The first temperance movement emerged in New England as clergy began to equate drinking alcohol with sins like Sabbath breaking and blasphemy. In 1808, the first temperance society was formed, but it singled-out hard liquor, such as rum, as its only target.

Very early in the temperance movement of Reverend Thomas P Hunt, a Presbyterian minister organized a children’s organization called ‘The Cold Water Army.’ In 1831, the large and influential American Temperance Union urged everyone to only drink cold water (not alcoholic beverages) and take a Cold Water Pledge.

Although Kamehameha III broke it regularly, he made intermittent appeals for abstinence among his fellows. For some years in the 1840s, no liquor was served at official functions. (Daws)

Pūʻali Inuwai (“The water drinking host”) was formed on March 15, 1843 – the Cold Water Army – Hawaiʻi’s version of the Temperance Movement.

Following the model elsewhere, they first looked at the children, suggesting: if you had 100 drunkards and tried to reform them, you would be lucky to save maybe 10; however, if you had 100 children and taught them temperance from a young age, you could save 90 out of the 100.

Hawaiʻi youth were encouraged to join. Thousands of children enlisted in the ‘cold water army.’ Once a year they came together for a celebration. They had a grand time on these anniversary occasions. (Youth’s Day Spring, January 1853)

The Cold Water movement apparently saw some early success. “Recruits to strengthen the ranks of the cold water army, adds real force to this nation; and not-only to this nation, but to every other nation where the principles of total abstinence are making progress. Formerly the Sandwich Islanders were a nation of drunkards; but, as a nation, they are now tee-totallers.” (The Friend, 1843)

However, as time went on the push toward prohibition waned. From the 1850s, it was legal to make wine. In 1864-1865, acts were passed permitting legal brewing of beer and distillation of spirits under license at Honolulu. (Daws)

Later, in hopes that free drinking water would entice sailors to stay out of nearby grog shops, “The Temperance Legion has caused to be erected a Drinking Fountain at the corner of King and Bethel streets, on the Bethel premises – a neat and ornamental fountain. … ‘Free to all.’” [dedicated, June 15, 1867] (The Friend, June 1, 1867)

Through the 1870s, Honolulu was the only place in the kingdom where liquor could be sold legally (another instance of the attempt to isolate vice,) but contemporary comment and court reports make it clear that the illegal liquor traffic was brisk everywhere, from Lāhainā and other port towns to the remotest countryside. (Daws)

Honolulu’s The Friend newspaper began as “Temperance Advocate.” Then, it meant to many, moderate-restrained-use of liquor. Not so in all these years. “It meant total abstinence – nay, even prohibition before there was any such term.” (The Friend, 1942)

Then, came prohibition.

On the continent, into the 1900s, Americans debated whether the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages should be legal. Members of the temperance movement sought to reduce drinking – or even eliminate it. The Civil War disrupted the movement temporarily, but after the war ended, supporters resumed its mission with renewed enthusiasm. (US House)

