, Middle French for “the Death of Arthur” (published in 1485)) speaks of King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot and the Knights of the Round Table (and foresees “Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone is the rightwise born king of all England.”)

Many tried; many failed.

Legendary Arthur later became the king of England when he removes the fated sword from the stone. Legendary Arthur goes on to win many battles due to his military prowess and Merlin’s counsel; he then consolidates his kingdom. (The historical basis for the King Arthur legend has long been debated by scholars.)

In Hawaiʻi, a couple legends and prophecies relate to a stone, Naha Pōhaku (the Naha Stone.)

Its weight is estimated to be two and one-half tons (5,000-pounds.) The stone was originally located in the Wailua River, Kauai; it was brought to Hilo by chief Makaliʻinuikualawaiea on his double canoe and placed in front of Pinao Heiau. (NPS)

The stone was reportedly endowed with great powers and had the peculiar property of being able to determine the legitimacy of all who claimed to be of the royal blood of the Naha rank (the product of half-blood sibling unions.)

As soon as a boy of Naha stock was born, he was brought to the Naha Stone and was laid upon it – one faint cry would bring him shame. However, if the infant had the virtue of silence, he would be declared by the kahuna to be of true Naha descent, a royal prince by right and destined to become a brave and fearless soldier and a leader of his fellow men. (NPS)

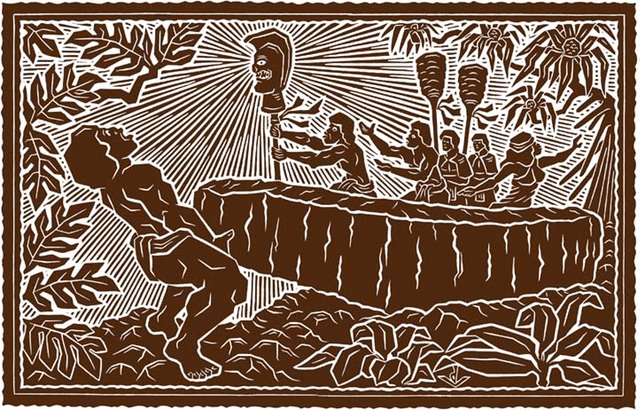

In another instance, Kamehameha traveled from Kohala to Hilo with Kalaniwahine a prophetess, who advised him that there was a deed he must do. Although not of Naha lineage, Kamehameha came to conquer the Naha Stone.

Kalaniwahine proclaimed that if he succeeded in moving Naha Pōhaku, that he would move the whole group of Islands. If he changed the foundations of Naha Pōhaku from its resting place, he would conquer the whole group and he would prosper and his people would prosper.

Kamehameha said, “He Naha oe, a he Naha hoi kou mea e neeu ai. He Niau-pio hoi wau, ao ka Niau-pio hoi o ka Wao.” (”You are a Naha, and it will be a Naha who will move you. I am a Niaupio, the Niaupio of the Forest.”)

With these words did Kamehameha put his shoulders up to the Naha Stone, and flipped it over, being this was a stone that could not be moved by five men. (Hoku o Hawaiʻi, November 1, 1927)

When Kamehameha gripped the stone and leaned over it, he leaned, great strength came into him, and he struggled yet more fiercely, so that the blood burst from his eyes and from the tips of his fingers, and the earth trembled with the might of his struggling, so that they who stood by believed that an earthquake came to his assistance. (NPS)

The stone moved and he raised it on its side.

And, the rest of the history of the Islands has been pretty clear about the fulfillment of the prophecy and unification of the Islands under Kamehameha.

The Naha Stone is in front of Hilo Public Library at 300 Waiānuenue Avenue between Ululani and Kapiʻolani Street (the larger of the two stones there.)

The upright stone sitting to the makai side of the Naha Stone is associated with the Pinao Heiau, one of several that once stood in Hilo. Some of the stones that built the first Saint Joseph church and other early stone buildings in town likely came from Pinao heiau. (Zane)

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

Mai ka hikina a ka Ia i

Kumukahi a ka welona a ka Iā i Lehua.

