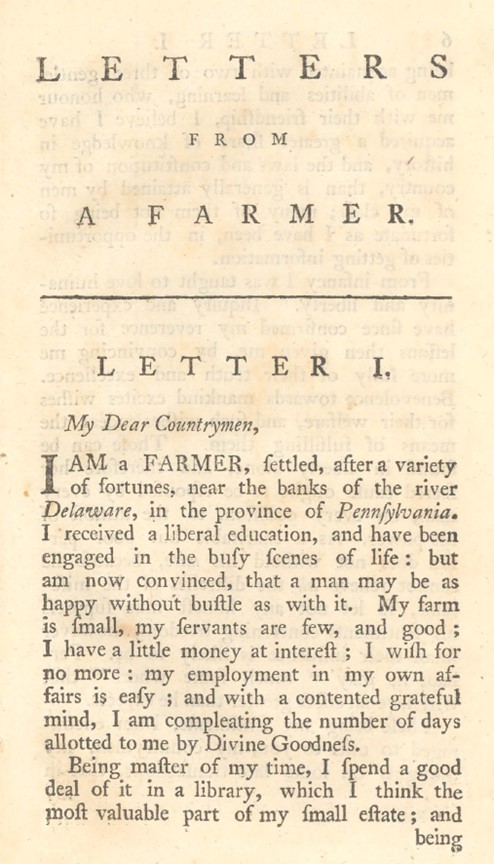

John Dickinson, a Philadelphia lawyer and wealthy landowner, wrote twelve “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania: to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies” began to appear in the Pennsylvania Chronicle and Universal Advertiser on December 2, 1767, under the simple pseudonym ‘a Farmer.’

Using constitutional argument laced with political economy, Dickinson sought to persuade everyone who read his words, on either side of the Atlantic, of both the economic folly and the unconstitutionality of ignoring the rights of Englishmen living in the American Colonies.

The letters first appeared in the newspapers over a period of ten weeks in late 1767 and early 1768.

Letter One (December 2, 1767) introduced the small, fictional farmer, with a few servants and a small amount of investments, and then launched into an attack on the threat to the New York legislature, warning the other colonies that without unity of resistance to such efforts, all may fall separately.

Letter Two (December 7, 1767) took to task the Revenue Act as unconstitutional. “The Farmer” went on to argue for free trade and the end of taxes on goods that the colonies are not allowed to manufacture and must import from the homeland.

Letter Three (December 14, 1767) appealed strongly for a peaceful and dignified settlement of arguments between colonies and Crown, and displayed Dickinson’s respect for order which marked all of his opinion in years to come.

Letter Four (December 21, 1767) discussed taxes and the right to representation before any taxes – internal or external – were to be levied.

Letter Five (December 28, 1767) asked why there was this sudden departure from the traditional since taxes were now being passed for the sole task of raising revenue from the colonies. “The Farmer” blamed those who had proposed them for alienating the affections of the Kings’ subjects.

Letter Six (January 4, 1768) remarked upon the ways that “all artful rulers” extend their power unconstitutionally and warned the colonies to be ever vigilant of what future actions from the Parliament might mean.

Letter Seven (January 11, 1768) reiterated that although taxes may be small and the burden tolerable in business terms, the precedent is the fatal danger that makes the colonists, in effect, slaves.

Letter Eight (January 18, 1768) reinforced the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation, especially concerning the way that the government spends the money raised, quite possibly in ways not helpful, or even dangerous, to those who pay them.

Letter Nine (January 25, 1768) lectured fellow colonists on the vital need for local representation and firmly established assemblies.

Letter Ten (February 1, 1768) was another warning, this time against the dangers of the current hostile atmosphere in the British Parliament and the logical progression of tyranny (citing Ireland), after precedent has been set and allowed to stand.

Letter Eleven (February 8, 1768) again dealt with precedent, and said that new unconstitutional designs of government must be recognized and halted immediately, before they become entrenched.

Letter Twelve (February 15, 1768) wound up the series with the common sense argument that all colonies and legislatures must be united in opposition to all attempts to install unconstitutional precedent, even though all interests may not be individually served.

Click the link to view the letters and/or hear an audio reading of each: https://tinyurl.com/u3n8uyp9

The letters were quickly published in pamphlet form, reprinted in almost all colonial newspapers, and read widely across the colonies and in Britain.

There is little doubt that the flood of petitions and calls for boycotts on imported goods up and down the colonies owed much to these letters. Perhaps most importantly, the concept of unity started to take root.

Dickinson himself blamed the New England colonies for escalating affairs to undignified violence and held the fleeting opinion later that Boston had brought its troubles on itself.

Nevertheless, the eventual result was the calling of the Continental Congress and the unity of purpose that John Dickinson had advocated, though certainly not in the directions that he had argued in his letters and would continue to argue at the Congress. (John Osborne, Dickinson University)

Click the following link to a general summary about Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania:

Leave your comment here: