Within ten years after Captain Cook’s 1778 contact with Hawai‘i, the islands became a favorite port of call in the trade with China. The fur traders and merchant ships crossing the Pacific needed to replenish food supplies and water.

The maritime fur trade focused on acquiring furs of sea otters, seals and other animals from the Pacific Northwest Coast and Alaska. The furs were mostly sold in China in exchange for tea, silks, porcelain and other Chinese goods, which were then sold in Europe and the United States.

Needing supplies in their journey, the traders soon realized they could economically barter for provisions in Hawai‘i; for instance any type of iron, a common nail, chisel or knife could fetch far more fresh fruit meat and water than a large sum of money would in other ports.

A triangular trade network emerged linking the Pacific Northwest coast, China and the Hawaiian Islands to Britain and the United States (especially New England).

Foreign vessels had long recognized the ability of the Hawaiian Islands to provision their ships with food (meat and vegetables,) water, salt and firewood.

Salt was Hawaiʻi’s first export, carried by some of the early ships in the fur trade back to the Pacific Northwest for curing furs. Another early market was provided by the Russian settlements in Alaska.

Salt Exports ran to around 2,000 to 3,000 barrels a year in the 1830s, reached 15,000-barrels in 1847 and thereafter declined gradually until exports ceased in the 1880s. (Hitch)

But salt in Hawaiʻi was not just for export.

Salt “has ever been an essential article with the Sandwich Islanders, who eat it very freely with their food, and use much in preserving their fish.” (Ellis, 1826)

During Cook’s visits to the Islands, King’s journal noted “the great quantity of salt they eat with their flesh and fish. … almost every native of these islands carried about with him, either in his calibash, or wrapped up in a piece of cloth, and tied about his waist, a small piece of raw pork, highly salted, which they considered as a great delicacy, and used now and then to taste of.”

“Their fish they salt, and preserve in gourd-shells; not, as we at first imagined, for the purpose of providing against any temporary scarcity, but from the preference they give to salted meats.” (King, 1779)

“(T)he Sandwich Islanders eat (salt) very freely with their food, and use much in preserving their fish. … The surplus … they dispose of to vessels touching at the islands, or export to the Russian settlements on the north-west coast of America, where it is in great demand for curing fish, &c.” (Ellis, 1826)

Early salt production was made by natural evaporation of seawater in tidal ponds. (Hitch) “Amongst their arts, we must not forget that of making salt, with which we were amply supplied, during our stay at these islands, and which was perfectly good of its kind.”

“Their salt pans are made of earth, lined with clay; being generally six or eight feet square, and about eight inches deep. They are raised upon a bank of stones near the high water mark, from whence the salt water is conducted to the foot of them, in small trenches, out of which they are filled, and the sun quickly performs the necessary process of evaporation.” (King, 1779)

The Hawaiians “manufacture large quantities of salt, by evaporating the sea water. We saw a number of their pans, in the disposition of which they display great ingenuity. They have generally one large pond near the sea, into which the water flows by a channel cut through the rocks, or is carried thither by the natives in large calabashes.”

“After remaining there some time, it is conducted into a number of smaller pans about six or eight inches in depth, which are made with great care, and frequently lined with large evergreen leaves, in order to prevent absorption.”

“Along the narrow banks or partitions between the different pans, we saw a number of large evergreen leaves placed. They were tied up at each end, so as to resemble a shallow dish, and filled with sea water, in which the crystals of salt were abundant.” (Ellis, 1826)

Early export users were the Russians, who first made contact in the Islands in 1804. A year or two later, Kamehameha made known to them that he would “gladly send a ship every year with swine, salt, batatas (sweet potatoes,) and other articles of food, if (the Russians) would in exchange let him have sea-otter skins at a fair price.” The following year, they came to the islands for more salt. (Kuykendall)

Later, in the early-1820s, the Russians could get most provisions cheaper from Boston or New York than from the Hawaiian Islands, but the salt trade between the North Pacific and Hawaiʻi continued.

On September 5, 1820, Petr Ivanovich Rikord, governor of Kamchatka, wrote to Liholiho (Kamehameha II) requesting salt be traded for furs. In 1821, Captain William Sumner sailed the Thaddeus (the same ship that carried the Protestant missionaries to Hawaiʻi in 1820) from Hawaiʻi to Kamchatka with a load of salt and other supplies. (Mills) (Check out the letter from Rikord to Liholiho in the album.)