From the sunrise at Kumukahi to

the fading sunlight at Lehua.

From sunrise to sunset. Kumukahi, in Puna, Hawai‘i, was called the land of the sunrise and Lehua, the land of the sunset. This saying also refers to a life span-from birth to death. (Pukui, #258)

Kumukahi is a place of importance and a place of healing. Practitioners of la‘au lapa‘au often prayed to Kumukahi and his brother Palamoa as “deities of healing” when gathering and applying traditional Hawaiian herbal medicine. These practitioners would face the Hikina (East) and chant their prayers at sunrise from where ever they were living in the islands. (Lopes)

Kumukahi is translated as the ‘beginning/first source, chief, or teacher,’ in reference to the “first source” of wisdom, knowledge or of knowing.

This is because of its location in relation to the sun, Kānehoalani (an akua who is, in one story, Pele’s father) and what the sun represents, as the easternmost point of Hawaiʻi.

It is the beginning of our collective consciousness as people of Hawaiʻi, which establishes Kumukahi as a wahi pana (living and celebrated place) and a wahi moʻolelo (a storied place). (Hawai‘i County)

Kumukahi was also noted as a “leina a ka uhane,” a place where the soul of a person would leap from this world into the next after death. (Lopes)

Kumukahi was named for a migratory hero from Kahiki (Tahiti) who stopped here and who is represented by a red stone. Two of his wives, also in the form of stones, manipulated the seasons by pushing the sun back and forth between them. One of the wives was named Ha‘eha‘e. Sun worshipers brought their sick to be healed here. (Pukui)

In some accounts, Kumukahi is a kolea bird and is referred to as “the messenger of the gods.” According to Pukui, Kumukahi was the name of a “kanaka aiwaiwa,” a divine being who loved sports, especially holua sledding.

For this reason Pele, the akua wahine of the volcano, was fond of him. Kumukahi often produced sporting events in which his people participated. Pele often joined in on these particular festivities in the form of an attractive woman.

However, on one such occasion, Pele, disguised as an old woman, requested to participate and was denied. In her anger, she chased Kumukahi to the sea where she covered him with her lava. (Lopes)

At the tip of Cape Kumukahi were a number of stone cairns, built of the rough lava from the surrounding flow, which are said to have been built by the various monarchs of the Hawaiian kingdom upon assuming the throne. Some reference them as Ki‘i Pōhaku Ali‘i – King’s Pillars.

In 1823, William Ellis and members of the ABCFM toured the island of Hawai‘i seeking out community centers in which to establish church centers for the growing Protestant mission.

Settlement patterns in Puna tend to be dispersed and without major population centers. Villages in Puna tended to be spread out over larger areas and often are inland, and away from the coast, where the soil is better for agriculture. (Escott)

This was confirmed on William Ellis’ travel around the island in the early 1800s, “Hitherto we had travelled close to the sea-shore, in order to visit the most populous villages in the districts through which we had passed.”

“But here receiving information that we should find more inhabitants a few miles inland, than nearer the sea, we thought it best to direct our course towards the mountains.” (Ellis, 1823)

Ellis noted, “The population of this part of Puna, though somewhat numerous, did not appear to possess the means of subsistence in any great variety or abundance; and we have often been surprised to find the desolate coasts more thickly inhabited than some of the fertile tracts in the interior …”

“… a circumstance we can only account for, by supposing that the facilities which the former afford for fishing, induce the natives to prefer them as places of abode; for they find that where the coast is low, the adjacent water is generally shallow.”

When the Lighthouse Board assumed control of Hawai‘i’s lighthouses in 1904, it began work on a plan to erect major lights to better mark approaches to the islands. Funds for Makapu‘u Lighthouse were secured in 1906, money for Molokai lighthouse was obtained in 1907, and Congress made an appropriation for Kilauea Point Lighthouse in 1908.

