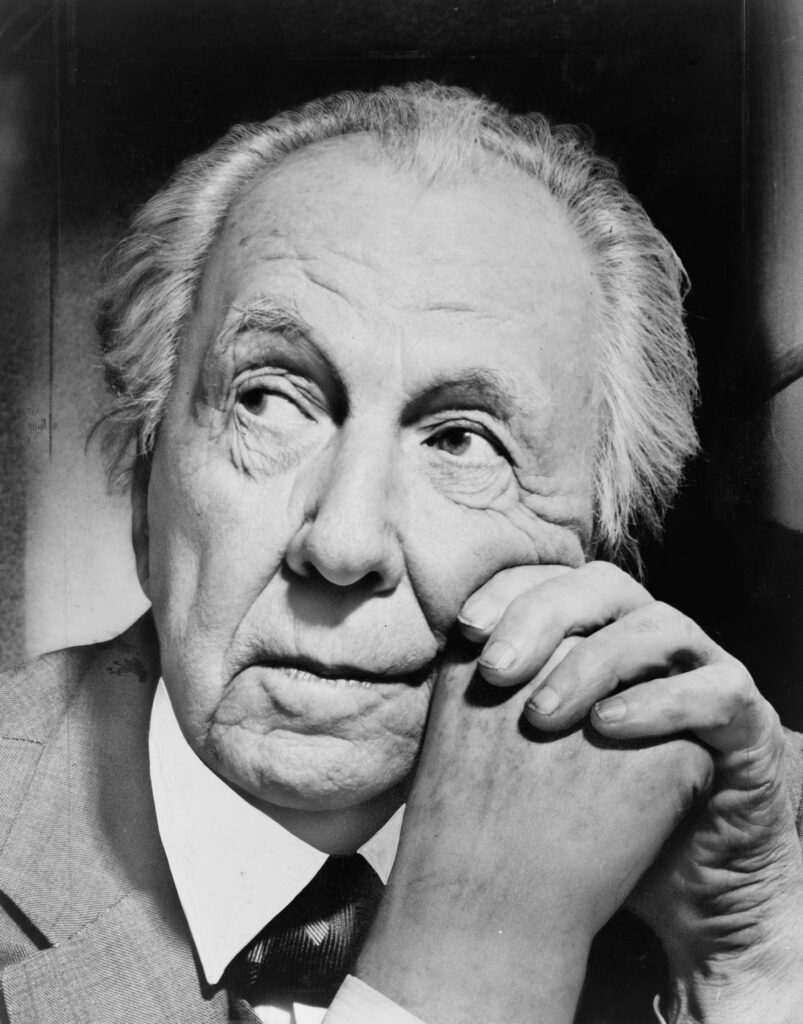

“The mission of an architect is to help people understand how to make life more beautiful, the world a better one for living in, and to give reason, rhyme, and meaning to life.” (Frank Lloyd Wright, 1957)

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in Richland Center, Wisconsin, on June 8, 1867, the son of William Carey Wright, a preacher and a musician, and Anna Lloyd Jones, a teacher whose large Welsh family had settled the valley area near Spring Green, Wisconsin.

His early childhood was nomadic as his father traveled from one ministry position to another in Rhode Island, Iowa, and Massachusetts, before settling in Madison, Wis., in 1878.

Wright’s parents divorced in 1885, making already challenging financial circumstances even more challenging. To help support the family, 18-year-old Frank Lloyd Wright worked for the dean of the University of Wisconsin’s department of engineering while also studying at the university.

He knew he wanted to be an architect. In 1887, he left Madison for Chicago, where he found work with two different firms before being hired by the prestigious partnership of Adler and Sullivan, working directly under Louis Sullivan for six years.

In 1911, he began construction of Taliesin near Spring Green as his home and refuge. There he continued his architectural practice and over the next several years received two important public commissions: the first in 1913 for an entertainment center called Midway Gardens in Chicago; the second, in 1916, for the new Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan.

Wright always aspired to provide his client with environments that were not only functional but also “eloquent and humane.” Perhaps uniquely among the great architects, Wright pursued an architecture for everyman rather than every man for one architecture through the careful use of standardization to achieve accessible tailoring options to for his clients.

Over the course of his 70-year career, Wright became one of the most prolific, unorthodox and controversial masters of 20th-century architecture, creating no less than twelve of the Architectural Record’s hundred most important buildings of the century.

Realizing the first truly American architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses, offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels and museums stand as testament to someone whose unwavering belief in his own convictions changed both his profession and his country.

Designing 1,114 architectural works of all types – 532 of which were realized – he created some of the most innovative spaces in the United States. With a career that spanned seven decades before his death in 1959, Wright’s visionary work cemented his place as the American Institute of Architects’ “greatest American architect of all time.” (Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation)

Two of his designs are in Hawai‘i; one, an unbuilt plan done in 1954, originally conceived for the Cornwell Family in Pennsylvania, was constructed in 1995 in Waimea on Hawai‘i Island.

It envisioned to be part of master-planned community that would include many unbuilt Wright designs within a 450 acre plot on Hawai‘i Island. The “Hawai‘i Collection” development never got off the ground.

The other Hawai‘i Frank Lloyd Wright design was also an unbuilt design for a prior client of Wright’s that he designed in 1949. This was originally a home called Crownfield; but the couple who commissioned the home never built it.

When Wright was approached in 1952 to design a home for the cliffs of Mexico’s Acapulco Bay, he began with the Crownfield plans, and added a covered terrace and lower level. Unfortunately, the plans were shelved once again.

Again, after further modification in 1957, Crownfield almost became the home of Marilyn Monroe and her husband Arthur Miller. Monroe and Miller separated the next year and the home was never built.

For several decades the plans for the Crownfield House were archived in Taliesin West, Wright’s former winter camp near Scottsdale, Arizona, which became the headquarters for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

There they remained until, in 1992, owners of the Ted Robinson-designed Waikapu Valley Country Club looked for a Wright design for the golf clubhouse.

The Crownfield House’s various reincarnations were reworked and expanded yet again . The finished building, now called the King Kamehameha Golf Clubhouse, is 74,788 square feet. The concrete and steel building was completed in 1993 and is split into three levels with two-thirds of the structure underground. It is the largest golf clubhouse on Maui.

Many of the interior touches reiterate other famous Wright design triumphs. The focus of the main banquet room is a 32-foot diameter dome with a convex chandelier made of one-and-a-half-inch acrylic tubing that echoes the concave chandelier in the Johnson Wax Building’s executive suite (1944) in Racine, Wisconsin.

The art glass on the front double doors was adapted from the Johnson Wax Building as well. The etched design on the glass of the main stairwell’s koa railing, the foyer’s six-foot-diameter art glass window, and the brass elevator doors can all be traced to Wright’s Avery Coonley House (1907) in Riverside, Illinois.

The ten-foot diameter art glass in the foyer ceiling was translated from a 1957 woven living room carpet at Taliesin West and the skylight above the main stair recalls the curved ransom over the Susan Lawrence Dana House’s entrance (1902) in Springfield, Illinois.

Six years after it was built the country club shut down during an economic downturn. The property was pretty much neglected and abandoned. However, the clubhouse stayed open and was used for special events. In 2004 a buyer bought the place and refurbished it. It was reopened in 2006 as the King Kamehameha Golf Clubhouse. (Maui 24/7, King Kamehameha Golf Course)