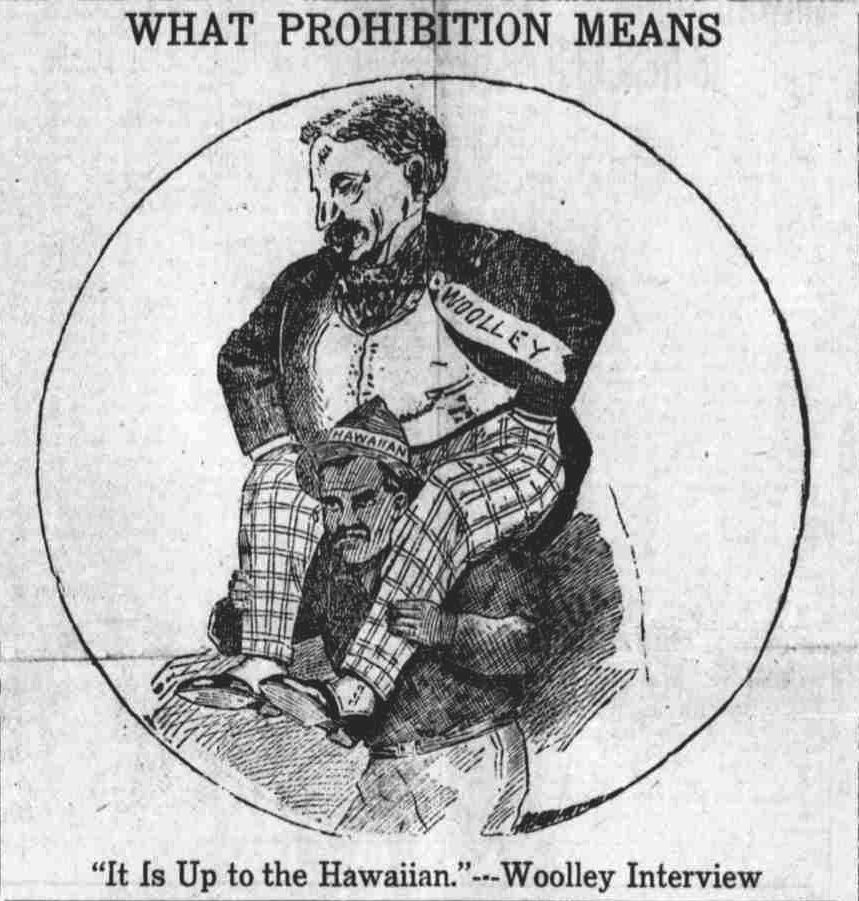

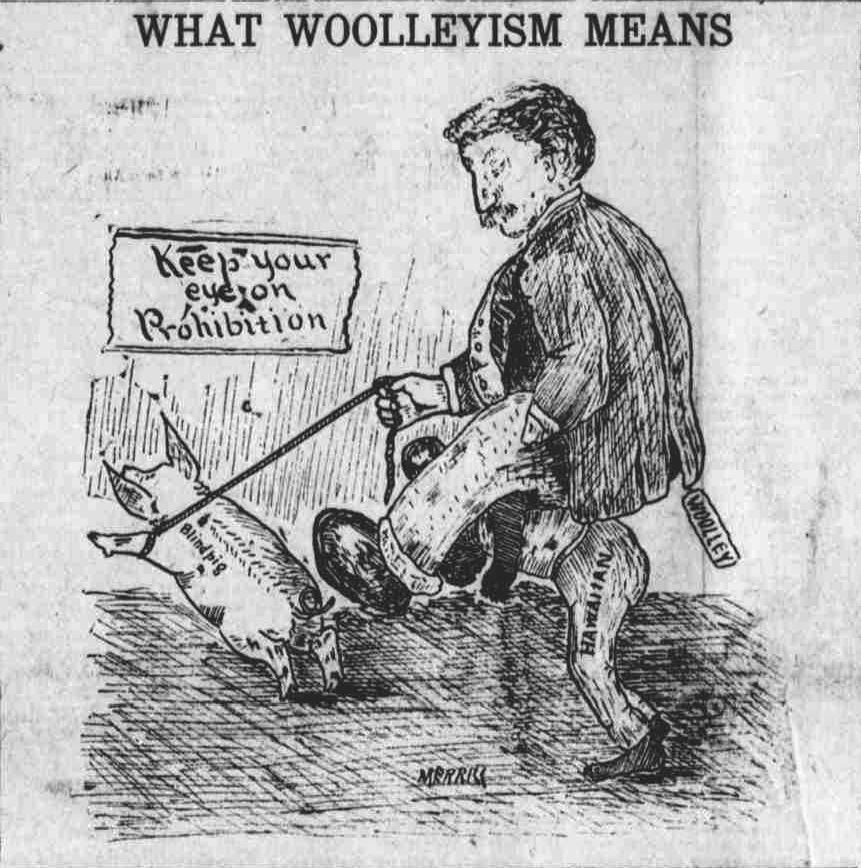

John Granville Woolley was a prominent figure in the American temperance and prohibition movement – he was nominated for the US presidency on the Prohibition party ticket. The Prohibition party – the only party whose principal aim was a ban on the sale of liquor – was founded at a Chicago convention in 1869.

Woolley lobbied for the Prohibition party nationally from the 1880s to the early 1900s and then for the American Anti-Saloon League, a national organization that supported candidates for legislation restricting liquor sales. In 1907, when Woolley vacationed in Hawai‘i, he started a chapter in the Islands. (Hawai’i Digital Newspaper Project)

The Hawaiian legislature passed a liquor licensing law in 1907 in the hope of slowing liquor traffic in the territory. In 1910 Woolley of the Anti-Saloon League of America testified before Congress that the Hawaiian legislature’s licensing law had failed.

Prince Kūhiō stepped in and noted, “There are many good people in Hawaii who believe in prohibition but who do not believe that Congress should enact it.” Woolley pushed Congress to dismantle territorial home rule and Kūhiō fought for home rule. “We are fully capable of settling all our domestic problems,” Kūhiō declared. (US House)

