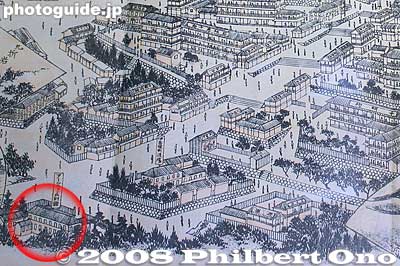

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) unified Japan by defeating his enemies at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. He was made Shōgun in 1603 and set up his headquarters at Edo (modern Tokyo.) The Edo period is also known as the Tokugawa period; Japan was ruled by the Shōgun of the Tokugawa family.

For reasons of national security, from 1639 the Shōgunate ordered that contacts with the outside world be severely limited. Japan’s only regular contacts were with the Dutch, Chinese and Koreans. (British Museum)

Fast forward through a couple centuries of Japan isolation to the mid-1850s … the US hoped Japan would agree to open certain ports so American vessels could begin to trade. In addition to interest in the Japanese market, America needed Japanese ports to replenish coal and supplies for the commercial whaling fleet.

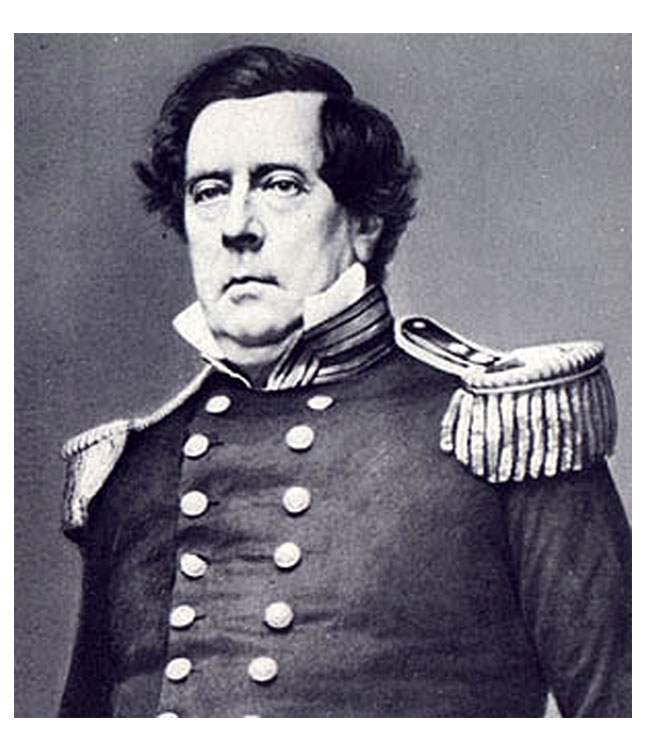

On July 8, 1853, four black ships led by USS Powhatan and commanded by Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, anchored at Edo (Tokyo) Bay. The Japanese thought the ships were “giant dragons puffing smoke” (they had not ever seen steam ships with smoke from their stacks.)

“On that great historic event when the Perry Mission from the United States landed at Uraga (Japan) in 1853, Manjirō served as interpreter. No more suitable person could have been found in all Japan. Manjirō knew the American spirit and desires.”

“Any blunder on his part might have resulted in an international disaster. As it was, the Perry mission was a great success. In spite of the powerful conservatism of Japan’s ruling classes at that time, the country was opened to world-wide commerce.” (Japanese Embassy; Millicent Library)

Let’s look back …

Manjirō was born January 23, 1827 in Nakahama, Kochi Torishima prefecture of Japan during the isolation period. He had a tough life as a young man, the death of his father at age 9 forced him to work to support his family.

By age 14 he was part of a five man fishing boat (Manjirō, Jūsuke, Denzō, Goemon and Toraemon.) During one trip in January 1841, they were caught in a storm and stranded on Torishima Island, off the coast of Japan.

Then, the log book of Captain William Whitfield on the ‘John Howland’ noted (June 27, 1841,) “This day light wind from S. E. Isle in sight at 1 P.M. Sent in two boats to see if there was any turtle, found 5 poor distressed people on the isle, took them off, could not understand anything from them more than that they was hungry.” (Millicent Museum)

After 6-months at sea (arriving in Hawaiʻi,) Whitfield made Manjirō (now called ‘John Mung’ by the crew) an offer – stay in Hawaiʻi and find a ride home, or come with him to America and receive an education. Manjirō continued to the continent with Whitfield, arriving in New Bedford on May 3, 1843 (reportedly, the first Japanese person to live in the US.)

