While there is only one global ocean, the vast body of water that covers 71 percent of the Earth is geographically divided into distinct named regions. The boundaries between these regions have evolved over time for a variety of historical, cultural, geographical, and scientific reasons.

Historically, there are four named oceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Arctic. However, most countries – including the United States – now recognize the Southern (Antarctic) as the fifth ocean. The Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian are the most commonly known. (NOAA)

The first Europeans to arrive in North America were likely the Norse, traveling west from Greenland, where Erik the Red had founded a settlement around the year 985. In 1001 his son Leif is thought to have explored the northeast coast of what is now Canada and spent at least one winter there.

While Norse sagas suggest that Viking sailors explored the Atlantic coast of North America down as far as the Bahamas, such claims remain unproven. In 1963, however, the ruins of some Norse houses dating from that era were discovered at L’Anse-aux-Meadows in northern Newfoundland, thus supporting at least some of the claims the Norse sagas make.

Portuguese mariners built an Atlantic empire by colonizing the Canary, Cape Verde, and Azores Islands, as well as the island of Madeira. Merchants then used these Atlantic outposts as debarkation points for subsequent journeys.

From these strategic points, Portugal spread its empire down the western coast of Africa to the Congo, along the western coast of India, and eventually to Brazil on the eastern coast of South America.

It also established trading posts in China and Japan. While the Portuguese didn’t rule over an immense landmass, their strategic holdings of islands and coastal ports gave them almost unrivaled control of nautical trade routes and a global empire of trading posts during the 1400s.

The history of Spanish exploration begins with the history of Spain itself. During the fifteenth century, Spain hoped to gain advantage over its rival, Portugal. The marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469 unified Catholic Spain and began the process of building a nation that could compete for worldwide power.

Their goals were to expand Catholicism and to gain a commercial advantage over Portugal. To those ends, Ferdinand and Isabella sponsored extensive Atlantic exploration. Spain’s most famous explorer, Christopher Columbus, was actually from Genoa, Italy.

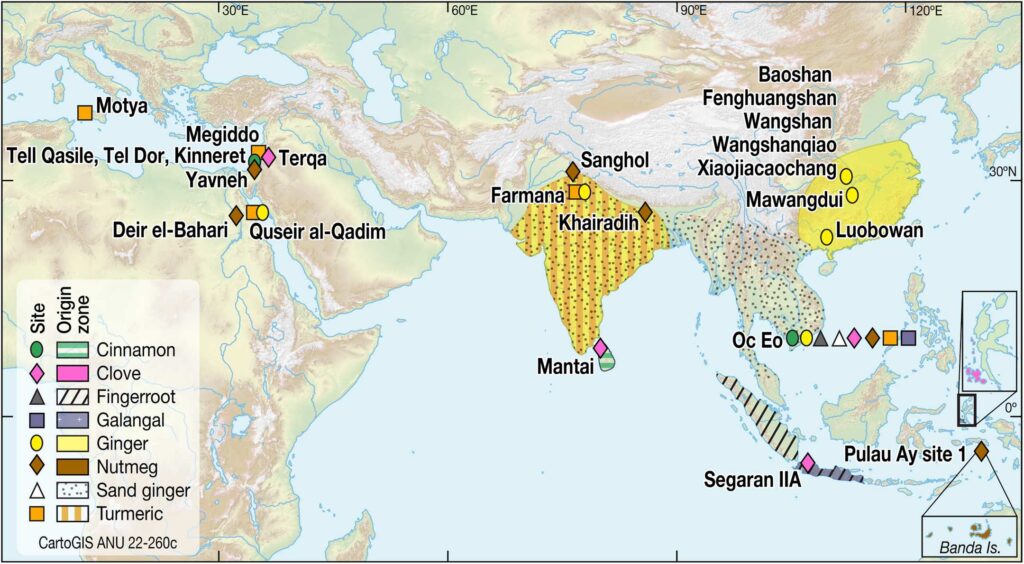

Columbus (who was looking for a new route to India, China, Japan and the ‘Spice Islands’ of Indonesia to bring back cargoes of silk and spices (ginger, turmeric, and cinnamon)) never saw the mainland United States.

Spain’s drive to enlarge its empire led other hopeful conquistadors to push further into the Americas, hoping to replicate the success of Cortés and Pizarro.

