by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

“Whereas, Marcus C Monsarrat, a naturalized subject of this Kingdom, is guilty of having perpetuated a grievous injury to Ourselves and to Our Royal family”.

“(We) do hereby order that the said Marcus C Monsarrat be forthwith expelled from this Kingdom; and he is hereby strictly prohibited, forever, from returning to any part of Our Dominions, under the penalty of Death.” King Kamehameha IV and Kuhina Nui Victoria Kamāmalu (May 20, 1857)

Whoa … let’s look back.

Marcus Cumming Monsarrat was born in Dublin Ireland on April 15, 1828. He is a descendant of Nicholas Monsarrat of Dublin, who went to Ireland from France in 1755.

Marcus made his home in Canada before coming to Hawaiʻi and was admitted as a member of the Law Society of Upper Canada, June 18, 1844, at Osgoode Hall, Toronto.

He came to the Islands in 1850.

He was deputy collector of customs and later entered the lumber firm of Dowsett & Co, which was eventually absorbed by SG Wilder & Co.

Marcus married Elizabeth Jane Dowsett; their children were, James Melville Monsarrat (1854-1943,) Marcus John Monsarrat (1857-1922,) Julian Monsarrat (1861-1929,) Kathleen Isabell Monsarrat (1863-1868,) William Thorne Monsarrat (1865-1924) and Samuel Archibald Monsarrat (1868-1956.)

Prince Lot had invited Marcus Monsarrat, who lived nearby, as a guest at a dinner party on January 15, 1857. Two weeks before, Monsarrat led a group of merchants in presenting a new carriage to Queen Emma on her 21st-birthday.

When dinner was over, Monsarrat bid his goodbye and left.

So far, so good – so, why the expulsion? … It’s what happened next ….

Soon after, one of Lot’s servants said the tall, handsome Monsarrat was in Victoria Kamāmalu’s bedroom. (Kanahele)

Prince Lot burst into Victoria Kamāmalu’s quarters and discovered her in compromising circumstances with his guest Marcus Monsarrat (he was ‘arranging his pantaloons.’) (KSBE)

Lot ordered him to leave and threatened to kill him. Later, the King blamed Lot for not ‘shooting Monsarrat like a dog.’ (Kanahele)

The king then “commanded (Marshal WC Parke,) in pursuance of Our Royal order, hereto annexed, forthwith to take the body of MC Monsarrat, and him safely convey on board of any vessel which may be bound from the port of Honolulu to San Francisco, in the State of California”. (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 28, 1857)

On Wednesday, May 20, Mr. Monsarrat was led to believe he would be allowed to remain in Honolulu long enough to settle up his affairs, and would for that purpose be granted his liberty on parole – this was declined. (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 27, 1857)

“At half past three o’clock, Thursday morning, Mr Monsarrat was conducted by the Marshal and Sheriff and a guard of forty soldiers to the steamer, which had her steam up and ready for sea.”

“On leaving the palace, Mr M was told that resistance on his part would be of no use, that the orders issued in regard to him were peremptory, and if any attempt to escape was made, he would have to be treated as a culprit. He assured those having charge of him that he had no idea of resisting, and would yield to the superior force placed over him.” (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 28, 1857)

Monsarrat refused to pay for his passage; whereupon Parke paid the captain $80. The King sent over $100 to be given to Monsarrat, that he might not say he was sent off without means. This he declined. (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, May 27, 1857)

The incident was embarrassing to the court because efforts were underway to arrange a marriage between Victoria Kamāmalu and Kalākaua; these plans were quickly aborted. (Kanahele)

Two years later (May 20, 1859,) the King reduced the sentence to seven years (the King “Being … moved by a feeling of deep sympathy” for the Monsarrat family.)

However, he was “strictly enjoined and prohibited from returning to any part of Our Domains, before the expiration of the period of banishment.” (Forbes) (When he later returned, the King had him arrested and banished, again. (Kanahele)

Monsarrat returned; he died in Honolulu on October 18, 1871. Some suggest Monsarrat Street near Lēʻahi (Diamond Head) is named for Monsarrat; others say it is for his son, James Melville Monsarrat, an attorney and Judge.

