Thomas ap Catesby Jones was born April 24, 1790 to Major Catesby and Lettice Turbeville Jones at Hickory Hill in Westmoreland County, Virginia. (The ‘ap’ in his name is a Welch prefix noting he is ‘Thomas, the son of Catesby Jones.’)

His father died September 23, 1801, leaving six children and a widow; she died in mid-December 1804. Thomas went to live with an uncle – who later died from injuries suffered in a duel.

Then, Thomas received an appointment as a midshipman and joined the US Navy (at the time, 1805, it had only 29-vessels.) He moved up through the ranks. (Smith)

He later fought in the War of 1812; with five gunboats, one tender and a dispatch boat headed toward the passes out to Ship Island, to watch the movements of the British vessels. This little flotilla, barely enough for scout duty at sea, was the extent of the naval forces in the Gulf waters.

A British flotilla of barges started coming from the direction of the enemy’s ships, evidently to overtake and attack the gunboats with 1,200-men and 45-pieces of artillery. The American defensive forces were seven small gunboats, manned by 30-guns and 180-men.

The battle was fiercely fought for nearly two hours, when the American gunboats, overpowered by numbers, were forced to surrender, losing 6-men killed and 35-wounded, among the latter Jones (he was one struck in the shoulder, “where it has remained ever since.”) Several barges of the enemy were sunk, while their losses in killed and wounded were estimated at two to three hundred. (Smith)

These results show that the victory of the British was a costly one. Although wounded and captured, Jones received commendation for delaying the British advance that culminated in the Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815,) the final major battle of the War of 1812 when the Americans prevented the British from taking New Orleans.

Later, Jones went to the Islands.

