With its panoramic view from Koko Head to Waiʻanae, the summit of Diamond Head was an ideal site for the coastal defense of O‘ahu. In 1904, Diamond Head was purchased by the Federal government and designated for military use.

In 1906, Secretary of War William H Taft convened the National Coast Defense Board (Taft Board) “to consider and report upon the coast defenses of the United States and the insular possessions (including Hawai‘i.)” They recommended a system of Coast Artillery batteries to protect Pearl Harbor and Honolulu.

Fortification of Diamond Head began in 1908 with the construction of gun emplacements and an entry tunnel through the north wall of the crater from Fort Ruger known as the Mule Tunnel.

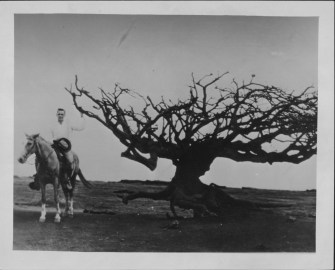

Originally, the tunnel was 5-feet wide and 7-feet high which is what was required for mules. Mules were used primarily to pull narrow gauge rail cars loaded with material in and out of the crater and to the various construction points.

Fort Ruger Military Reservation was established at Diamond Head (Leʻahi) in 1906. The Reservation was named in honor of Major General Thomas H. Ruger, who served from 1871 to 1876 as the superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The trail to the Diamond Head summit was built in 1908 as part of the US Army Coastal Artillery defense system. Entering the crater from Fort Ruger, through the Mule Tunnel, the trail scaled the steep interior western slopes of the crater to the summit.

The dirt trail with numerous switchbacks was designed for mule and foot traffic. The mules hauled materials on this trail for the construction of Fire Control Station Diamond Head located at the summit. Other materials were hoisted from the crater floor by a winch and cable to a midway point along the trail. (DLNR)

In about 1910, there was a narrow gauge railway running from the mule tunnel across the center of the crater

Between 1909-1921, the Hawaiian Coast Artillery Command had its headquarters at Fort Ruger and defenses included artillery regiments stationed at Fort Armstrong, Fort Barrette, Fort DeRussy, Diamond Head, Fort Kamehameha, Kuwa‘aohe Military Reservation (Fort Hase – later known as Marine Corps Base Hawaiʻi) and Fort Weaver.

The forts and battery emplacements were dispersed for concealment and to insure that a projectile striking one would not thereby endanger a neighbor.

The fort included Battery Harlow (1910-1943 – northern exterior;) Battery Hulings (1915-1925- (tunnels through crater wall;) Battery Dodge (1915-1925 – tunnels through east crater wall;) Battery Mills (1916-1925 – on Black Point;) Battery Birkhimer (1916-1943 – mostly below ground inside the crater;) Battery Granger Adams (1935-1946 – on Black Point (replaced Battery Mills;)) Battery 407 (1944 – tunnels through south crater wall;) and Battery Ruger (1937-1943).

In 1922, Mule Tunnel was enlarged to 15 feet wide by 14 feet high. A Fire Control Switchboard that had been in a shed outside the tunnel was moved into a room carved into the wall about 100 feet from the outside end. (Its name later changed to the Kapahulu Tunnel.)

The headquarters of the Harbor Defenses of Honolulu came to Fort Ruger in January 1927. In 1932 work began on a bombproof Harbor Defense Command Post (HDCP or “H” Station) built into the Kapahulu Tunnel.

During the widening of the tunnel, a larger cavern was cut into the wall of the tunnel at the downhill end, creating rooms for a Harbor Defense Command Post.

The new complex of eight rooms included the old fire control switchboard room and became the Harbor Defense Command Post. (Those rooms are now used by the Hawaii Red Cross as storage.)

In 1932 the tunnel was enlarged again, to 17 feet high to allow truck traffic. During the widening a larger cavern was cut into the wall of the tunnel at the downhill end, creating rooms for a Harbor Defense Command Post.

The Kahala Tunnel was built in the 1940s and is the public entrance today. (The Kapahulu Tunnel is used only when the Kahala Tunnel is closed for repairs or problems.)

In January 1950 Fort Ruger became the headquarters of the Hawaii National Guard. In 1955 most of the Fort Ruger reservation was turned over to Hawaii with the U.S. Army retaining the parade and Palm Circle until 1974 and the Cannon Club (officers’ club) until 1997.

The fort’s barracks area became the University of Hawaii’s Kapiʻolani Community College. (Lots of information is from DiamondHeadHike.)

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

Follow Peter T Young on LinkedIn

Follow Peter T Young on Blogger