These aids to navigation were seen as “material benefit to the business .community, to shipping interests, insurance interests and mercantile interests. … [T]he next one we have recommended is for a first order light at Cape Kumukahi, the easternmost point on the Island of Hawaii.” (PCA, Nov 4, 1908)

“There is at present no landfall light for vessels bound to Hawaii by way of Cape Horn. Several vessels have within recent years gone ashore on Kumukahi Point. This is the first land sighted by vessels from the southward and eastward.”

“The shipping from these directions now merits consideration, and with the improvement of business at Hilo the necessity for a landfall light on this cape grows more urgent. It is estimated that a light at this point can be established for not exceeding $75,000, and the Board recommends that an appropriation of this amount be made therefor.” (Report of the Lighthouse Board, 1908)

On December 31, 1928, the US government purchased fifty-eight acres on Cape Kumukahi from the Hawaiian Trust Company for the sum of $500. During the following year, a thirty-two-foot wooden tower capped with an automatic acetylene gas light was built at the cape for local use. It was replaced in 1933 by a 125-foot pyramidical galvanized steel tower. (Lighthouse Friends)

“Life was peaceful for several years along the Puna coastline until a lava flow threatened Kapoho in 1955. [Kumukahi lightkeeper Joe] Pestrella stayed at his post to watch over the lighthouse as the lava advanced.”

“The following year, he received the “Civil Servant of the Year” award from the U.S. Coast Guard for his bravery in staying at his post. At the time, Ludwig Wedemeyer, leader of the Hilo Coast Guard station, noted it was the first time a Hawai‘i Island resident had received such an award from the Coast Guard.” (Laitinen)

On January 12, 1960, over 1,000 earthquakes were recorded near Kapoho Village, just above Kumukahi. The earthquakes grew in size and frequency, creating large fractures along the Kapoho Fault overnight. The 1960 Kīlauea eruption began on the night of January 13.

For the first two weeks, Kapoho village remained virtually intact except for a blanket of pumice and ash that covered everything. The lava flow issuing from the growing cinder cone was moving in the opposite direction of town.

Things changed on January 27th when very fluid lava poured from the vents and fed massive ‘a‘ā flows that moved southwestward through the streets of town. By midnight, most of Kapoho had been destroyed.

By January 28, lava destroyed Coast Guard residences near Cape Kumukahi, but the lighthouse was spared. The Koa‘e Village fell victim to lava flow progression, losing the community hall, a local church and one residence. The eruption stopped February 19. (USGS)

“After the 1960 eruption ended, an electric line was run from Kapoho Beach Lots to the lighthouse to restore power, and the light became automated. Joe was transferred to a lighthouse on O‘ahu, and when he retired in 1963, he was the last civilian lighthouse keeper in Hawai‘i.” (Laitinen)

With prevailing NW trade winds and nothing between it and the America continents, except thousands of miles of open ocean, Kumukahi has some of the cleanest air in the Northern Hemisphere.

The Kumukahi light tower is also used as a monitoring station to test air quality. Since 1993, scientists have been taking ambient air samples every week for chemical analysis.

The long-term data records supplied by these samples are fundamental to understanding changes in atmospheric composition of gases affecting stratospheric ozone, climate and air quality, and provide an avenue to detect unexpected changes in these chemicals.

The 2018 eruptions interrupted the sampling efforts and NOAA scientists have undertaken novel development of an uncrewed aircraft system (UAS) “hexacopter” that will enable the lab to not only recommence a long-standing mission that was recently forced to halt, but paves the way toward enhanced operations in the future. (NOAA)

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

A fishpond symbolized a rich ahupua‘a (major land division), which reflected favorably on the ali‘i as well as on the people living in the ahupua‘a.

There are two general types of fishponds, saltwater and freshwater, with six main styles. The style of fishponds constructed is closely related to the topographical features of an area.

The salinity of the water served as an important element determining type of construction as well as what types of food that could be raised and their level of productivity.

The six main styles of fishponds as identified by Kikuchi include: Loko Kuapā, Loko Pu‘uone, Loko Wai, Loko I‘a Kalo, Loko ‘Ume‘iki and Kāheka / Hāpunapuna.