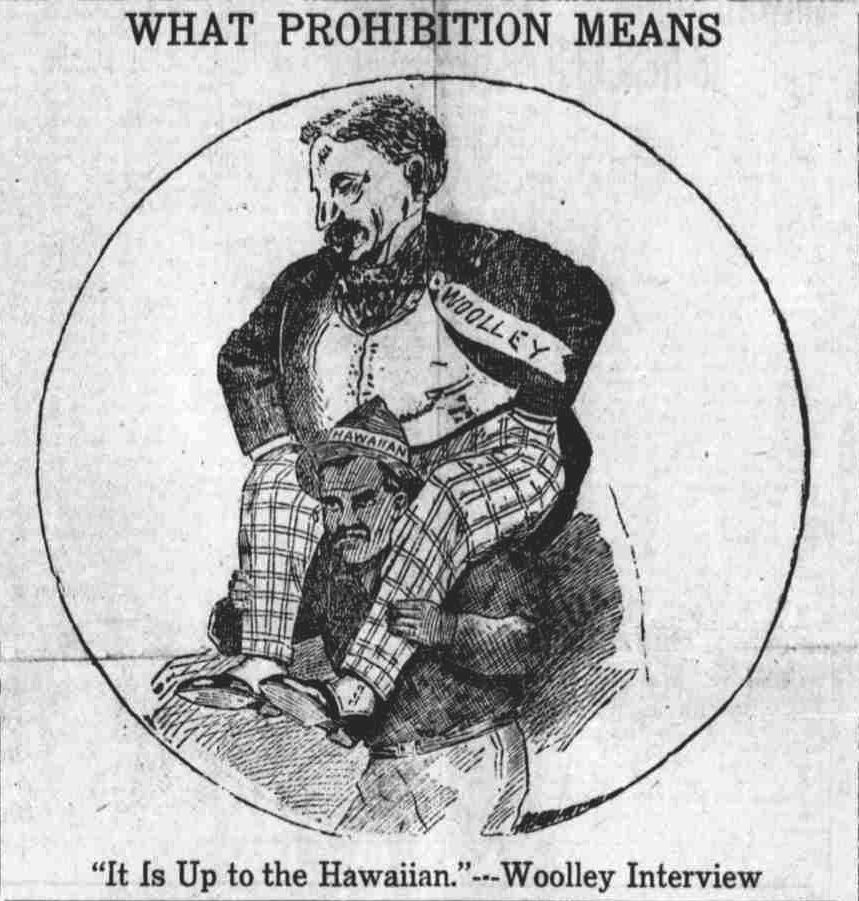

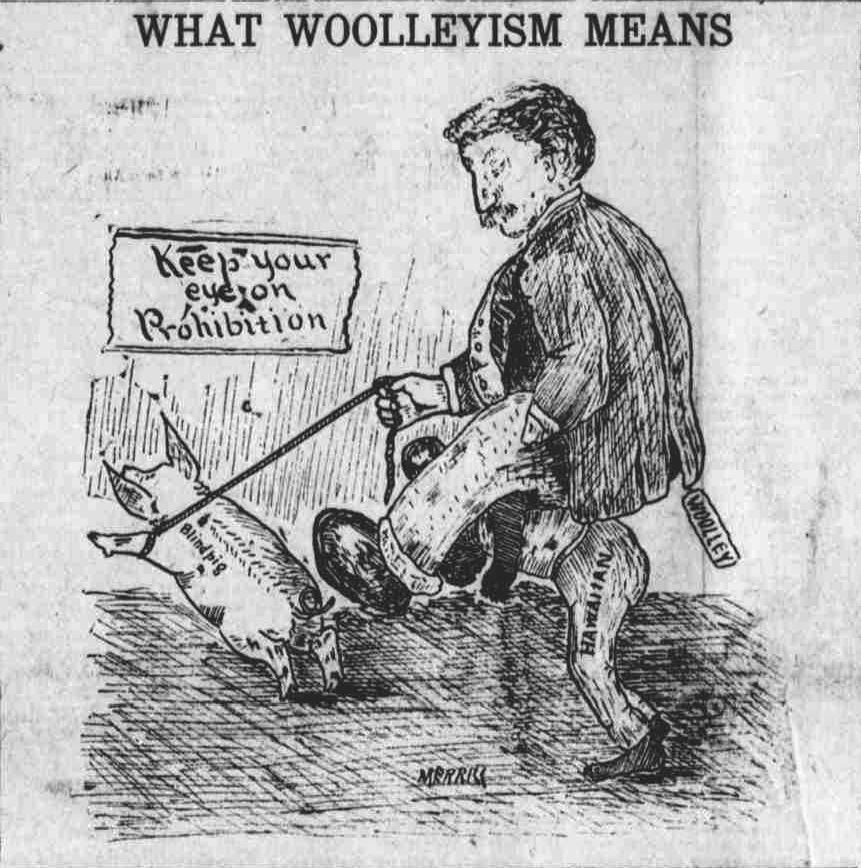

Growing concerns over treatment, safety and attitudes toward American sailors (and therefore other US citizens in the Islands) led the US Navy to send Jones to the Islands, report back on what he learned, banish the bad-attitude sailors and maintain cordial relations with the Hawaiian government.

“The object of my visit to the Sandwich Islands was of high national importance, of multifarious character, and left entirely to my judgment as to the mode of executing it, with no other guide than a laconic order, which the Government designed one of the oldest and most experienced commanders in the navy should execute”. (Jones, Report of Minister of Foreign Affairs)

“Under so great a responsibility, it was necessary for me to proceed with the greatest caution, and to measure well every step before it was taken; consequently the first ten or fifteen days were devoted to the study and examination of the character and natural disposition of a people who are so little known to the civilized world, and with whom I had important business to transact.”

“The Sandwich Islanders as legislators are a cautious, grave, deliberate people, extremely jealous of their rights as a nation, and are slow to enter into any treaty or compact with foreigners, by which the latter can gain any foot-hold or claim to their soil.”

“Aware of these traits in the character of the Islanders with whom I had to negotiate, I determined to conduct my correspondence with them in such a manner as at once to remove all grounds of suspicion as to the object and views of the American Government, and to guard against misrepresentation and undue influence”.

“(I also wanted to) give the Chiefs and others in authority, the means of understanding perfectly the nature of my propositions, I took the precaution to have all official communications translated into the Oahuan language, which translation always accompanied the original in English”.

“(B)y giving them their own time to canvass and consult together, I found no difficulty in carrying every measure I proposed, and could I have been fully acqainted with the views of my government, or been authorized to make treaties, I do not doubt but my success would have been complete in any undertaking of that character.” (Jones Report to Navy Department, 1827)

Jones’s resolved the sailor desertion issue, the chiefs agreed to pay in full the debts and then Jones negotiated ‘Articles of Arrangement’ noting the “peace and friendship subsisting between the United States and their Majesties, the Queen Regent and Kauikeaouli, King of the Sandwich Islands, and their subjects and people,” (later referred to as the Treaty of 1826, the first treaty signed by the Hawaiians and US.)

Jones elevated the image of America … protesting the agreement His Britannic Majesty’s Consul-General, Captain Richard Charlton declared the islanders to be mere tenants at will, subjects of Great Britain, without power to treat with any other State or Prince, and that if they entered into treaty stipulations with the United States, Great Britain would soon assert her right by taking possession of the Islands. (Jones Report to Navy Department, 1827)

Jones asked Charlton what was the nature or character of the commission he bore from the King. The response, “Consul-General to the Sandwich Islands.” Jones followed up with, ‘What are the duties or functions of a Consul-General?’ (The answer was in accordance with the acknowledged international understanding of the office.)

He then asked Charlton if it was customary for a Prince or Potentate to send Consuls, Consuls-General or Commercial Agents, to any part or place within his own dominions? Charlton had no answer.

When informed of all that had been said between Jones and Charlton, Kalanimōku, noted, “It is so…. Is America and England equal? We never understood so before. We knew that England was our friend and that Capt Charlton was here to protect us, but we did not know that Mr Jones, the Commercial Agent, was the representative of America – we thought he was for trade only.” (Jones Report to Navy Department, 1827)

“Capt. Jones, as a public officer, carefully sought to promote the interests of commerce and secure the right of traders, pressed the rulers to a prompt discharge of their debts, and negotiated articles of agreement with the government for the protection of American interests”.

He “secured for himself among the people the designation of ‘the kind-eyed chief’ – a compliment falling on the ear of many of different classes”. (Hiram Bingham)

Jones later commanded the US Pacific Squadron, fought in the Mexican American War and later in his career, however, Jones was court-martialed for oppression of seamen and mishandling of Navy funds on the coast of California in the wild days of the Gold Rush. Jones denied all charges. (Gapp) (He was later reinstated and his pay was restored.) He died May 30, 1858.