By the sixteenth century, dozens of bands of people lived in present-day Oregon, with concentrated populations along the Columbia River, in the western valleys, and around coastal estuaries and inlets. (Robbins)

Captain James Cook’s Third Voyage to the Pacific in the 1770s took him to the Pacific Northwest Coast. After Cook was killed in Hawai‘i, his associate George Vancouver continued to explore and chart the Northwest Coast. Commercial traders soon followed, exchanging copper, weapons, liquor, and varied goods for sea otter pelts. (Barbour)

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise in North America. It had an unbroken chain spanning three centuries. During the 1540s on the St. Lawrence River, Jacques Cartier traded European goods, such as axes, cloth, and glass beads, to Indians.

In 1670, King Charles II of England granted a royal charter to create the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), under the governorship of the king’s cousin Prince Rupert of the Rhine. According to the Charter, the HBC received rights to:

“The sole Trade and Commerce of all those Seas, Streights, Bays, Rivers, Lakes, Creeks, and Sounds, in whatsoever Latitude they shall be, that lie within the entrance of the Streights commonly called Hudson’s Streights …”

“together with all the Lands, Countries and Territories, upon the Coasts and Confines of the Seas, Streights, Bays, Lakes, Rivers, Creeks and Sounds, aforesaid, which are not now actually possessed by any of our Subjects, or by the Subjects of any other Christian Prince or State …”

“and that the said Land be from henceforth reckoned and reputed as one of our Plantations or Colonies in America, called Rupert’s Land.”

The Royal Charter of 1670 granted “the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay” exclusive trading rights over the entire Hudson Bay drainage system. It named the area Rupert’s Land in honor of Prince Rupert, cousin to King Charles II and HBC’s first Governor.

Native people provided furs and hides as well as food, equipment, interpreters, guides and protection in exchange for European, Asian, and American manufactures. A primary object of the terrestrial fur trade was beaver, the soft underfur of which was turned into expensive and sought-after beaver hats.

In quest of “soft gold” (beaver, otter, and other lightweight and highly valuable fine furs), which created fortunes large and small for lucky entrepreneurs, the fur hunters’ rosters included capable explorers who expanded the fur trade’s theater of operations and also shed light on western geography. (Barbour)

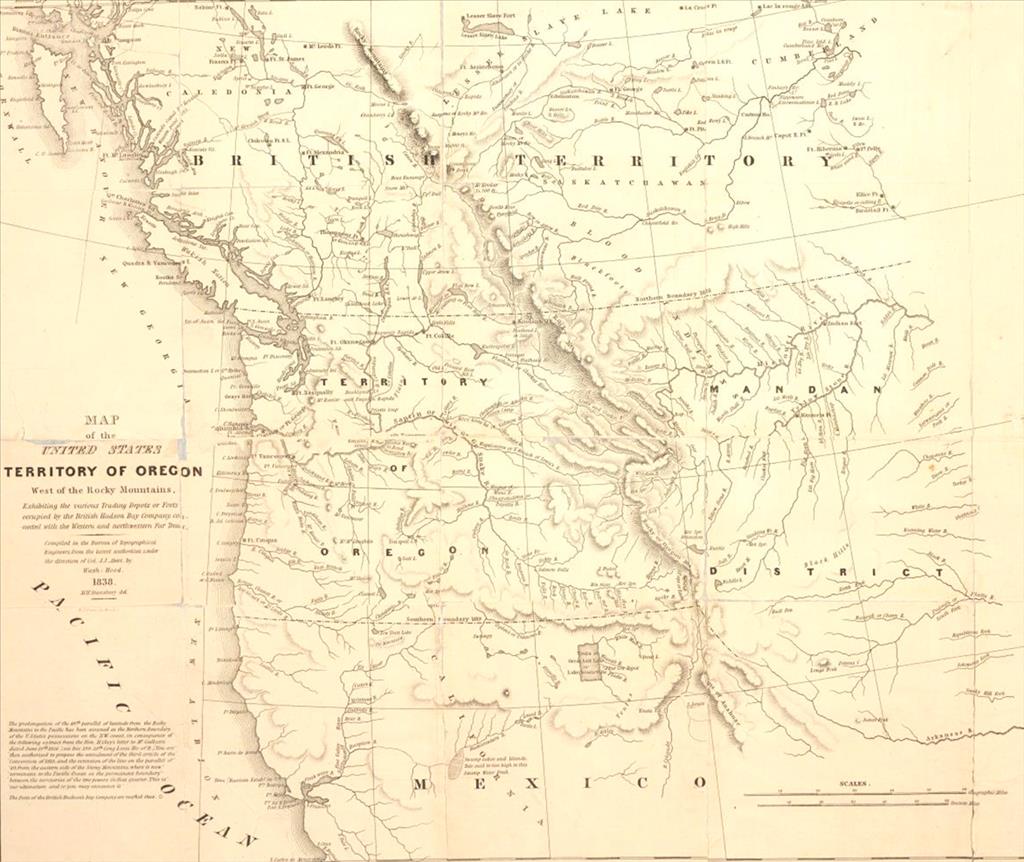

Traders drafted many useful maps and wrote reports meant to help their governments secure geopolitical objectives. Similarly, by providing quarters, protection, and aid to scientists and artists at isolated trading posts, fur traders supported the study of Native Nations and natural history. (Barbour)