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

In 1765 the American Stamp Act was introduced into Parliament by Mr. Grenville; in support, Mr. Charles Townshend concluded an able speech in its support by exclaiming,

“And now will these Americans, children planted by our care, nourished by our indulgence until they are grown to a degree of strength and opulence; and protected by our arms; will they grudge to contribute their mite to relieve us from the heavy weight of that burthen which we lie under?”

On this colonel Barre rose, and, after explaining some passages in his speech, took up Mr. Townsend’s concluding words in a most spirited and inimitable manner, saying, “They planted by your care! No, your oppressions planted them in America.”

“They fled from your tyranny to a then uncultivated and inhospitable country, where they exposed themselves to almost all the hardships to which human nature is liable; and among others, to the cruelties of a savage foe, the most subtle, and I will take upon me to say, the most formidable of any people upon the face of God’s earth”.

“As soon as you began to care about them, that care was exercised in sending persons to rule them, who were, perhaps, the deputies of deputies to some members of this House, sent to spy out their liberties, to misrepresent their actions, and to prey upon them; men whose behaviour on many occasions has caused the blood of these Sons of Liberty to recoil within them …”

“And believe me,-remember I this day told you so, the same spirit of freedom which actuated that people at first will accompany them still, but prudence forbids me to explain myself further. God knows I do not at this time speak from motives of party heat; what I deliever are the genuine sentiments of my heart.

“The people, I believe, are as truly loyal as any subjects the king has; but a people jealous of their liberties, and who will vindicate them if ever they should be violated. But the subject is too delicate. I will say no more.”

“These sentiments were thrown out so entirely without premeditation , so forcibly and so firmly, and the breaking off was so beautifully abrupt, that the whole house sat a while amazed, intently looking, without answering a word.” (History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America, Gordon)

Sons of Liberty was an organization formed in the American colonies in the summer of 1765 to oppose the Stamp Act. The Sons of Liberty took their name from this speech given in the British Parliament by Isaac Barré (February 1765), in which he referred to the colonials who had opposed unjust British measures as the “sons of liberty.”

The origins of the Sons of Liberty are unclear, but some of the organization’s roots can be traced to the Loyal Nine, a secretive Boston political organization. The Loyal Nine (“Loyall Nine”), a well-organized Patriot political organization shrouded in secrecy, was formed in 1765 by nine likeminded citizens of Boston to protest the passing of the Stamp Act.

The Loyal Nine evolved into the larger group Sons of Liberty and were arguably influential in that organization.

The Boston chapter of the Sons of Liberty often met under cover of darkness beneath the “Liberty Tree,” a stately elm tree in Hanover Square (at the corner of Essex Street and Orange Street (the latter of which was renamed Washington Street)).

On the night of January 14, 1766, John Adams stepped into a tiny room in a Boston distillery to meet with a radical secret society. “Spent the Evening with the Sons of Liberty, at their own Apartment in Hanover Square, near the Tree of Liberty,” Adams wrote.

After his visit, Adams assured his diary that he heard “No plotts, no Machinations” from the Loyal Nine, just gentlemanly chat about their plans to celebrate when the Stamp Act was repealed. “I wish they mayn’t be disappointed,” Adams wrote.

On August 14, 1765, violence broke out in colonial Boston. Over the course of that day and several ensuing days, rioters attacked several buildings in the city, including the homes of colonial officials.

The protest resulted from the Stamp Act, passed by the British Parliament on March 22, which would require the colonists to pay taxes on most circulating paper items-such as pamphlets, newspapers, almanacs, playing cards, and legal and insurance documents.

The August riot, which arose largely from the agitation of this group, contributed to the eventual repeal of the Stamp Act. The Sons of Liberty claimed as members many of the later leaders of the Revolution, including Paul Revere, John Adams, and Samuel Adams.

The Sons of Liberty rallied support for colonial resistance through the use of petitions, assemblies, and propaganda, and they sometimes resorted to violence against British officials. Instrumental in preventing the enforcement of the Stamp Act, they remained an active pre-Revolutionary force against the crown. (Britannica)

For a number of years after the Stamp Act riot, the Sons of Liberty organized annual celebrations to commemorate the event.