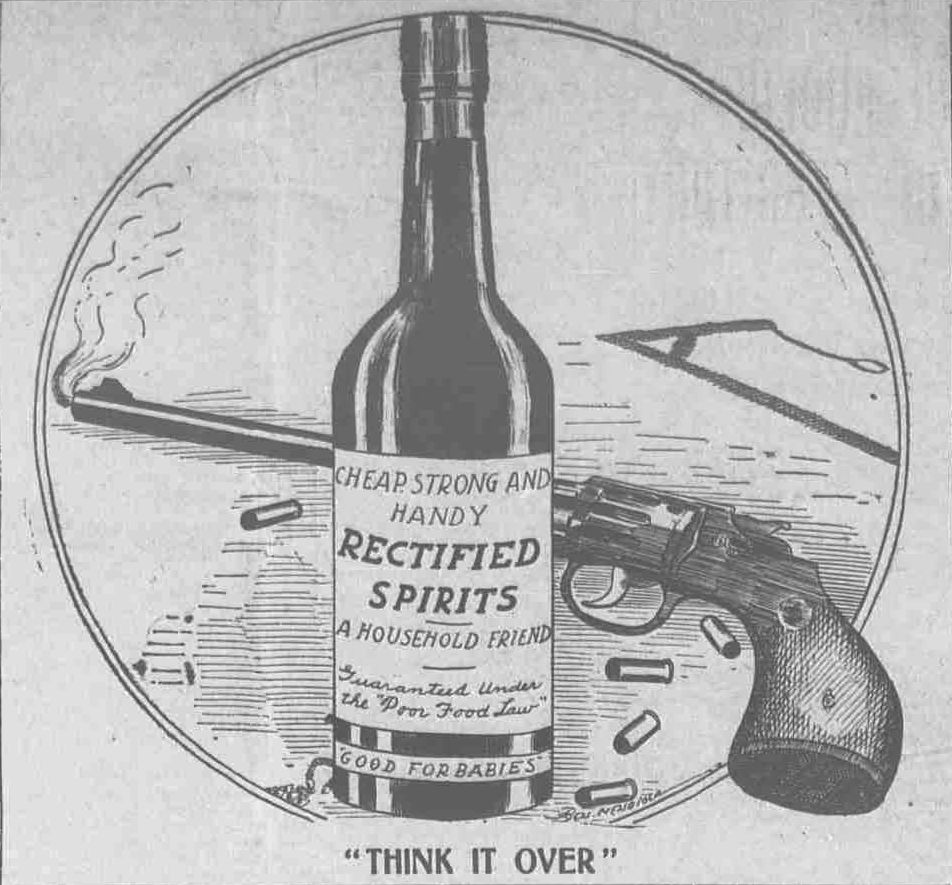

Congress decided that Hawai‘i should hold a special election on Prohibition. The vote occurred in July 1910. The Hawaiian Gazette ran political cartoons to persuade people to vote for prohibition in Hawai‘i.

The newspaper’s editorials and political cartoons portrayed the saloon owners as profiting from the sale of alcohol, or “The White Man Burden,” and the alcohol bringing societal ills to the native Hawaiians. (HDNP)

Kūhiō argued against the bill, asserting that Hawai‘i was guaranteed a large degree of local self-governance. (Curtis) “There are many good people in Hawaii who believe in prohibition but who do not believe that Congress should enact it.,” (Kūhiō, GovInfo)

Ultimately, the Hawai‘i voters voted against prohibition in Hawai‘i. … The Evening Bulletin reported, “The annihilation of the prohibitionists is increasing. If that he possible, in its overwhelming effect as later reports are being received from the other Islands.”

Not one precinct did the pro-Prohibition vote carry on Hawai‘i and the partial returns also indicate this to be a fact on Maui. … The vote indicated anti-prohibitionists’ vote was 7,283 and supporters of prohibition in the Islands tallied 2,185 votes.

“The overwhelming nature of the defeat that has been visited upon the adherents of the [Prohibition] platform in Hawaii, is best indicated by the fact that the anti-prohibitionists polled more votes on Oahu than the prohibitionists polled in the Territory at large.” Evening Bulletin, July 27, 1910)

Pressure in favor of US prohibition grew; in 1917, when O‘ahu was declared a military zone, serving alcohol on the island was banned. Kūhiō viewed the restriction as unfair, since the manufacture and sale of alcohol were still permitted. (GovInfo)

Kūhiō put up a billboard that stated, “You are aware that I am not one who does not touch liquor, neither do I abstain, and I do not want a law which segregates people because they are not white. The days of those activities are over for Hawaii. Kuhio.”

Later, Congress passed the 18th Amendment – the constitutional amendment known as Prohibition – on December 18, 1917. But before it could be added to the Constitution, three-fourths of the states needed to ratify – or approve – the measure. (US House)

While the 18th Amendment prohibited the manufacture, sale and transportation of intoxicating beverages, it did not outlaw the possession or consumption of alcohol in the United States.

The 18th Amendment split the Country; everyone was forced to choose – you were either “dry”, in support of Prohibition, or “wet.” But one thing was clear, Prohibition had little effect on America’s thirst.

Congress imposed prohibition in Hawai‘i in 1918 as a war measure, about a year and a half before the Eighteenth Amendment became effective on the continent. Then, in 1921 in an act supplemental to the National Prohibition Act, the prohibition Act was specifically applied to Hawai‘i, and the territorial courts were given the necessary enforcing jurisdiction. (LRB)

The 18th Amendment would eventually be repealed and overridden by the Twenty-first Amendment in 1933 – it is the only Constitutional amendment to have been fully repealed. (Reagan Library)