“Resolved, That, in consideration of the long and meritorious services of Capt John Paty, as a ship master out of Honolulu, and the valuable assistance rendered by him in the furtherance of commercial intercourse between the Hawaiian Islands and adjacent ports in foreign countries, as evidenced by the accomplishment of his one hundredth passage across the Pacific,”

“We, American residents and others, in Honolulu, in meeting assembled deem him entitled to be hailed as the Commodore of the Merchant Marine, at the Sandwich Islands, and as such to fly some ensign, emblematical of the rank thus bestowed upon him … on his arrival from San Francisco, and that on its presentation, he shall be saluted with the customary salute of 13 guns.” (The Friend, November 1, 1860)

“Capt. Paty is a native of good old Plymouth, Mass., and for aught we know, the blood of the master of the May Flower runs in his veins. (He) is one of those Cape Cod boys, of whom it has been eloquently said, ‘They leap from the cradle to the shrouds without holding on to their mother’s apron strings.’” (The Friend, November 1, 1860)

They presented him with a commodore’s broad pennant of blue silk, with the figure 100, encircled by ten white stars representing the ten Hawaiian Islands, and with a chronometer; tokens of the community’s appreciation of his years of reliable service. (Hackler)

Let’s look back.

John Paty was born February 22, 1807 in Plymouth, Massachusetts. His father was a seaman and his mother came of a seafaring family; his father died when John as 7 and his mother, when he was 11.

His first sea-voyage was made in 1821 (at the age of 15,) in the Brig Gov. Winslow, from Boston to Amsterdam with his uncle, Captain Ephraim Paty. He quickly learned the rigors of life aboard ship, for his relative showed him no favors.

Looking back on his early days at sea, “But when I got on board ship with a hard old shell-back, I found the contrast very great, and my feelings were such, at times, as to induce me to commit almost any deed of violence for the sake of revenge. At other times I wished that I had never been born.” (Paty; Day)

“His earlier voyages were to the Mediterranean and West Indies, and, it is said, young as he then was, the owners for whom he sailed reposed so much Confidence in his integrity, good judgment, and nautical skill, that they were in the habit of giving him no instructions other than the general and verbal one, to act according to his own discretion.” (Daily Alta California, February 3, 1869)

He was married in the year 1831 (to his childhood sweetheart, Mary Ann Jefferson of Salem, Massachusetts;) they made their home in Plymouth. Two years later John’s younger brother Henry returned from the Sandwich Islands. He persuaded John to buy a part interest in the brig Avon and sail in it to Hawai’i.

In 1834, John and Mary Ann sailed for the Sandwich Islands, in the brig Avon, of which he was master and part owner, accompanied by his wife and brother, and arrived at Honolulu in June of that year. (They had three children while in Hawaiʻi, John Henry Paty (1840,) Mary Francesca Paty (1844) and Emma Theodora Paty (1850.)

He took various voyages back and forth to the continent; on one, he landed in San Francisco in December, 1837 (it was part of Mexico at the time.) The only buildings in San Francisco were an unfinished adobe belonging to Capt. Wm. Richardson (an Englishman,) and a board shanty near it owned by Jacob P. Leese (an American.) These two were the only foreign residents there. (Day; Hesperian)

“Since that time, with the exception of one or two voyages to Atlantic ports previous to 1839, he had been constantly employed in the Pacific, and, principally, between the Hawaiian Islands and parts of Mexico and California.” (Daily Alta California, February 3, 1869)

In 1857 King Kamehameha IV asked Paty to take the Manuokawai on a voyage of exploration, in the course of which he took possession of Laysan, Necker, Gardener’s Islands and Lysiansky Islands for the Hawaiian Kingdom. He also corrected old charts, “… a considerable portion of my time has been consumed by calms and looking for banks and islands which do not exist, or are erroneously marked ….” (Paty; Hackler)

After 168 crossings, in command of the Don Quixote, the Frances Palmer, the Yankee, the Speedwell, the Young Hector, and the Comet, Paty could assert with pride that he never lost a passenger or a seaman, never lost a ship, and never had a serious accident at sea. (Hackler)

“Old salt,” Capt. John Paty, so long and favorably known throughout the Pacific as one of the most obliging and successful shipmasters that ever commanded a vessel … He has been employed in almost every kind of sea service, in nearly every part of the world, and has universally given most unqualified satisfaction.” (Polynesian, October 13, 1860)

“Those sailing with him always considered themselves fortunate and secure; and his quiet, amiable disposition, unalloyed good-nature, and uniform courtesy and kindness of manner, made it a pleasure to be a passenger and guest on board the vessel where he was master and host.” (Daily Alta California, February 3, 1869)

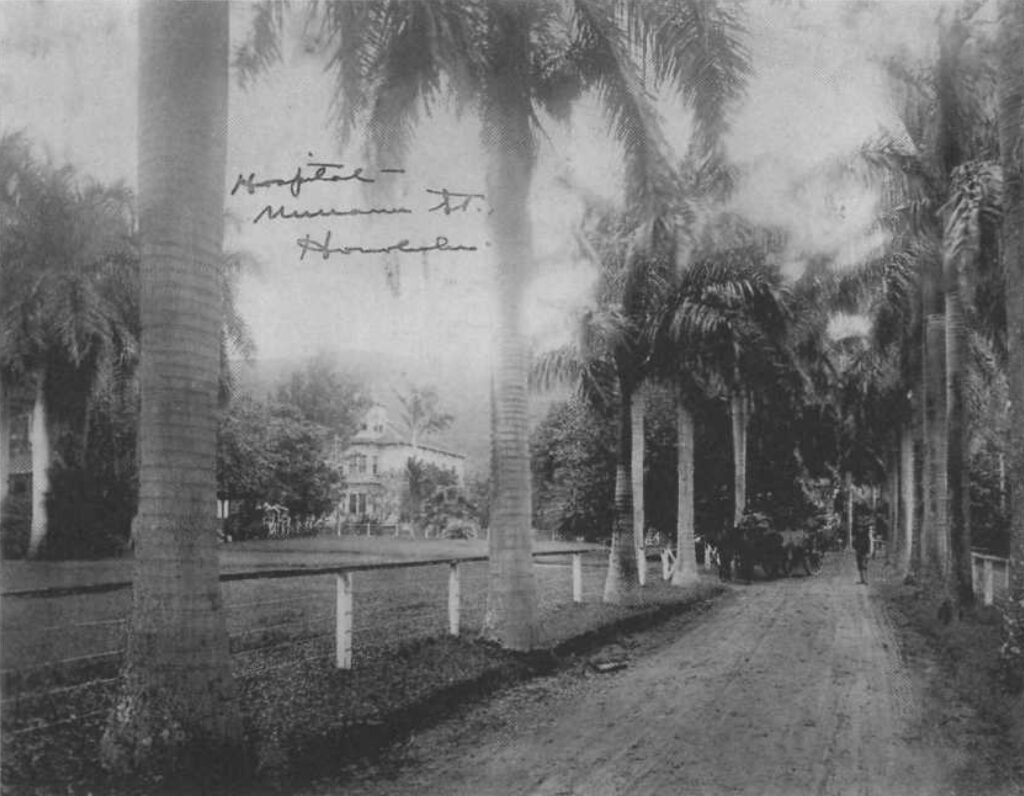

Paty had his home, ‘Buena Vista,’ in Nuʻuanu (on the east side of Nuʻuanu Avenue at Wyllie Street). (That site is now covered by the Nuʻuanu-Pali Highway interchange.)

John Paty continued to ply the Pacific until four months before his death from cancer, on November 11, 1868.