Kaho‘olawe is the smallest of the eight Main Hawaiian Islands, 11-miles long and 7-miles wide (approximately 28,800-acres,) rising to a height of 1,477-feet. It is seven miles southwest of Maui.

Archaeological evidence suggests human habitation began as early as 1000 AD; it is known as a navigational and religious center, as well as the site of an adze quarry. Subsistence farmers and fishers formerly populated Kaho‘olawe.

Interestingly, the entire island of Kaho‘olawe is part of an ahupua‘a from the Maui district of Honua‘ula. The island is divided into ʻili (smaller land units within ahupua‘a.)

Kekāuluohi “made Kahoʻolawe and Lānaʻi penal settlements for law breakers to punish them for such crimes as rebellion, theft, divorce, breaking marriage vows, murder and prostitution.” (Kamakau)

The first prisoners exiled to Kahoʻolawe were a Hawaiian man convicted of theft, and a woman accused of prostitution, both of whom were sent to the island on June 13, 1826. (Reeve; KIRC)

“The village is a collection of eight huts, and an unfinished adobe church. The chief has three large canoes for his use. In passing over the island, the walking had been found very tedious; for they sunk ankle-deep at each step.”

“The whole south part is covered with a light soil, composed of decomposed lava; and is destitute of vegetation, except a few stunted shrubs.”

“On the northern side of the island, there is a better soil, of a reddish colour, which is in places susceptible of cultivation. Many tracks of wild hogs were seen, but only one of the animals was met with.”

“The only article produced on the island is the sweet-potato, and but a small quantity of these. All the inhabitants are convicts, and receive their food from Maui: their number at present is about fifteen.”

“Besides this little cluster of convicts’ huts, there are one or two houses on the north end, inhabited by old women. Some of the convicts are allowed to visit the other islands, but not to remain.” (Wilkes, 1845)

The “Act of Grace” of Kamehameha III, in commemoration of the restoration of the flag by Admiral Thomas July 31, 1843, let “all prisoners of every description” committed for offenses during the period of cession “from Hawaiʻi to Niʻihau be immediately discharged,” royal clemency was apparently extended to include prisoners of earlier conviction. (Thrum)

Located in the “rain shadow” of Maui’s Haleakala, rainfall has been in short supply on Kaho‘olawe. Historically, a “cloud bridge” connected the island to the slopes of Haleakalā. The Naulu winds brought the Naulu rains that are associated with Kaho‘olawe (a heavy mist and shower of fine rain that would cover the island.)

In 1858 the first lease of Kahoʻolawe was sold at public auction. Plans were made to turn the Island into a sheep ranch. From then until World War II, Kahoʻolawe was effectively used as a livestock ranch.

A constant theme from 1858 on was elimination of wild animals that were destroying the vegetation. At first wild dogs, hogs, and goats were the predators. By the end of the 19th century, grazing of cattle, goats and sheep were the destroyers. (King; KIRC)

“The Island of Kahoolawe consists of one government land, at present under an expiring lease held by Mr Eben P Low, that runs out on January 1, 1913. This lease was formerly held by Mr. CC Conradt, now of Pukoʻo, Molokai, and was transferred by him to Mr Low a few years since.”

“Prior to that time the island had passed through many hands. It has been used continuously for many years for the grazing of cattle, and especially of sheep.” (Hawaiian Forester, 1910)

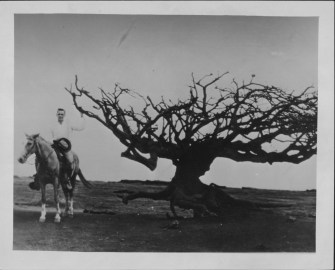

“A great part of the time it has been badly overstocked, a condition which has resulted in the destruction of the original cover of vegetation, followed by erosion and the loss of large quantities of valuable soil, much of which has literally been blown away to sea by the strong trade wind.”

“As the result of long years of overstocking, Kahoolawe has become locally a name practically synonymous with desolation and waste. The object of declaring the island a forest reserve is to put it in a position where, upon the expiration of the existing lease, effective steps could be taken toward its reclamation.” (Hawaiian Forester, 1910)

The Island was a forest reserve from August 25, 1910 to April 20, 1918. But, it was determined, “(I)t would be a foolish waste of money to attempt to reforest the bare top of the island; that for the good of the island the remaining sheep and goats should be exterminated or entirely removed”. (Hawaiian Forester, 1918)

“(T)here is a vast area of pili grass valuable for fattening cattle for the market and tons of algaroba beans on the island going to waste annually; that under a carefully prepared lease of the island with due restrictions and limitations good use could be made of these and at the same time the goats could be required to be exterminated.” (Hawaiian Forester, 1918)

While ranching restarted with a lease to Kahoʻolawe Ranch, it was a later use that further impacted the Island. Military practice bombing of the island is reported to have begun as early as 1920. (Lewis; american-edu)

Then, in May 1941, Kahoʻolawe Ranch signed a sublease for a portion of the island with the US Navy for $1 per year to 1952, when the Ranch’s lease expired. Seven months later, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and initiation of martial law, the military took over the whole island and ranching operations ended. (PKO)

Bombing of the island continued to 1990. Then, in 1992, the State of Hawai‘i designated Kahoʻolawe as a natural and cultural reserve, “to be used exclusively for the preservation and practice of all rights customarily and traditionally exercised by Native Hawaiians for cultural, spiritual, and subsistence purposes.” (KIRC)

In 1993, Congress voted to end military use of the Island and authorized $400-million for ordnance removal. In 2004, The Navy ended the Kahoʻolawe UXO Clearance Project.

At its completion, approximately 75% of the island was surface cleared of unexploded ordnance (UXO). Of this area, 10% of the island, or 2,647 acres, was additionally cleared to the depth of four feet. Twenty-five percent, or 6,692 acres, was not cleared and unescorted access to these areas remains unsafe. (KIRC)

With the help of hard work by volunteers and Kahoolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) staff, the island is healing and recovering. Kahoʻolawe is being planted with native species that include trees, shrubs, vines, grasses and herbs.

Every year, the planting season begins with a ceremony that consists of appropriate protocols, chants, and hoʻokupu given at a series of rain koʻa shrines that were built in 1997.

The shrines link ʻUlupalakua on Maui to Luamakika, located at the summit of Kahoʻolawe, seeking to call back the cloud bridge and the rains that come with it.

I was fortunate to have served on the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) for 4½-years and had the opportunity to visit and stay overnight on Kaho‘olawe; the experiences were memorable and rewarding.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

Follow Peter T Young on LinkedIn

Follow Peter T Young on Blogger