Due to the increasing success of the Sons of Liberty, the British Parliament eased many of the duties in the colonies. However, the Parliament continued the high tax on tea, as the British Crown desperately needed money.

In 1773, the refusal to pay for British tea on behalf of the colonists fell upon deaf ears, and the East India Company’s trading ships were to enter Boston Harbor to sell the tea. However, rather than purchase the tea, on the night of December 16th, 1773 the Sons of Liberty boarded the trade ships docked in Griffin’s Wharf and threw the shipments of tea overboard in an event known as the Boston Tea Party.

Eventually, the patriotic resistance to British rule became too much to handle and revolution and war was inevitable. When lawmakers of Virginia gathered in 1775 to discuss negotiations with the British King, Sons of Liberty member, Patrick Henry exclaimed to the Second Virginia Convention “Give me liberty or give me death!”.

Thus, cementing the American stance for independence from British rule and initiating the American commitment to the Revolutionary War. (Battlefields)

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

The legend of King Arthur (Le Morte Darthur, Middle French for “the Death of Arthur” (published in 1485)) speaks of King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot and the Knights of the Round Table (and foresees “Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone is the rightwise born king of all England.”)

Many tried; many failed.

Legendary Arthur later became the king of England when he removes the fated sword from the stone. Legendary Arthur goes on to win many battles due to his military prowess and Merlin’s counsel; he then consolidates his kingdom. (The historical basis for the King Arthur legend has long been debated by scholars.)

In Hawaiʻi, a couple legends and prophecies relate to a stone, Naha Pōhaku (the Naha Stone.)

Its weight is estimated to be two and one-half tons (5,000-pounds.) The stone was originally located in the Wailua River, Kauai; it was brought to Hilo by chief Makaliʻinuikualawaiea on his double canoe and placed in front of Pinao Heiau. (NPS)

The stone was reportedly endowed with great powers and had the peculiar property of being able to determine the legitimacy of all who claimed to be of the royal blood of the Naha rank (the product of half-blood sibling unions.)

As soon as a boy of Naha stock was born, he was brought to the Naha Stone and was laid upon it – one faint cry would bring him shame. However, if the infant had the virtue of silence, he would be declared by the kahuna to be of true Naha descent, a royal prince by right and destined to become a brave and fearless soldier and a leader of his fellow men. (NPS)

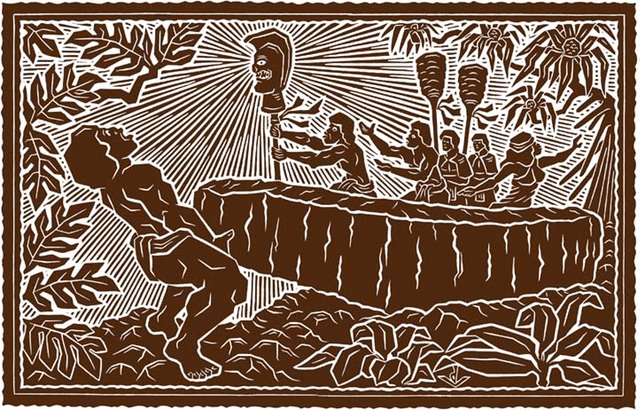

In another instance, Kamehameha traveled from Kohala to Hilo with Kalaniwahine a prophetess, who advised him that there was a deed he must do. Although not of Naha lineage, Kamehameha came to conquer the Naha Stone.

Kalaniwahine proclaimed that if he succeeded in moving Naha Pōhaku, that he would move the whole group of Islands. If he changed the foundations of Naha Pōhaku from its resting place, he would conquer the whole group and he would prosper and his people would prosper.

Kamehameha said, “He Naha oe, a he Naha hoi kou mea e neeu ai. He Niau-pio hoi wau, ao ka Niau-pio hoi o ka Wao.” (”You are a Naha, and it will be a Naha who will move you. I am a Niaupio, the Niaupio of the Forest.”)

