Despite its moniker, “Large Slow Target,” the ‘Landing Ship, Tank’ (LST) was an important naval vessel created during World War II to support amphibious operations by carrying significant quantities of vehicles, cargo and landing troops directly onto an unimproved shore.

An LST, 382-feet long and 50-feet wide, carried a crew of 8-10 officers and 115 enlisted men; in addition, there were berths for over 200-troops and a capacity to carry a 2,100-ton load of tanks, trucks, jeeps and weapon carriers and associated munitions and supplies.

1,051 LSTs were constructed and used in the war effort; they were used in the Atlantic and the Pacific. Only 26 were lost in WWII due to enemy action.

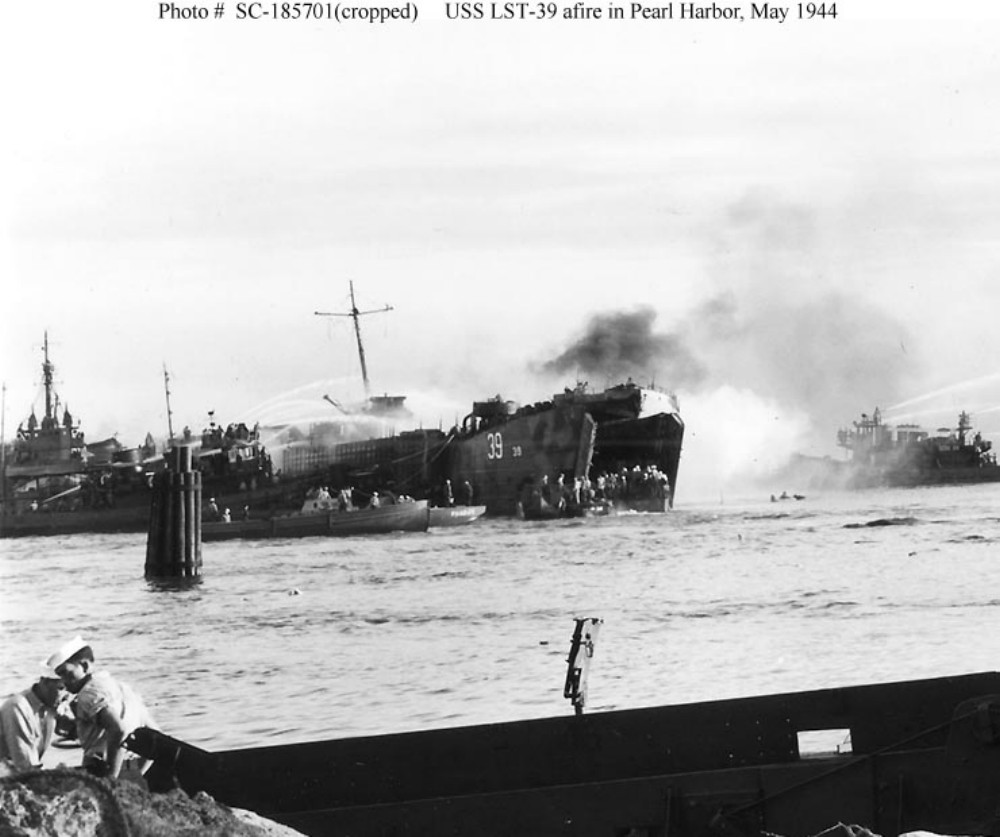

However, in Hawaiʻi, a once secret and often-forgotten tragedy struck at Pearl Harbor, in 1944.

At the time, the Allied forces were preparing for two assaults – one was in the Atlantic (D-Day, June 6, 1944 – nearly 200,000-Allied troops on 7,000-ships and more than 3,000-aircraft headed toward Normandy, France.)

The other was in the Pacific (Saipan, June 15, 1944 – more than 300-landing vehicles put 8,000-Marines on the west coast of Saipan; eleven support ships covered the Marine landings.)

In preparation for the Saipan assault, in late-May, crews were loading ships at the US Pacific Fleet base at West Loch, Pearl Harbor.

(Pearl Harbor is divided into a series of lochs that fan out from Ford Island that sits in the center of harbor. West Loch was the staging area for the invasion fleets of the Pacific.)