The first three types of coastal fishponds – Loko Kuapā, Loko Pu‘uone, and Loko Wai – belonged to royalty. These ponds, between 10 and 100 acres in size, were considered a symbol of high social and economic status.

Loko Kuapā

A fishpond of littoral water whose side or sides facing the sea consist of a stone or coral wall usually containing one or more sluice grates.

Loko kuapā (Figure 1, Type 1) were strictly coastal fishponds whose characteristic feature was a kuapā (seawall) of lava or coral rubble. They were usually built over a reef flat, with the wall extending out from two points on the coast in an enclosed semicircle.

These ponds usually had one or two ‘auwai (channels) that were used mainly for water flushing or inflow, depending on the rising and ebbing of the tides, but were also used during harvesting and stocking.

Loko kuapā, because they were enclosed reef flats, had all the marine aquatic sea life that would be expected to be found on a reef flat including kala, palani, and manini.

Less common fish sometimes found in these fishponds were the kāhala, kumu, moano, weke ula, uhu, various species of hīnālea, surgeonfish, crevally, goatfish, and even puhi.

Loko Pu‘uone

An isolated shore fishpond usually formed by the development of barrier beaches building a single, elongated sand ridge parallel to the coast and containing one or more ditches and sluice grates.

Loko pu‘uone contained mostly brackish water, with inputs from both freshwater and saltwater sources. Fresh water from streams, artesian springs, and percolation from adjacent aquifers was mixed with seawater that entered through channels during incoming tides.

This mixing produced a highly productive estuarine environment. The most characteristic feature of this type of fishpond was a sandbar, coastal reef structure, or two close edges of landmass that could be connected to enclose a body of water.

Typical of these ponds were fish that were able to handle fluctuations of salinity. These fish include ‘ama‘ama, awa, āholehole, pāpio or ulua, ‘ō‘io, nehu, awa ‘aua, ‘o‘opu, kaku, moi, and weke.

Loko Wai

An inland freshwater fishpond which is usually either a natural lake or swamp, which can contain ditches connected to a river, stream, or the sea, and which can contain sluice grates.

It was typically made from a natural depression, lake, or pool whose water was mainly from diverted streams, natural groundwater springs, or percolation from an aquifer. Various ‘o‘opu were commonly found in these ponds.

Loko I‘a Kalo

An inland fishpond utilizing irrigated taro plots. These “kalo fishponds” combined aquaculture with flooded agriculture. Kalo lo‘i were used to raise ‘o‘opu, ‘ama‘ama, and āholehole.

Research has suggested that diversion of stream runoff for the irrigation of kalo eventually led to fish aquaculture. Irrigated agriculture in lo‘i was enhanced by including fish (loko i‘a kalo), and this led to pure fishpond aquaculture – loko pu‘uone.

Loko ‘Ume‘iki

Loko ‘ume iki were not actually fishponds but rather fish traps. Like the loko kuapā, they were constructed on a reef flat, but loko ‘ume iki had “fish lanes,” corridors used to net or trap fish going onto or off the reef.

Each loko ‘ume iki had many fish lanes with fishing rights usually assigned to a family. The traps operated without the use of gates and relied on natural movements of fish.

The lanes were usually tapered, with the wide end facing either inward or outward, and anywhere from 10 to 40 feet long.

Kāheka and Hāpunapuna

A natural pool or holding pond. These fishponds are also referred to as anchialine ponds. They have no surface connection to the sea, contain brackish water and show tidal rhythms. Many have naturally occurring shrimp and mollusks.

Most Hawaiian anchialine ponds are in the youngest lava areas of the Big Island of Hawaiʻi and Maui. They exist in inland lava depressions near the shore and contain brackish (a mixture of freshwater and saltwater) water.

Freshwater is fed to the ponds from ground water that moves downslope and from rainwater. Ocean water seeps into the ponds through underground crevices in the surrounding lava rock. (Lots of information here is from DLNR and Farber.)