Later, the North American fur trade became the earliest global economic enterprise. The maritime fur trade focused on acquiring furs of sea otters, seals and other animals from the Pacific Northwest Coast and Alaska. The furs were to be mostly sold in China in exchange for tea, silks, porcelain and other Chinese goods to be sold in Europe and the US.

Europe’s interest in the North Pacific quickened in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, as Spanish, British, French, Russian, and eventually ships from the United States came into increasing contact with Native people in coastal estuaries. (Robbins)

Following the American Revolution, the new nation needed money and a vital surge in trade. In 1787, a group of Boston merchants decided to send two ships on a desperate mission around Cape Horn and into the Pacific Ocean, to establish new trade with China, settle an outpost on territory claimed by the Spanish and find the legendary Northwest Passage.

By the close of the eighteenth century, the Northwest Coast had become a place with an emerging global economy. (Robbins) Needing supplies in their journey, the traders soon realized they could economically barter for provisions in Hawai‘i; for instance any type of iron, a common nail, chisel or knife, could fetch far more fresh fruit meat and water than a large sum of money would in other ports.

A triangular trade network emerged linking the Pacific Northwest coast, China and the Hawaiian Islands to Britain and the United States (especially New England).

The growing competition on the continent became concerning to the Hudson’s Bay Company and it sought to separate its land. The Oregon Country had not become important to the HBC until 1821, when the HBC merged with the rival North West Company.

The HBC accepted the inevitable loss of most of the region to the Americans and focused on retaining the area bounded by the Columbia River on the south and east, the Pacific Ocean on the west, and the forty-ninth parallel on the north, an area encompassing potential Puget Sound ports and the transportation route provided by the Columbia River.

The HBC developed the idea of clearing the Snake River Basin of beaver in order to create a fur desert, or buffer zone, that would discourage the westward flow of American trappers who began to reach the Northern Rockies in substantial numbers in the 1820s.

The fur desert policy began in response to a territorial dispute over the Oregon Country. The Americans sought control of the entire region. The HBC’s experiences across northern North America had taught a painful lesson: competition depleted beaver trapping grounds and, therefore, profits.

During a visit to the Columbia District to determine its usefulness to the HBC, HBC leader George Simpson carried the idea one step further. He wrote in an 1824 journal entry:

“If properly managed no question exists that it would yield handsome profits as we have convincing proof that the country is a rich preserve of Beaver and which for political reasons we should endeavor to destroy as fast as possible.” The fur desert policy had begun.

To protect its interest, between then and 1841, the Hudson’s Bay Company carried out what is known as the fur desert policy – a strategy of clearing the basin of beaver to keep encroaching Americans from coming west of the Continental Divide. (Ott)

The HBC assembled varied groups (brigades) of trappers to go into the Snake Country to trap in the region. Each chief trader who led the Snake Country expeditions during the most important years, from 1823 to 1841, worked under the pressure of the HBC’s expectations of good pelt returns, the exclusion of Americans from the region, and the trapper’s return in time to meet the annual supply ship.

During the critical years when the policy was in place, the HBC took approximately 35,000 beaver out of the region. The 1823 – 1824 brigade alone yielded 4,500 beaver. By 1834, the average annual yield was down to 665 beaver. (Ott)

If there remained any doubt that the trappers intended to “ruin” the rivers and streams, the journals clarify their goal for the area. At the Owhyhee River in 1826, Ogden added this comment to the end of his daily entry: “This day 11 Beaver 1 Otter we have now ruined this quarter we may prepare to Start.”

Two weeks later, at the Burnt River, Ogden wrote George Simpson: “the South side of the South branch of the Columbia [the Snake River] has been examined and now ascertained to be destitute of Beaver.” (Ott)

Through their use of efficient Snake Country trapping brigades, the HBC nearly eradicated beaver in the region and, in the process, redefined the physical space in which people would live.

“From the start, there is a sense that trapping exceeded the resilience of the local beaver population. As time passed, the ransacking done by the trappers produced a widespread effect. The effects of American and Indian trapping also contributed to the success of the fur desert policy.” (Ott)