“Where the sunbeams had slept placidly on an unbroken surface of azure, they were now reflected hither and thither by the black sides of canoes, the flashing of outriggers, the sheen of polished metal, the scarlet and yellow of innumerable feather cloaks …”

“… the glittering of oars amid the spray-rain, the gleaming of dusky bodies, and the forward leap of the high prows, whose painted eyes seemed to glow with the fire of life.”

“And in advance was the famous double war canoe Peleleu, the rowers straining at the oars, and the kahili-bearers and warriors standing around the mighty chief who was destined to make Hawaii a nation”

“On they came, nearing the flat beach of Waikiki, where unless Kalanikapule opposed, they could enter the coral reef and land without impediment.”

“But Kalanikapule chose to meet his rival in the heart of the country among the palis, rather than on the level ground; so, though from Leahi you could have seen the moving of dark masses of men among the forests of the southern side of the island, there was no sign on the beach of opposition to the landing of the Hawaiian troops.” (Gowen)

“Since koa is indigenous plant, i.e. one ‘native’ to Hawaii , it grew ‘wild’ in large forest, and Hawaiians did not propagate it. … The prime importance of koa was in the making of canoes, not only the single kinds, kaukahi, but even double kinds, kaulua, which consisted of two canoes lashed together in a special way.”

“Before making a canoe, the Hawaiians employed a kahuna, or priest, to offer prayers and sacrifices to Ku, the long-bearded god of canoe makers, that the work should be successful. Then the kahuna aided the men in selecting a suitable tree in the forest. … The part made from the koa trunk was the wa‘a.” (Krauss)

Waʻa Peleleu, or simply Peleleu, were long canoes or long voyages were usually 50 feet long, but some were 100 and even 150 feet long. Such canoes were 1 to 2 feet wide and carved from a single log. (Krauss)

Canoes evolved to meet new demands; the sail had become the primary power mode – those also evolved. “In the early 1790s the watch aboard a foreign ship sailing off O‘ahu saw a vessel approaching which, by the cut of its sails, appeared to be European.”

“But as it drew near and passed by it was seen to be a Hawaiian canoe with sails cut to European shape. This was the fore-and-aft spritsail. It was a simple modification, changing the ancient triangular sail to a four-sided shape.”

“Also, from the base of the mast the foot of the sail ran horizontally aft to the clew (bottom trailing edge) where the sheet (controlling line) connected to it. In larger canoes the foot was laced to a boom. This rig quickly became the standard for most Hawaiian sailing canoes.”

“On some of the largest double canoes a sail of about the same shape was used, not with a sprit, but gaff-rigged, the head (top of the sail) laced to a spar which was raised or lowered by halyards, and the entire foot of the sail laced to a boom.” (Herb Kane)

“Kamehameha’s drive to bring all the islands under the rule of Hawai’i Island required much more than the hit and run raids of earlier disputes.”

“Keeping armies in the field required great numbers of huge canoes, not only for invasion but also for keeping the army supplied, which meant canoes capable of returning to Hawai‘i Island, sailed (not paddled) short-handed and against the prevailing wind, for supplies and reinforcements.”

The peleleu class war canoes were invented for that purpose. “These were sailing vessels with deep hulls, some armed with swivel guns, carrying fore-and-aft sail rigs, either as spritsails or gaff-rigged and capable of sailing upwind.” (Herb Kane)

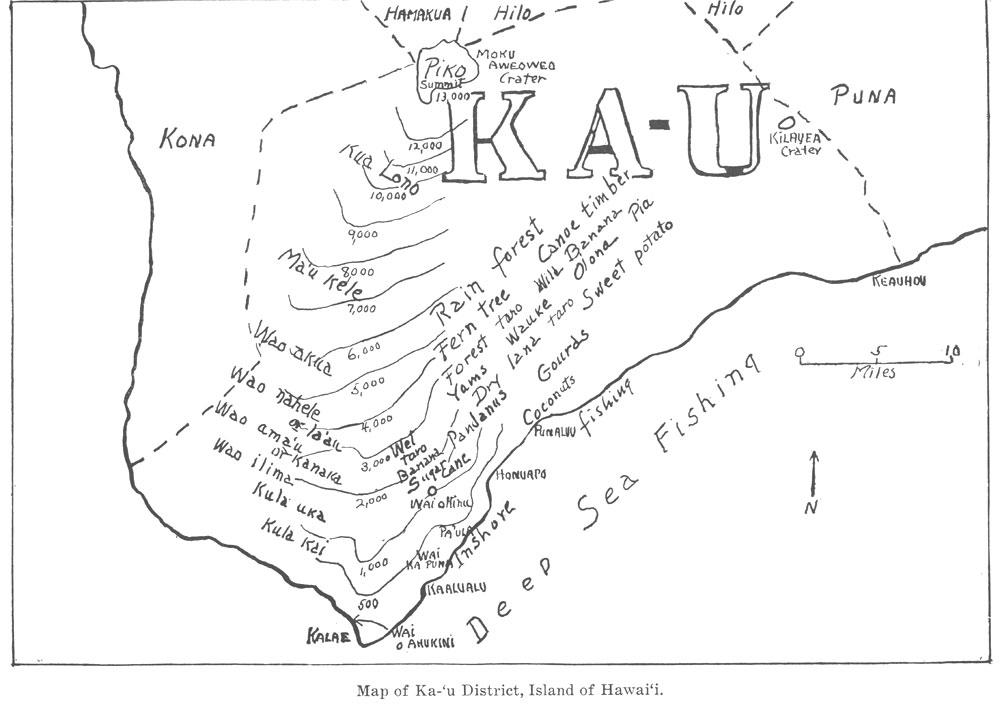

“The peleleu were a fleet of very large war-canoes which Kamehameha I had made from koa trees felled in the forests back of Hilo, Hawaii. Their construction was begun about the year 1796.”

“In spite of the fact that the Hawaiian historian, Malo, speaks of the peleleu with a certain pride and enthusiasm, they are to be regarded rather as monstrosities, not belonging fully to the Hawaiian on whose soil they were made, nor to the white men who, no doubt, lent a hand and had a voice in their making and planning.” (Malo)

“So great was the size of these canoes and such their depth from the gunwale down, that flooring had to be made on which the paddlemen might stand, or rest their feet while sitting on the usual paddlers’ seats.” (Emerson in Mills)

“They were excellent craft and carried a great deal of freight. The after part of these crafts were similar in construction to an ordinary vessel (i. e. was decked over).”

“It was principally by means of such craft as these that Kamehameha succeeded in transporting his forces to Oahu when he went to take possession of that part of his dominion when he was making his conquests.” (Malo)

“The large, wide and deep peleleu canoes, however, quickly became obsolete. In comparison with standard double canoes, they were unwieldly, labor intensive, and impractical for common use”. (Mills)