With these words did Kamehameha put his shoulders up to the Naha Stone, and flipped it over, being this was a stone that could not be moved by five men. (Hoku o Hawaiʻi, November 1, 1927)

When Kamehameha gripped the stone and leaned over it, he leaned, great strength came into him, and he struggled yet more fiercely, so that the blood burst from his eyes and from the tips of his fingers, and the earth trembled with the might of his struggling, so that they who stood by believed that an earthquake came to his assistance. (NPS)

The stone moved and he raised it on its side.

And, the rest of the history of the Islands has been pretty clear about the fulfillment of the prophecy and unification of the Islands under Kamehameha.

The Naha Stone is in front of Hilo Public Library at 300 Waiānuenue Avenue between Ululani and Kapiʻolani Street (the larger of the two stones there.)

The upright stone sitting to the makai side of the Naha Stone is associated with the Pinao Heiau, one of several that once stood in Hilo. Some of the stones that built the first Saint Joseph church and other early stone buildings in town likely came from Pinao heiau. (Zane)

by Peter T Young Leave a Comment

Mai ka hikina a ka Ia i

Kumukahi a ka welona a ka Iā i Lehua.

From the sunrise at Kumukahi to

the fading sunlight at Lehua.

From sunrise to sunset. Kumukahi, in Puna, Hawai‘i, was called the land of the sunrise and Lehua, the land of the sunset. This saying also refers to a life span-from birth to death. (Pukui, #258)

Kumukahi is a place of importance and a place of healing. Practitioners of la‘au lapa‘au often prayed to Kumukahi and his brother Palamoa as “deities of healing” when gathering and applying traditional Hawaiian herbal medicine. These practitioners would face the Hikina (East) and chant their prayers at sunrise from where ever they were living in the islands. (Lopes)

Kumukahi is translated as the ‘beginning/first source, chief, or teacher,’ in reference to the “first source” of wisdom, knowledge or of knowing.

This is because of its location in relation to the sun, Kānehoalani (an akua who is, in one story, Pele’s father) and what the sun represents, as the easternmost point of Hawaiʻi.

It is the beginning of our collective consciousness as people of Hawaiʻi, which establishes Kumukahi as a wahi pana (living and celebrated place) and a wahi moʻolelo (a storied place). (Hawai‘i County)

Kumukahi was also noted as a “leina a ka uhane,” a place where the soul of a person would leap from this world into the next after death. (Lopes)

Kumukahi was named for a migratory hero from Kahiki (Tahiti) who stopped here and who is represented by a red stone. Two of his wives, also in the form of stones, manipulated the seasons by pushing the sun back and forth between them. One of the wives was named Ha‘eha‘e. Sun worshipers brought their sick to be healed here. (Pukui)

In some accounts, Kumukahi is a kolea bird and is referred to as “the messenger of the gods.” According to Pukui, Kumukahi was the name of a “kanaka aiwaiwa,” a divine being who loved sports, especially holua sledding.

For this reason Pele, the akua wahine of the volcano, was fond of him. Kumukahi often produced sporting events in which his people participated. Pele often joined in on these particular festivities in the form of an attractive woman.

However, on one such occasion, Pele, disguised as an old woman, requested to participate and was denied. In her anger, she chased Kumukahi to the sea where she covered him with her lava. (Lopes)

At the tip of Cape Kumukahi were a number of stone cairns, built of the rough lava from the surrounding flow, which are said to have been built by the various monarchs of the Hawaiian kingdom upon assuming the throne. Some reference them as Ki‘i Pōhaku Ali‘i – King’s Pillars.

In 1823, William Ellis and members of the ABCFM toured the island of Hawai‘i seeking out community centers in which to establish church centers for the growing Protestant mission.

Settlement patterns in Puna tend to be dispersed and without major population centers. Villages in Puna tended to be spread out over larger areas and often are inland, and away from the coast, where the soil is better for agriculture. (Escott)

This was confirmed on William Ellis’ travel around the island in the early 1800s, “Hitherto we had travelled close to the sea-shore, in order to visit the most populous villages in the districts through which we had passed.”

“But here receiving information that we should find more inhabitants a few miles inland, than nearer the sea, we thought it best to direct our course towards the mountains.” (Ellis, 1823)

Ellis noted, “The population of this part of Puna, though somewhat numerous, did not appear to possess the means of subsistence in any great variety or abundance; and we have often been surprised to find the desolate coasts more thickly inhabited than some of the fertile tracts in the interior …”

“… a circumstance we can only account for, by supposing that the facilities which the former afford for fishing, induce the natives to prefer them as places of abode; for they find that where the coast is low, the adjacent water is generally shallow.”