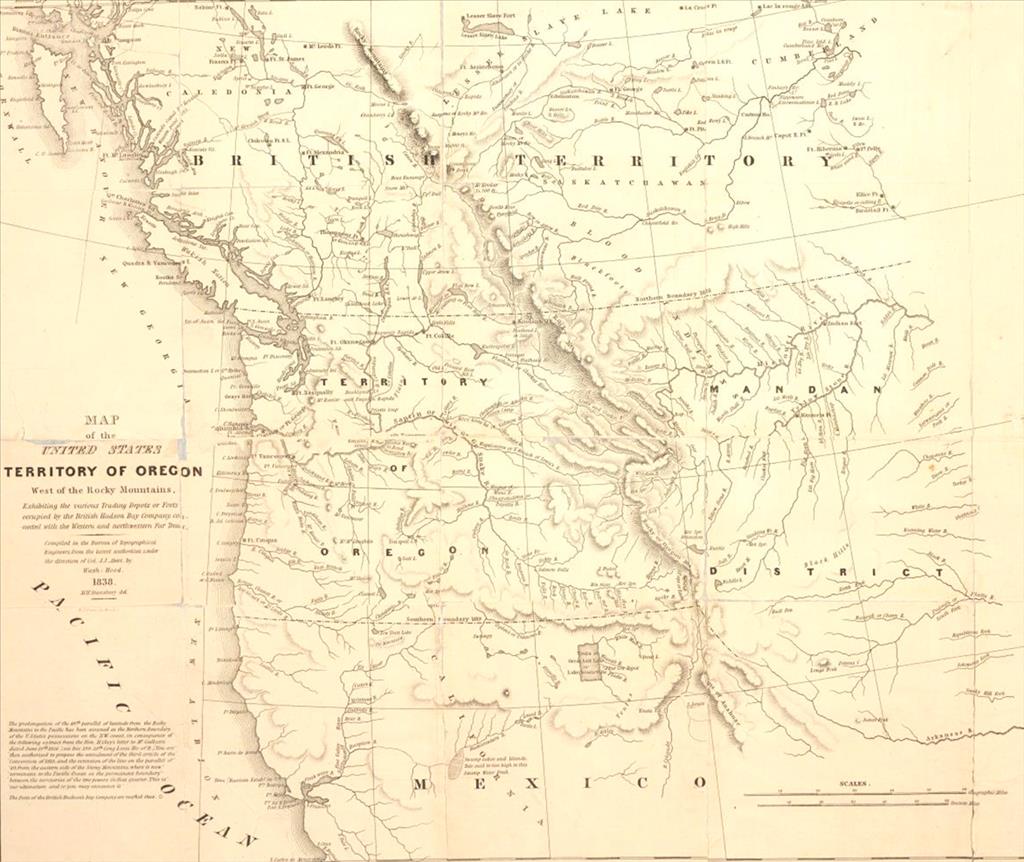

Another trading concern was the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC,) a fur trading company that started in Canada in 1670; its first century of operation found HBC firmly focused in a few forts and posts around the shores of James and Hudson Bays, Central Canada.

The Company was attracted to Hawaiʻi not for furs but as a potential market for the products of the Company’s posts in the Pacific Northwest. That first trip (1829) was intended to test the market for HBC’s primary products, salmon and lumber. (By then, Honolulu had already become a significant Pacific port of call and major provisioning station for trans-Pacific travelers.)

Back then, salmon was a one of the most valuable commercial fisheries in the world (behind the oyster and herring fisheries.) (Cobb) Just as salt was used for curing furs, HBC used Hawaiian salt in preserving salmon.

Hawaiian salt used in preserving the salmon made its way back to Hawaiʻi for Hawaiian consumption. During the 1830s, HBC sold several hundred barrels of salmon a year in Honolulu. The 1840s saw a major increase in sales; in 1846, 1,530 barrels were shipped to Hawaiʻi and HBC tried to increase salmon exports to 2,000 barrels annually. (Thus, the creation of lomi lomi salmon.)

The salt also came in handy with the region’s supplying whalers with fresh and salt beef that called to the Islands, as well as the later Gold Rushers of America. Here is where Samuel Parker (of the later Parker Ranch fame) started out as a cattle hunter to fill those needs.