There, he joined the Whitfield household (the Captain had been a bachelor, but shortly after he married) and Manjirō moved with them to the Whitfield home in Fairhaven (as a foster son, not a servant.)

Not accepted at the Whitfield’s church, the family joined the Unitarian Church; a member of the congregation there was the Delano family (a grandson, Franklin Delano Roosevelt later became US president.)

In the following years the young foreigner became well known to the Fairhaven townspeople as Captain Whitfield treated him like a son. He went to his first school ever (the Old Stone School) after being tutored by Miss Allen, a local teacher and neighbor of the captain. He later learned higher level math, navigation and surveying at the Bartlett School.

Then, an opportunity to go to sea came up; the Captain was away, Mrs Whitfield gave her permission for Manjirō to go back to the Pacific and wrote a letter of introduction to a family friend, chaplain of the Seamen’s Bethel in Honolulu, Reverend Samuel C Damon.

He eventually returned to the Island and was repatriated with his friends (Jūsuke had died prior to Manjirō’s return.) After three years at sea, he returned to New Bedford in 1849 (never making it back to his home in Japan – though he yearned to return.)

In October 1849, he got gold fever and rushed to California. After only 70-days in the mines, he earned $600 – about the equivalent of 3-years wages as a whaler. He then headed for Honolulu to encourage his 3 shipmates to return to Japan with him.

They found a ship (‘Sara Boyd’) headed for Shanghai; with the help of Damon and others, they raised enough funds to buy and provision a small boat (‘Adventure’) that they would store on the Sara Boyd and, when they were close to Japan, use it to make it to the islands.

Damon also obtained for Manjiro a US passport and helped him devise a plan to get safely back to his homeland. Next they loaded the Adventure onto a larger American vessel which dropped the small boat off in the waters off present-day Okinawa. (Yamamoto)

On February 3, 1851, 10-years after being shipwrecked, Manjirō, Denzō and Goemon landed on an Okinawan beach (Toraemon did not make the trip, he stayed in Honolulu.) He eventually saw his mother, again.

The Japan leadership recognized the value Manjirō’s fluency in the English language; in addition, he was the only person in Japan who had extensive knowledge of English and American culture at the time. Manjirō was raised to lower rank of samurai due to his usefulness to the Government.

Manjirō began to work for the Japan government; he was given a higher rank of samurai and retainer to the Shōgun, and, as such, he earned the right to carry a family name (he chose Nakahama as his surname, after his hometown.)

He became a teacher at the Tosa School, lecturing on American democracy, on freedom and equality, on the independent spirit, and on his travels on the world’s seas. (Keio)

Manjirō tutored senior officers on the geography and history of the US, and the physical and mental characteristics of Americans. He described American politics and American expectations from Japan and told them how to build and navigate western ships.

With Manjirō’s encouragement, the Shōgunate discarded the 200-years isolation and took the first step toward opening the country in his negotiations with Commodore Perry. It is impossible to measure the service rendered by Manjirō in enabling Japan to accept the Japan-United States Friendship Treaty.

Manjirō’s contributions to the modernization of Japan were invaluable. The Japanese relied heavily on his language skills and knowledge of the West.

America’s 30th president, Calvin Coolidge, later said, “When John Manjirō returned to Japan, it was as if America had sent its first ambassador. Our envoy Perry could enjoy so cordial a reception because John Manjirō had made Japan’s central authorities understand the true face of America.” (Manjirō Society)

The Shōgunate sent a delegation to America in 1860 to exchange ratifications of the Japan-US Commercial Treaty. Manjirō boarded the ‘Kanrin-maru’ as instructor and translator.

The success of the Kanrin-maru voyage across the Pacific impressed the US side with the skill and abilities of the Japanese, and became a basis for the success of later bilateral diplomatic negotiations. (Keio) Manjiro later taught at Kaiser Gakko, forerunner of Toko Imperial University. He died in 1898 at the age of 71.

Manjirō’s contributions to the modernization of Japan were invaluable. He worked hard to establishing good communication between Japanese and Americans.

Both East and West recognized the importance of the friendship and faith Whitfield had in taking the young Manjirō into his home. In 1987, Fairhaven and Tosashimizu, Japan formalized a sister city agreement (Crown Prince Akihito, now Emperor of Japan, visited Fairhaven at that time.) (Fairhaven has a ‘Manjiro Trail,’ highlighting some of the sites, there.)

Gifts of samurai swords were given to the City of Fairhaven and Damon. A short film ‘Friend Ships’ documents the relationship of Manjirō and Whitfield. (Lots of information from Rosenbach Museum, Millicent Museum and Whitfield-Manjiro.)