The Hawaiian Islands were formed as the Pacific Plate moved westward over a geologic hot spot. Oʻahu is dominated by two large shield volcanoes, Waiʻanae and Koʻolau that range in age from two to four-million years old.

The younger volcanic craters are all less than 500,000 years old. They formed after Oʻahu had moved well off the hot spot and the main shield volcanoes had gone dormant for at least two-million years.

Scientists say Lēʻahi (Diamond Head) (one of these later eruptions) is a tuff cone, formed by hydromagmatic activity. Tuff is a volcanic rock made up of a mixture of volcanic rock and mineral fragments. Wherever there are explosive volcanic eruptions you can expect to find tuff. (SOEST)

A hundred years ago, Hawaiʻi missionary Reverend Sereno Bishop noted Diamond Head was made in less than an hour’s time and is “composed not of lava, like the main mountain mass inland, but of this soft brown rock called tuff.” (Bishop, Commercial Advertiser, July 15, 1901)

Others noted, “the duration of eruption of Diamond Head was of the order of five hours. The eruption may have been intermittent with interruptions sufficient to extend the whole period of activity to as much as five days, but probably not more.” (Wentworth, Bishop Museum, 1926)

“Volcanic eruptions may be distinguished into two classes, the effusive and the explosive. In the former the molten rock is poured out and covers the mountain slopes with great floods.”

“If you look up at the sides of yonder ravines (on the Koʻolau mountains,) which the rainstorms of many hundred thousands of years have worn out of the original dome-shaped mountain, you will see the back edges of the ancient lava streams lying in layers.”

“The tuff cones are entirely different, and are produced by very brief and sudden explosive eruptions. The tuff was violently shot high aloft into the air in the form of superheated mud. This hot mud cooled and thickened by the expansion of its water and its partial escape as steam before reaching the ground.”

“It hardened and cemented as it fell, though still liquid enough to form in thin layers or laminations as we see it lying around us at the base of the hill. … The tuff-fountain escaping from its confinement, at once expanded and spread out like a vast tree.”

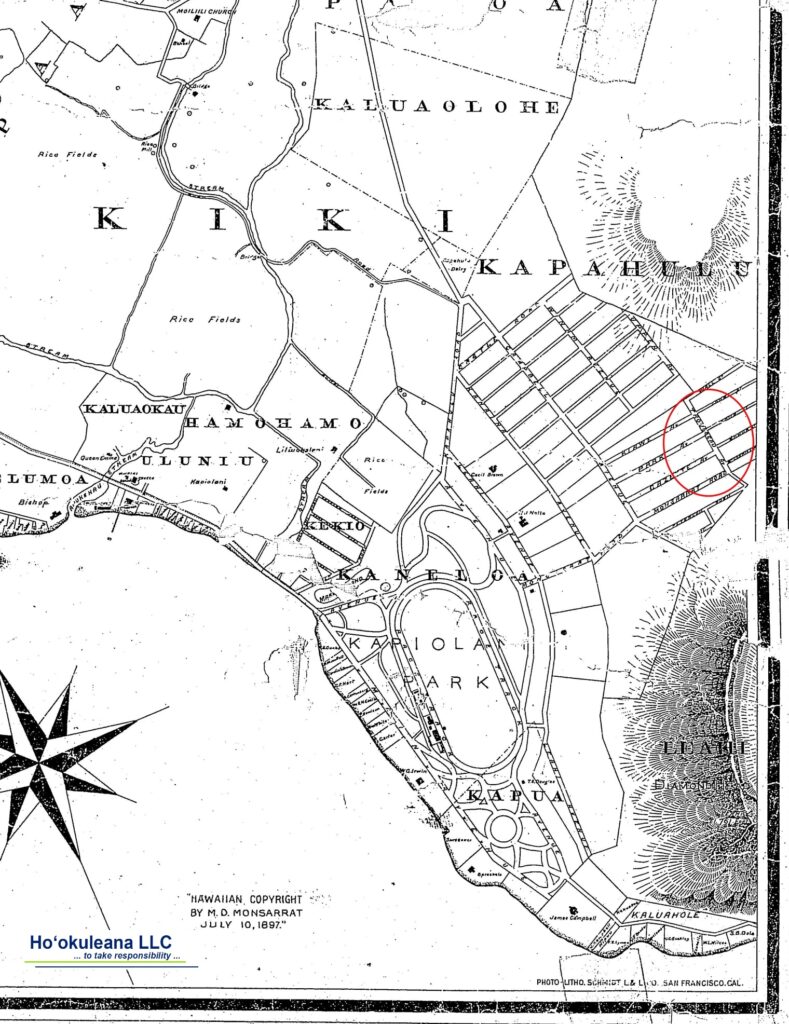

“Here at Diamond Head, which is one mile in diameter, the bulk of the mud spread out half a mile in all directions before ending its fall. Thus a very exact circular ring was piled up of one mile in diameter. There was, however, another influence, that of a violent easterly-wind which deflected the entire fountain westward”.

“The wind also acted with especial force upon the highest part of the fountain, flinging and piling it up on the western side of the crater in a lofty cone. A large part of that cone has been weathered away by the impact of rainstorms upon the soft rock; but it still stands in a peak some 200 feet higher than the main run.”

“The vent or point of issue of the tuff-fountain must have been at the lowest point of the interior, where lies the present pond of water.” (Bishop, Commercial Advertiser, July 15, 1901) (The same series of eruptions produced Punchbowl and Koko Head Crater.)

Somewhat more than half of the craters of southeast Oahu are arranged in linear groups, those dominated by the craters Tantalus, Diamond Head, and Koko Crater. In the Diamond Head group is the main Diamond Head vent, Kaimuki crater and Mauʻumae crater.

(A cinder cone is a volcanic cone built almost entirely of loose volcanic fragments called cinders or pumice that accumulate around and downwind from a vent.)

(Cinders are glassy and contain numerous gas bubbles “frozen” into place as magma exploded into the air and then cooled quickly.) (USGS)