When the Lighthouse Board assumed control of Hawai‘i’s lighthouses in 1904, it began work on a plan to erect major lights to better mark approaches to the islands. Funds for Makapu‘u Lighthouse were secured in 1906, money for Molokai lighthouse was obtained in 1907, and Congress made an appropriation for Kilauea Point Lighthouse in 1908.

These aids to navigation were seen as “material benefit to the business .community, to shipping interests, insurance interests and mercantile interests. … [T]he next one we have recommended is for a first order light at Cape Kumukahi, the easternmost point on the Island of Hawaii.” (PCA, Nov 4, 1908)

“There is at present no landfall light for vessels bound to Hawaii by way of Cape Horn. Several vessels have within recent years gone ashore on Kumukahi Point. This is the first land sighted by vessels from the southward and eastward.”

“The shipping from these directions now merits consideration, and with the improvement of business at Hilo the necessity for a landfall light on this cape grows more urgent. It is estimated that a light at this point can be established for not exceeding $75,000, and the Board recommends that an appropriation of this amount be made therefor.” (Report of the Lighthouse Board, 1908)

On December 31, 1928, the US government purchased fifty-eight acres on Cape Kumukahi from the Hawaiian Trust Company for the sum of $500. During the following year, a thirty-two-foot wooden tower capped with an automatic acetylene gas light was built at the cape for local use. It was replaced in 1933 by a 125-foot pyramidical galvanized steel tower. (Lighthouse Friends)

“Life was peaceful for several years along the Puna coastline until a lava flow threatened Kapoho in 1955. [Kumukahi lightkeeper Joe] Pestrella stayed at his post to watch over the lighthouse as the lava advanced.”

“The following year, he received the “Civil Servant of the Year” award from the U.S. Coast Guard for his bravery in staying at his post. At the time, Ludwig Wedemeyer, leader of the Hilo Coast Guard station, noted it was the first time a Hawai‘i Island resident had received such an award from the Coast Guard.” (Laitinen)

On January 12, 1960, over 1,000 earthquakes were recorded near Kapoho Village, just above Kumukahi. The earthquakes grew in size and frequency, creating large fractures along the Kapoho Fault overnight. The 1960 Kīlauea eruption began on the night of January 13.

For the first two weeks, Kapoho village remained virtually intact except for a blanket of pumice and ash that covered everything. The lava flow issuing from the growing cinder cone was moving in the opposite direction of town.

Things changed on January 27th when very fluid lava poured from the vents and fed massive ‘a‘ā flows that moved southwestward through the streets of town. By midnight, most of Kapoho had been destroyed.

By January 28, lava destroyed Coast Guard residences near Cape Kumukahi, but the lighthouse was spared. The Koa‘e Village fell victim to lava flow progression, losing the community hall, a local church and one residence. The eruption stopped February 19. (USGS)

“After the 1960 eruption ended, an electric line was run from Kapoho Beach Lots to the lighthouse to restore power, and the light became automated. Joe was transferred to a lighthouse on O‘ahu, and when he retired in 1963, he was the last civilian lighthouse keeper in Hawai‘i.” (Laitinen)

With prevailing NW trade winds and nothing between it and the America continents, except thousands of miles of open ocean, Kumukahi has some of the cleanest air in the Northern Hemisphere.

The Kumukahi light tower is also used as a monitoring station to test air quality. Since 1993, scientists have been taking ambient air samples every week for chemical analysis.

The long-term data records supplied by these samples are fundamental to understanding changes in atmospheric composition of gases affecting stratospheric ozone, climate and air quality, and provide an avenue to detect unexpected changes in these chemicals.

The 2018 eruptions interrupted the sampling efforts and NOAA scientists have undertaken novel development of an uncrewed aircraft system (UAS) “hexacopter” that will enable the lab to not only recommence a long-standing mission that was recently forced to halt, but paves the way toward enhanced operations in the future. (NOAA)