The exploits of European explorers had a profound impact both in the Americas and back in Europe. An exchange of ideas, fueled and financed in part by New World commodities, began to connect European nations and, in turn, to touch the parts of the world that Europeans conquered. (Lumen)

“On May 3, 1493, Pope Alexander VI, to prevent future disputes between Spain and Portugal, divided the world by a north-south line (longitude) 100 leagues (300 miles) west of the Cape Verde Islands.”

“In 1494, by the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas, Spain and Portugal agreed to move that line to a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands [in the Atlantic].” (Lloyd)

“Strictly speaking, there was no such thing as ‘the Pacific’ until in 1520-1 Fernao de Magalhãis, better known as Magellan, traversed the huge expanse of waters, which then received its name.” (Spate)

On November 28 1520, Ferdinand Magellan entered the “Sea of the South” (Mar Del Sur, which he later named the Pacific) and thereby opened up to Spain the possibility of an alternative route between Europe and the spices of the Orient.” (Lloyd)

“After Magellan’s daring voyage round South America and across to the Philippines (1519-1521), the magnet of Pacific exploration was Terra Australis Incognita, the great southern continent supposed to lie between the Cape of Good Hope and the Straits of Magellan.” (The Journal; Edwards)

With the conquest of Mexico in 1522, the Spanish further solidified their position in the Western Hemisphere. The ensuing discoveries added to Europe’s knowledge of what was now named America – after the Italian Amerigo Vespucci, who wrote a widely popular account of his voyages to a “New World.”

By 1529, reliable maps of the Atlantic coastline from Labrador to Tierra del Fuego had been drawn up, although it would take more than another century before hope of discovering a “Northwest Passage” to Asia would be completely abandoned. (Alonzo L Hamby)

“Alvaro de Mendana, the Spanish voyager, sailed from Callao in Peru in 1567 and reached the Solomon Islands. It was not until 1595 that he went back, with Pedro Fernanadez de Quiros, found the Marquesas and got as far as the Santa Cruz Islands.” (The Journal; Edwards)

Then, almost 50 years after the death of Christopher Columbus, Manila Galleons finally fulfilled their dream of sailing west to Asia to benefit from the rich Indian Ocean trade.

“The Spanish Galleons were square rigged ships with high superstructures on their sterns. They were obviously designed for running before the wind or at best sailing on a very ‘broad reach.’”

“Because of their apparently limited ability to ‘beat their way to windward’ (sail against the wind), they had to find trade routes where the prevailing winds and sea currents were favorable.” (Lloyd)

Starting in 1565, with the Spanish sailor and friar Andrés de Urdaneta, after discovering the Tornaviaje or return route to Mexico through the Pacific Ocean, Spanish Galleons sailed the Pacific Ocean between Acapulco in Nueva España (New Spain – now Mexico) and Manila in the Philippine islands.

The galleons leaving Manila would make their way back to Acapulco in a four-month long journey. The goods were off-loaded and transported across land to ships on the other Mexican coast at Veracruz, and eventually, sent to European markets and customers eager for these exotic wares. (GuamPedia)

Spain had a long presence in the Pacific Ocean (1521–1898). The Pacific coastline of Nueva España and Peru connected to the Philippines far to the west made the ocean a virtual Spanish Lake.

The “Spanish Lake” united the Pacific Rim (the Americas and Asia) and Basin (Oceania) with the Spanish in the Atlantic. (Buschmann etal)

The great wealth that poured into Spain triggered great interest on the part of the other European powers. With time, emerging maritime nations such as England, drawn in part by Francis Drake’s successful raids on Spanish treasure ships, began to take interest in the New World. (State Department)

The USA is named after an Italian, Amerigo Vespucci (March 9, 1454 – February 22, 1512,) an explorer, financier, navigator and cartographer. He sailed in 1499, seven years after Christopher Columbus first landed in the West Indies.

Columbus found the new world; but Vespucci, by travelling down the coast, came to the realization that it was not India at all, but an entirely new continent.

Later, it was a German clergyman and amateur geographer named Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann, his Alsatian proofreader, who are reported to have first put the name “America” (a feminized Latin version of Vespucci’s first name) on the new land mass (April 25, 1507.)

The name ‘United States of America’ appears to have been used for the first time in the Declaration of Independence (1776.) At least no earlier instance of its use in that precise form has been found. (Burnett)