29-LSTs, plus a variety of other amphibious vessels that would support the initial landings and follow-on operations, were tightly clustered while their hulls and decks were being filled with ammunition, supplies and other material.

That list of items included munitions of all calibers and types, propellants, aviation gasoline, vehicle fuel and a variety of other volatile cargoes.

Nested beam-to-beam at piers off of Hanaloa and Intrepid Points opposite Lualualei (now known as Naval Magazine Pearl Harbor) were six compact rows of LSTs and other craft moored at “Tare” piers jutting into the adjoining waters of West Loch and Walker Bay.

At 1508 (3:08 pm) May 21, 1944, Lualualei’s tranquility was shattered by a deafening explosion which thundered across most of Oʻahu.

Without warning, an enormous mushroom of orange black fire encapsulated LST-353 at Tare 8, obliterating it and most of the seven other ships from view as the giant fireball burst into the cloudless sky. (Oliver)

The explosions continued, damaging more than 20 buildings shoreside at the West Loch facility. For 24-hours fires raged aboard the stricken ships. (NPS)

Had the Japanese struck again – another sneak attack on Pearl Harbor? … No one knew.

Then the ground shook to a second blast. Earthquake? Volcano? Aerial bombs? Alarms rang as another shattering blast of even greater magnitude jolted the air. (Oliver)

Predictably, flaming gasoline and exploding ammunition soon began to take a frightful toll of the Soldiers, Sailors and Marines loading and manning the ships.

Fires and explosions drove back ships and craft engaged in firefighting efforts, each time those vessels re-entered the inferno to contain the fires and keep the disaster from spreading to the rest of the Fleet anchorage. (USNavalInstitute)

Several investigations sought to find the reason for such a disaster, but no conclusive evidence as how it occurred was decided upon. Two major causes emerged as most likely: Either a fused mortar round was accidently dropped while unloading the LCT aboard LST-353, or the initial explosion was caused by gasoline vapors. (Oliver)

The Navy put a “Top Secret” status on the tragedy. Survivors and eyewitnesses to the calamity were warned under threat of prosecution not to make any mention of the disaster in letters or calls to family members. To the outside world the tragedy at West Loch simply never happened. (Oliver) (It was declassified in 1960.)

The total casualties were 392 dead; 163 sailors, the rest young Marines from the newly formed 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, and 396 injured – eight ships were lost.

It was recommended that LSTs no longer be nested, so that disaster like that at West Loch could be avoided. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz disagreed. He felt that facilities were too limited at Pearl and that the nesting was necessary. “It is a calculated risk that must be accepted.” (NPS)

Despite the losses, the Saipan invasion force put to sea as scheduled on June 5, 1944, just as the largest invasion armada ever to sail was crossing the English Channel en route to the Normandy beaches.

On June 15, 1944, during the Pacific Campaign of World War II (1939-45,) Admiral Turner was in charge of the assault on Saipan. At 05:42, his orders came – “Land the landing force.” In position, about 1,250 yards from the line of departure, 34-LSTs moved into line. Two huge doors on the bow of each ship opened and dropped their ramps into the water. (BattleOfSaipan)

US Marines (having earlier trained at Camp Tarawa, Waimea, Hawaiʻi Island and Camp Maui, Ha‘ikū, Maui) stormed the beaches of the strategically significant Japanese island of Saipan, with a goal of gaining a crucial air base from which the US could launch its new long-range B-29 bombers directly at Japan’s home islands.

Facing fierce Japanese resistance, Americans poured from their landing crafts to establish a beachhead, battling Japanese soldiers inland and forcing the Japanese army to retreat north. Fighting became especially brutal and prolonged around Mount Tapotchau, Saipan’s highest peak, and Marines gave battle sites in the area names such as “Death Valley” and “Purple Heart Ridge.” (history-com)

This was the first action of Operation Forager, the conquest of the Marianas, consisting of two Marine Divisions, a US Army Division, and the required force and support units from an amphibious armada of nearly 600-ships and craft.

When the US finally trapped the Japanese in the northern part of the island, Japanese soldiers launched a massive but futile banzai charge. On July 9, the US flag was raised in victory over Saipan. (history-com)